India’s army of gold refiners face new competition

World Gold Council

World Gold CouncilMetal processing has a long story in Satish Pratap Salunke’s home.

He and his company, in the footsteps of his father and grandfather, accumulate waste gold from jewelers, melt it down, and then return it in the form of metal bars.

He operates two factories, one in Tiruchirappalli in Tamil Nadu and the other in Kochi in Kerala’s southwestern condition. In the south of India, friends have industries abroad.

He claims that “my manufacturers melt two to three pounds of silver on average every day.”

Nearly every Indian city will have at least one little factory like Mr. Salunke’s. It is known as the “unorganised” processing industry, which distinguishes it from big manufacturers who make silver pubs and coins from imported, crude gold.

A significant 25, 000 tonnes of gold are reportedly owned by American households, and some of that is usually for sale, especially when the price is high or the economy is struggling and people want to raise some money.

Although they may process returned gold on their own, they frequently employ little refiners to re-use the gold.

Local jewelers like dealing with small manufacturers like his because they work fast and are willing to take cash, according to Mr. Salunke.

Because we have offices in every city and have a few little models, the majority of jewelers choose to purchase their jewelry from us. A jeweler can return his or her delicate platinum in a few hours, unlike large refiners, who will take days to develop the recovered gold.

According to the World Gold Council, of the 900 kilograms of gold refined in India in 2023, 117 came from recycled resources.

However, India’s large commercial golden refiners are looking into that recycling industry.

They have grown in recent years thanks to favorable import duties on their primary source of crude, imported metal known as platinum doré.

However, it is challenging for them to buy enough crude gold to maintain their refineries. In fact, less than 50 % of their processing power is used, according to Harshad Ajmera, director of the Association of Gold Refiners and Mints.

But many large refiners have been setting up scrap storage facilities in large cities in an effort to turn unnecessary gold into high-quality bars.

” At present most of the recycling of gold is done by the unorganised sector ]small refiners ]- that has to change”, says Mr Ajmera.

He wants India to become a worldwide hub for gold processing, which may require more crude gold and for large companies to retake more of the metal recycling business.

The largest silver processing facility and transport hub in the world is in Switzerland. We want India likewise to be in the same place”, says Mr Ajmera.

CGR Metalloys is one of India’s leading metal manufacturers, processing about 150 kilograms of gold a month.

It has the most advanced technology for silver smelting and processing, which it claims is better for the environment and may ensure the beauty of its gold to extremely high levels, like the other big players.

” The delicate silver is analysed to the highest degrees of accuracy, on different methods of golden assaying”, says James Jose, managing chairman at CGR.

In Kerala, it has set up three metal recycling facilities.

” Indian industries have a huge capability… we have large fees. Therefore, establishing set centers will improve the circulation of broken gold. This will help increase my output by 30 % to 40 %”, says Mr Jose.

In recent years, the state has become more involved in the processing market. In 2020 the Bureau of Indian Standards ( BIS ) introduced a range of standards for gold bars including purity, weight, markings and dimensions.

Refineries that have received BIS approval may offer their bars on the commodity markets.

The industry is gradually transforming into more organization and performance, led by well-known industries that are licensed by the Bureau of Indian Standards, which are providing reliable measures for delicate silver items, making India a world hub, according to Somasundaram PR, the head of the World Gold Council India.

Mr. Salunke claims he knows his customers, but the actions taken by large recycling companies do n’t concern him much.

Local jewelers do n’t want to pay an excessive recycling fee, he claims.

And, like other smaller refiners, Mr Salunke has also been investing in modern refining technology.

They are moving away from using nitric acid to purify gold, instead switching to Aqua Regia, which is less polluting.

” The gold recycled by us is as pure as gold recycled by an organised refinery”, says Mr Salunke. It would be wrong to say that we cannot refine gold to its purest form because we now have a facility where we can test the purity.

Related Topics

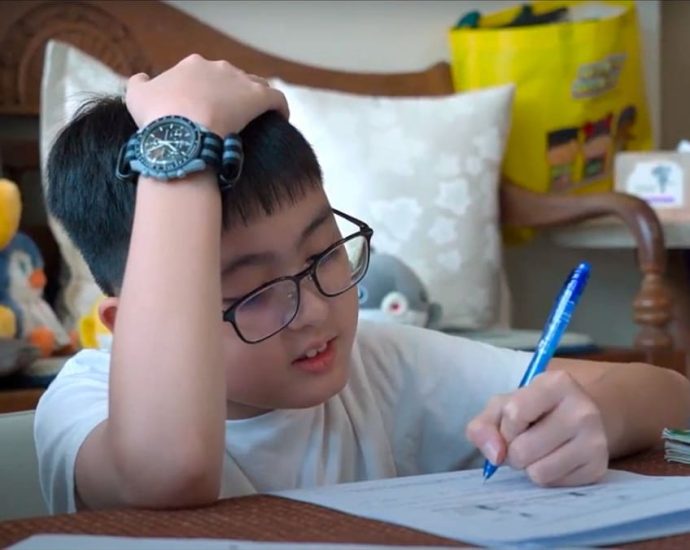

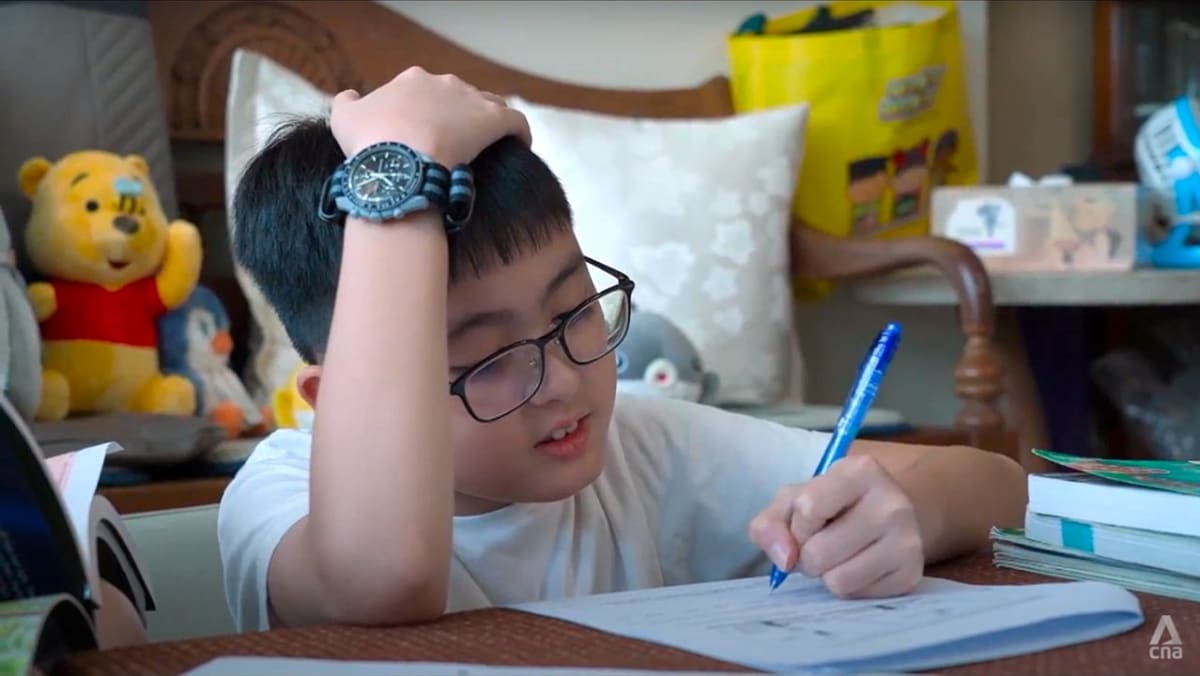

Grade expectations: Why PSLE scores matter so much to parents, pupils

However, according to a study of 1, 000 families of Main Five and Six kids, 99 per cent said great PSLE scores were important.

Since the T-score transition to Achievement Levels ( ALs ) in 2021, this is the first such nationwide survey that CNA has conducted.

In the study, 85 % of parents said their children were stressed out about the PSLE, while 64 % of parents said they were stressed out themselves.

Parents are actually “more stressed” as a result of the new scoring system, according to research professor Jayce Or, who started PSLE training seminars for parents in 2017.

What is driving the fascination with results, and what is it doing to Singapore’s kids? The program Regardless of Marks, which airs tonight ( March 29 ), examines how much has changed since recent initiatives to lessen the emphasis on academic results.

WHAT A GOOD SCORE Methods

Under the current PSLE scoring system, which spans eight ALs, the total scores range from four to 32, which are “less finely differentiated” — as intended by the Ministry of Education ( MOE ) — than the previous range of more than 200 aggregate scores.

For example, the previous grade A, which was 75 to 90 marks, is now split into AL2 ( 85 to 89 ), AL3 ( 80 to 84) and AL4 ( 75 to 79 ), with AL1 for 90 marks and above.

But in the past, children had “drop two to four scars” and still get an A, said Or, the leader of advancement heart Germinate Learning.

China’s ICBC to support stabilisation of property market

The Industrial and Commercial Bank of China ( ICBC ) announced on Thursday ( Mar 28 ) that it would support efforts being made to stabilize the second-largest economy of the world. The comments were made by Wang Jingwu, a vice president at the nation’s largest lender, at a pressContinue Reading

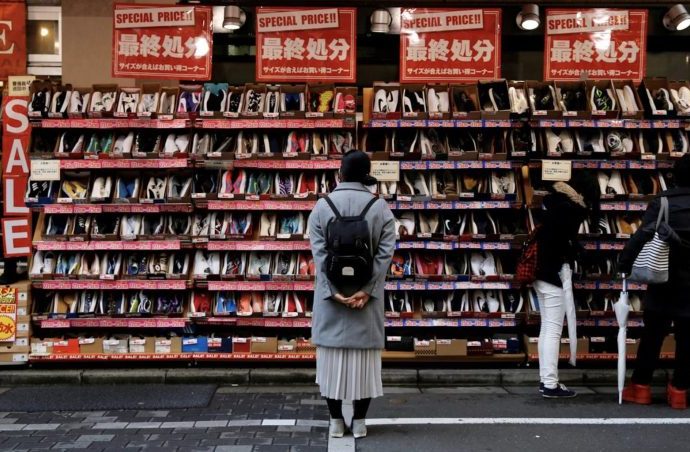

Why Japan’s big rate hike was a resounding dud – Asia Times

Japan – Central bank rate moves often get philosophical. However, investors are asking: If a price hike falls in a forest and no one is around to speak it because the world markets have ignored the Bank of Japan’s first tightening move in 17 times?

Governor Kazuo Ueda’s next thought trial, which ended 25 years of zero interest rates, was the one it was expected to trigger. It put an end to its experiment with negative yields by raising the policy benchmark from -0.1 % to 0 %.

More than skyrocketing, as some predicted, the renminbi has since weakened to 34- year highs. Alternatively of surging, 10- time Chinese bond generates are also lower today. Why do investors all over the world want to know if the BOJ’s great pivot failed in global trading markets?

The BOJ’s missed opportunity may be one reason. Businesses may have accepted the decision had then-Gouverneur Haruhiko Kuroda abandoned bad produces in late 2022 or early 2023. Buyers may have listened up if Ueda had taken the regulates immediately in April 2023.

The BOJ lost in the woods by putting off easing debate until Japan was avoiding a crisis and the US Federal Reserve was easing guesswork. Worse, it squandered yet more credibility, the only real money that counts in economic power lines.

Traders are now calling their own mountain, knowing for certain that BOJ tightening is no longer a boon for economic conditions. In part because of the decline in the yen over the past nine days, which led to the Tokyo authorities ‘ decision to act in October 2022.

Federal officials are threatening action by speaking in. Finance Minister , Shunichi Suzuki says” we are watching business movements with a great sense of urgency”. Masato Kanda, evil financing minister for foreign affairs,  , says the Ministry of Finance stands ready to pounce on extreme yen- money swings.

If Japan does intervene, strategist Shusuke Yamada at Bank of America thinks the initial purchases will start at around 2 trillion yen ( US$ 13.2 billion ) and go up to 4 trillion yen ($ 26.4 billion ).

Yamada points out that” FX treatment is a practical choice for the Japanese government to fight the yen’s failure.” ” I suspect that action, or threats to perform action, are really just a estimate of buying time until we start to see things change on a more sustained base outside the nation”.

The currency’s exchange rate is now around 151 to the money. According to HSBC’s analysts, “many seem to think a line in the sand” against more yen failure is situated close to the 152 area when treatment occurred in later 2022.”

The problem, though, is that traders clearly do n’t fear the BOJ. Not after a quarter-century of zero interest rates, 23 years of quantitative easing ( QE), eight years of negative yields, and a long, sorted history of bowing to politicians who developed a growing love for the ATM role the BOJ had assumed.

Before leaving the BOJ creating 12 months ago, Kuroda could have attained some form of semblance of authority and independence. He was the government, after all, who turned the BOJ’s easing attempts up to 11 — and then some.

The BOJ dominated the bond and stock markets under Kuroda’s view, and it was with Kuroda that the Group of Seven’s balance sheet expanded beyond the size of its$ 4.7 trillion business.

By plotting an exit, Kuroda could have saved some trust from international buyers. He demurred, passing the penny to leader Ueda in April 2023.

By slow-footing its move in the direction of some sort of leave, Ueda did the BOJ no benefits. Markets were set for a traditional BOJ pivot many times between the middle and the end of 2023. Alternatively, Team Ueda made little tweaks to friendship trading bands.

Yet those minor adjustments were lessened in the days that followed with significant, unforeseen bond payments, indicating that BOJ policy had not fundamentally changed. And that problem is now being repeated.

The BOJ made the announcement right away following the March 19 price change that waves of cash will still be flowing. According to researcher Daniela Hathorn of the trading platform Capital.com,” Ueda’s dovish comments after the meeting were enough to put an end to any post-decided bearish attitude in the Japanese currency.”

On March 27, plan committee member Naoki Tamura, a observed bird, said the “accommodative financial condition will continue”. Tamura did state that the BOJ do” slowly but surely normalize its economic policy.”

But in” BOJ time”, this may mean five times or five years. The BOJ is all wood and no bite, so why would forex investors continue to assume that?

Life things, of program. Consider the earlier standardization attempts of 2006 and 2007. The BOJ at the time ended QE and half raised formal charges. The downturn that followed enraged the democratic establishment. The BOJ after backtracked, returning to zero and restoring QE.

It follows, therefore, that the BOJ’s trust in global industry is lacking. The view is now set to see if Ueda’s team can maintain its tightening pattern even if the situation turns flimsy.

A major test is the conflicting tides complicating Japan’s 2024, including poor Chinese need.

Japan merely sluggishly avoided a recession in soon 2023. In the October-December period, the gross domestic product ( GDP ) increased by only 0.4 % year over year after contracting by 3.3 % between July and September. In January, household spending plunged , 6.3 %, the sharpest drop in 35 months.

Meanwhile, prices pressures may intensify as organisations score the biggest increase in 33 years. The 5.28 % pay knock secured during this year’s” shunto” discussions comes amid drum- tight labour markets and waning performance.

According to economist Carlos Casanova of Union Bancaire Privée,” This suggests a robust real wage growth in 2024.” Given the high inflation levels, he points out that “average regular actual cash earnings remained adverse in 2023.”

The BOJ, Cassanova says, “has been waiting for a ‘ noble cycle’ to taking hold. This is a method through which sustained, imported’ cost- drive’ inflation, fueled by Chinese yen depreciation, results in changes to business behavior, quite as rising wages and higher price- setting behavior. In turn, that can boost domestic consumption and fuel endogenous’ demand- pull’ inflation”.

Soft growth, in the context of China’s downshift, might argue in favor of no BOJ rate hikes this year. By contrast, upward wage pressures and the weakest yen since 1990 might support accelerated rate hikes.

Add in a ruling Liberal Democratic Party, which is struggling amid public outcry and economic unrest as a result of a string of political finance scandals. Fumio Kishida, the prime minister, is struggling to keep his approval ratings in the 20s ( he ended 2023 at , 17 % ).

Though the BOJ is officially independent, it’s historically not known for bucking the political establishment. With looser and looser policies, BOJ governor after governor enabled change- averse politicians. The BOJ’s largess removed the urgency for Tokyo to reform the economy and increase competitiveness.

Decades of free money took the onus off corporate chieftains to restructure, innovate or increase productivity. With China’s booming corporate welfare system still in place, the BOJ’s haven has become a harder place to revive Japan’s animal spirits.

Devising the monetary policy equivalent of a 12-step plan to deplete Japan’s excess liquidity now falls to Ueda. Step away from QE too fast and the BOJ risks setting up another 2006- 2007 episode. Move too gradually, and the BOJ loses even more street cred from international traders.

As of now, BOJ watchers are unclear on where Ueda might be headed, causing them to parse every word from the governor’s mouth and BOJ statements.

Given the current state of economic activity and prices, and for the time being, economist Takeshi Yamaguchi from Morgan Stanley MUFG says,” we need to pay attention to the expressions.” This” suggests that the future policy path would depend on changes in economic activity and prices as well as financial conditions from the perspective of sustainable and stable achievement of the 2 % price stability target,” according to Ueda.

Others predict that BOJ policy normalization will take a very long time to come into effect. ” Central banks often are compelled to make judgment calls before the desired evidence is in”, says Richard Katz, author of the new book ,” The Contest for Japan’s Economic Future”.

” Failure to decide is also a decision. But in the case of this BOJ move, there does not seem to be any such compulsion”, Katz says. ” If, when March 2026 comes and both wages and inflation fall short of the BOJ’s forecast, how will the BOJ explain its rush to tweak”?

The fact that Japan’s fortunes in 2024 depend even more heavily on Beijing and Washington than Tokyo are. The Economist Intelligence Unit doubts that China will exceed its 5 % GDP growth goal this year in a new report.

According to EIU analysts,” Consumer sentiment will remain fragile but will continue to recover gradually, supported by a rise in fiscal spending and looser monetary policy.” EIU anticipates that the government will continue to take a cautious approach to addressing pressing issues like the property sector stress and local government debt, even if this undermines market confidence.

That will cause Japan to experience feedback. The changing calculus surrounding US Fed rate cuts will change as well. Japanese officials were persuaded that Jerome Powell’s team would ease more frequently this year as the year approached 2024. Economists are quickly scaling back those forecasts because US inflation is still stubbornly high.

Viewed one way, Ueda’s team may be happy that the long- awaited shift away from QE did n’t panic world markets. However, BOJ officials should n’t be alarmed by the widening gap between perception and reality for March 19. The disconnect between yen sell orders is being expressed by traders.

It implies that the BOJ is at least perceived more as a paper tiger than as a feared authority whose sounds are heard on global markets. To raise the volume, Ueda’s team will have to act bigger and less predictably next time. The BOJ must now venture as far away from its comfort zone as rarely before.

Follow William Pesek on X, formerly Twitter, at @WilliamPesek

What would Japanese intervention to boost a weak yen look like?

WHAT HAPPENS FIRST? When Chinese authorities repeatedly state that they are” stand ready to act quickly” against speculative actions, it is a sign that intervention is on the way. Trading partners see price checking by the BOJ as a potential precursor to intervention, as evidenced by calls from central bankContinue Reading

Russian delegation visits Pyongyang to discuss cooperation against spying, KCNA says

A delegation from Russia’s External Intelligence Bureau made a trip to the North Korean capital of Pyongyang on Monday ( Mar 25 ) and Wednesday to discuss boosting cooperation against spying, according to state media KCNA on Thursday. According to KCNA, the department’s director, Sergei E. Naryshkin, and the NorthContinue Reading

Thailand moves closer to legalising same-sex unions as parliament passes landmark Bill

BANGKOK:  , Thailand’s lower house of , parliament , on Wednesday ( Mar 27 ) passed a marriage equality Bill , at the final reading, in a , landmark , step that , moves , the country  , closer , to becoming the third territory in Asia to legalise , same- sex , unions. Before it becomes law, the Bill Continue Reading

House passes landmark marriage equality bill

Thailand would only be the second country in Asia to recognize same-sex organisations.

PUBLISHED: 27 Mar 2024 at 14: 41

In its final checking on Wednesday, the House of Representatives approved a union equality bill, a historic step that will allow the nation to become the next nation in Asia to legalize same-sex unions.

Before it becomes laws, which is anticipated later this year, the costs needs approval from the Senate and aristocratic support. All major events ‘ interests were represented in the bill, and 400 of the 415 politicians present, out of which 10 voted against it, supported it.

Danuphorn Punnakanta, a Pheu Thai listing- MP and president of the political commission on the document costs, said,” We did this for all Thai people to lower gap in society and start creating equality.

” I want to ask you all to produce history”, he told other lawmakers.

The moving of the bill marks a major step towards cementing Thailand’s position as one of Asia’s most progressive societies on lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender issues, with openness and complimentary- riding attitudes coexisting with standard, traditional Buddhist values.

Thailand has long been a draw for similar- sex couples, with a lively LGBT cultural scene for locals and expatriates, and precise campaigns to get LGBT travellers.

The costs may take effect within 120 times of royal assent. Thailand would join Taiwan and Nepal as the first nations in Asia to legalize same-sex organisations.

More than a decade has passed since the bill’s creation, with difficulties brought on by political upheaval and disagreements regarding the best ways to approach it and what should be.

The Constitutional Court ruled in 2020 that the current wedding law, which merely recognises heterosexual couples, was legal, recommending policy be expanded to guarantee rights of another genders.

In the first reading, the Parliament voted in favor of four different draft bills on same-sex marriage and assigned a committee to work through them all into one draft.

The bills propose redefining the definitions of 68 Civil and Commercial Code provisions to ensure gender equality and diversity.

Thailand moves to legalise same-sex marriage

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAfter the lower apartment passed a bill granting constitutional recognition to same-sex marriage, Thailand has made a historic step closer to marriage equality.

To be laws, it also needs Senate approval and royal endorsement.

However, it is widely anticipated to occur by the end of 2024, making Thailand the sole South East Asian nation to recognize same-sex organizations.

In a region where such views are uncommon, it will strengthen Thailand’s status as a shelter for LGBTQ newlyweds.

” This is the beginning of justice. It’s not a universal solution to every concern but it’s the first step towards equality”, Danuphorn Punnakanta, an MP and president of the lower building’s committee on union justice, told congress while presenting a review of the bill. This law does not give them the right, but rather wants to return these privileges to this group of people.

The new legislation, which was passed by 400 of 415 of politicians current, will identify relationship as a collaboration between two people, instead of between a man and woman. And it will provide LGBTQ people equal rights to acquire marital tax savings, to inherit residence, and to provide medical care consent for colleagues who are incapacitated.

Thailand now has laws that ban prejudice over gender identity and sexual orientation and is, thus, seen as one of Asia’s most LGBTQ friendly governments.

However, it has taken many years of fighting to bring same-sex couples to marriage equality.

Despite widespread public support, previous efforts to legalize same-sex relationship failed. A late last year survey by the government revealed that 96.6 % of respondents were in favor of the bill.

” Yes, I’m watching the political debate and keeping my hands crossed”, says Phisit Sirihirunchai, a 35- season- old boldly gay police agent. ” I’m happy and presently anticipating that it will actually occur. I’m getting closer to having my dreams come true.

Phisit and his companion, who have been dating for more than five decades, have said they intend to get married when the new law becomes law.

Prior to the election of last year, many political parties made the promise to recognize same-sex unions in their campaigns. Sretta Thavisin, the prime minister, has also shown vigor in his aid since taking office in September of this year.

The lower house approved four bills in December to allow same-sex unions. A was proposed by Mr. Thavisin’s management, and three others by opposition parties. The lower apartment passed a bill on Wednesday that combined these into a single invoice.

Despite the high profile of transgender populations in Thailand, the Thai legislature has so far rejected proposals to change gender identities.

Thailand continues to excel in South East Asia, where same-sex connection is prohibited in some nations. It’s also an oddity in Asia.

In addition to changing its constitution, Singapore changed its constitution to prevent the courts from challenging the definition of marriage as one between a man and a woman. The colonial-era law that outlawed gay sex in 2022 was also changed.

Additional reporting by the BBC’s Thanyarat Doksone

Related Topics

Hints of a yuan versus yen currency war – Asia Times

TOKYO – The costs of a chronically weak yen only grew by US$ 18 trillion as China’s economy, Asia’s biggest, may be joining the race to the base.

It’s also unclear if the fall in the Foreign exchange rate that began Friday is the start of a trend that would undoubtedly metal international markets or simply a fluke. But the relationship with the Chinese currency’s reduction is hard to ignore.

To be sure, President Xi Jinping’s staff threw areas a lifeline on Monday. The People’s Bank of China signaled that the renminbi might not be about to fall with a somewhat higher- than- expected regular reference level of 7.0996 per dollar. That’s the biggest strengthening discrimination since November.

Even so, some analysts think the PBOC may become suddenly losing tolerance with Japan allowing the yen exchange rate to fall so far with much blowback in Washington– especially as China struggles to keep economic growth as near to its 5 % target as possible.

Chinese authorities do n’t announce weaker- than- expected daily fixing levels in a vacuum. The decision on Friday to fix the yuan rate lower as the yen was sliding anew hardly seems a coincidence.

” After Friday’s fireworks with the PBOC nudging the yuan weaker, markets have run with it”, says Sean Callow, senior currency strategist at Westpac.

Are the beggar- thy- neighbor currency strategies of the past returning to China’s$ 18 trillion economy?  ,

Economist Brad Setser, senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, speaks for many when he observes that Friday’s hint still “leaves the’ why now’ question unanswered”.

Only time will tell. Odds are, Xi and Premier Li Qiang would prefer to keep any weakening in the yuan orderly. Unleashing panic in currency circles– and in a US election year– hardly seems in Beijing’s best interest.

Already, presumptive Republican nominee Donald Trump is threatening 60 % taxes on all Chinese imports and has even suggested 100 % tariffs. US President Joe Biden, meanwhile, might engage in his own race to the bottom in a who can be more anti- China contest on the campaign trail.

Look no further than the overwhelming bipartisan support for banning ByteDance’s TikTok app on national security grounds.

In this context, says economist Robin Brooks at the Brookings Institution, Sino- US trade tensions could be seen as yuan- negative. ” You can think of a tariff as a negative” in “terms of a trade shock on a country like China. So, it’s a perfectly rational response for markets to price a stronger US dollar and weaker RMB, in this case. Market behavior is entirely in line with what theory would prescribe”.

Yet the specter of a weaker yuan could be a game- changer on a number of levels. The fallout in Washington could be considerable. Just about the only thing Biden’s Democrats and Republicans loyal to Trump agree on is tightening the screws on China.

The charged conversations at US Treasury Department headquarters alone will be a matter of breathless intrigue among analysts. Treasury Secretary Janet , Yellen , will be under growing pressure to add Xi’s government to its currency manipulation watchlist.

At the same time, Trump’s threat to revoke China’s “most favored nation” status might leave Biden’s White House feeling compelled to sign on, too. Or to go even further to limit China’s access to semiconductors and other vital technology. Tesla founder Elon Musk, for example, is practically begging for fresh tariffs on China’s electric vehicle ( EV ) makers to protect his US market.

It would put Treasury officials in a tough spot if they gave Tokyo a pass on currency depreciation, opening the US to charges of selective outrage.

Last week’s landmark Bank of Japan rate shift flopped in unexpected ways. Since March 19, when the BOJ ended its negative yield policy and raised rates to between 0 % and 0.1 %, the yen weakened 1.4 %. It’s both a sign that traders were unimpressed with the BOJ’s modest pivot and that Tokyo seems comfortable with the yen’s recent losses.

Sure, top Japanese officials are warning traders not to test their patience for a weaker yen with the exchange near 2022 intervention levels.

” The current weakening of the yen is not in line with fundamentals and is clearly driven by speculation”, Masato Kanda, vice finance minister for international affairs,  , told reporters Monday. ” We will take appropriate action against excessive fluctuations, without ruling out any options”.

Kanda added that” we are always prepared” to intervene. ” We have seen a large fluctuation of 4 % in just two weeks in the dollar- yen, a move that is n’t reflecting fundamentals and I find this unusual”, Kanda said.

Strategist Masafumi Yamamoto at Mizuho Securities thinks Kanda’s “dialed , up” warning suggests intervention might happen around the 155 level to the dollar. Goldman Sachs strategist Kamakshya Trivedi thinks 155 is a possibility as macroeconomic dynamics weigh on Japan’s economy.

Yet Japan’s soft economic performance suggests Tokyo is n’t as keen to halt the yen’s drop as its official protestations might suggest. At the close of 2023, Asia’s second- biggest economy only narrowly avoided recession.

Japan’s economy contracted 3.3 % in the July- September quarter year on year and expanded just 0.4 % in the October- December period. Household spending plunged , 6.3 % in January from a year earlier, the sharpest drop in 35 months.

” The economy is n’t in recession but it’s not far from one”, says Stefan Angrick, an economist at Moody’s Analytics. As such, he adds, “it’s hard to see the BOJ embarking on quick- fire rate hikes from here. Household and business spending are weak and inflation is falling”.

At the moment, indications are that manufacturers have “enjoyed notable and wide- ranging improvement thanks to the weak yen, with particularly marked gains in retail, wholesale, transport and utilities”, notes Masayuki Inui, an economist at Morgan Stanley MUFG.

Risks abound, of course. One is the BOJ upending the so- called yen- carry trade. Two- plus decades of zero rates and quantitative easing made Japan the globe’s top creditor nation. Since the late 1990s/early 2000s, financiers of all stripes – hedge funds, especially – routinely borrowed cheaply in , yen  , and moved that cash into higher- yielding assets everywhere.

As such, sudden , yen  , moves have a knack for shoulder- checking world markets. They often reverberate through stock, bond, commodity and real estate markets from New York to Sao Paulo to London to Mumbai to Seoul.

Given that bourses in Shanghai and Shenzhen lost around$ 7 trillion of market value from a 2021 peak to January of this year, you would think , yen- driven chaos is the last thing Asia wants.

Yet the yen’s trajectory may be giving Xi’s Communist Party geopolitical cover to engineer a more advantageous exchange rate, too. It’s become “more of an option” for the PBOC” as the economy struggles to find its footing”, notes economist Brendan McKenna at Wells Fargo Securities.

Erwan Rambourg, luxury industry analyst at HSBC, notes that the consumer demand situation in China is “proving tough”. At the same time. Beijing has made limited progress toward ending Japan’s property crisis, stabilizing local government financing or addressing record youth unemployment.

Raising China’s financial system, recalibrating growth engines and restoring confidence would be easier in a stable economic environment. These reforms and others were detailed at this month’s National People’s Congress.

As Trivium, a China consultancy, puts it:” This may all sound abstruse, but it’s critically important. Xi is asking officials to rethink fundamental aspects of how the party runs the economy. That opens the door to all sorts of changes with respect to property rights, state ownership and how resources are allocated in society. In other words, this could be big”.

As China’s cracks deepen, many investors worry that Xi’s team might not have the broadband or the audacity to shift growth engines from excess investment and smokestack industries in favor of the private sector. Or the ability to multitask to build the social safety nets needed to increase domestic demand.

Amid intensifying headwinds, no lever might reap bigger or quicker , benefits than a weaker yuan. So far, Xi’s men have avoided this option. On the one hand, it might squander progress Xi’s team has made over the last 8- 10 years to build trust in the yuan as a reserve currency alternative to the dollar.

On the other, it might give Biden and Trump common cause to intensify Washington’s trade war on the world’s biggest trading nation. A weaker exchange rate also might increase the odds that more giant Chinese property developers default in the months ahead, ala China Evergrande Group.

Asia’s paranoia about a weak yuan dates back to the 1997- 98 Asian financial crisis. Back then, devaluations in Thailand, Indonesia and South Korea caused one of modern history’s most dramatic , financial domino effects.

The resulting chaos pushed Malaysia and the Philippines to the brink. It also put Japan against the ropes. At the time, officials worried that if Beijing let the yuan drop it would trigger even bigger devaluations in Bangkok, Jakarta, Seoul and beyond.

Twenty- five- plus years later, it’s now a chronically weak yen that might give Xi all the ammunition he needs to pull the exchange rate trigger. With reason, of course. The last thing Beijing would want to be blamed for is catalyzing the next global crisis. Hence the PBOC moving today to signal its support for the status quo with a firmer daily reference rate.

But the longer Tokyo pursues a weak yen policy at a moment of increasing peril for China’s economy, the greater the odds Beijing will follow suit. Expect Beijing’s daily yuan fixing exercise to become an obsession among global investors in the days, weeks and months ahead.

Follow William Pesek on X, formerly Twitter, at @WilliamPesek