“And so we talked all night about the rest of our lives, where we’re gonna be when we turn 25”

– Vitamin C

Below, we present the two most depressing charts on China. These are the two data series most bandied about by China bears – both long-term and short-term. And ugly they do look.

In the first chart, we see that China’s births have been cut in half since 2016. Though below the replacement rate of 2.1, China’s birth rate had been running at a tolerable 1.6 to 1.8 for decades. We’ll be okay; it’s higher than Japan’s 1.3, Chinese demographers surely told themselves.

Any such confidence should have evaporated in the past five years as the birthrate plummeted to a shockingly low 1.1 (still above South Korea, said some flunky demographer).

In the second chart, China’s youth unemployment, a data series introduced in early 2018, has climbed steadily from the low teens to over 20%. It got so embarrassing that the series was “temporarily” suspended in July because “the economy and society are constantly developing and changing. Statistical work needs continuous improvement.” This proved to be even more embarrassing.

Demographics is destiny and the depressing future laid bare by annual births is surely causing aneurysms in Beijing. And then there’s the pressing emergency. Looks like the slowdown is taking an increasing toll on China’s youth with unemployment hitting 21.3% in June, the last available data point. According to these two charts, China’s future and present are melting down concurrently.

But what if? What if… what if there are different charts. Charts that address both the future and present meltdown in less fraught terms. Charts that are just as revealing but which present a different – yet related – demographic story and, perhaps, an altogether different destiny.

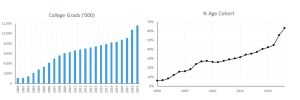

In tension with a declining birth rate has been China’s rapidly rising college enrollment. At the turn of the century, China produced one million college graduates. This represented 6% of the age cohort which we calculate by dividing graduates by births 24 years prior (the average age at college graduation is 23.7 in China). This has increased dramatically to 11.6 million graduates for the class of 2023, 63% of the age cohort.

Over this time period, college graduates in the workforce increased from low single-digit percentages to 25%. With the working-age population peaking in 2011, upgrading the labor force has become a necessity.

Happily, the investments have been made, and, barring a sudden collapse of the education system, China’s blue-collar workforce will transition to a white-collar one as retiring migrant workers are replaced by their college-educated children. College graduates in China’s workforce should exceed 70% by 2050.

Of note, over 40% of China’s college graduates are STEM majors. This compares to 18% in the US, 35% in Germany, and 26% in the OECD. Given the rapid increase in graduates, these STEM majors have taken China from a standing start to topping science and technology metrics like the Nature Index, the top 1% of cited papers, the top 10% of cited papers and WIPO PCT patents in recent years.

In real-world terms, China’s technically proficient workforce has given it the industrial output of the US and EU combined. Dozens of electric vehicle (EV) companies have emerged from nowhere with product cycles half as long as established car companies.

China has cornered the market on batteries, solar panels and wind turbines. China’s National Space Administration and defense industry have made significant technological leaps with their legions of fresh-faced engineers.

This trend should have another 20 years to run, at which point China’s workforce will have more STEM grads than the rest of the world combined. All of this is more or less written in stone until 2043. The college grads and STEM majors China’s needs by then have already been born.

The problem is what comes after the post-2017 baby bust cohort graduates from college. Without a baby bounce or – horror – continued decline, China’s future starts winding down pretty quickly.

The government has rolled out various policies designed to raise birthrates from reducing academic pressures by eliminating the tutoring industry to reducing home prices by kneecapping property speculation to promoting family time by restricting video games.

More natalist policies are sure to come. We reserve judgment on their effectiveness beyond, “We’ll believe it when we see it.”

Two anomalies strongly suggest a bounce in birth rates in the coming years. Covid’s effect on births from 2020 to 2023 should be fairly obvious. We expect a spike in births starting in late 2023 from couples who put off conceiving during the Covid crisis.

The less obvious factor is the surge in college graduates starting in 2022. This was the result of intensive investment in university expansion in the mid-2010’s. These new university spaces started enrolling students in 2018 taking an additional 1.7 million young people for the class of 2022 and 2.5 million for the class of 2023.

While we await graduation statistics for 2024 and beyond, we believe recent university expansions have enrolled an additional 3 million students per year since 2017, taking them out of both the job and family formation market until graduation. This just so happens to coincide with both the sudden decline in births and the increase in youth unemployment.

We believe family formation for the college-educated is delayed past 23.7 years of age, the average age at graduation. Educated young people often put off having children for graduate school, to establish professional careers, to play the field, to travel, to be young and hip in the city, etc. And some prolong their adolescence for so long that they entirely skip the biological imperative.

What this all boils down to is that part of the collapse in births can be attributed to delayed family formation from increasing university enrollment. While we expect many delayed births to show up in future years, they will likely come gradually with some births forever lost to Peter Pan syndrome, dating apps, gym obsession, boss girl lifestyles, and other civilization-wrecking ills of modernity.

If we had to guess, we would say China’s birthrate should partially recover to around 1.5 in five years. Any further increase will need to come from effective natalist policies which we will leave to fate and the powers that be.

The recent surge in college enrollment increased graduates from 35% of the 2017 age cohort to 63% in 2023, a 28 percentage point increase. We believe an increase of such magnitude in such a short period of time completely confounds “youth unemployment” data, which only started to be reported in 2018.

We do not know the precise methodology the National Bureau of Statistics used to calculate China’s short-lived youth unemployment, but it has been a wild ride of a continuous upward trend from 10% to over 20%, overlaid with massive seasonal swings and completely at odds with overall unemployment which has rarely stepped outside a narrow band of between 5% and 6% since 2018.

Like births, we believe youth unemployment has been upended by the surge in college enrollment. Since 2017, we calculate that employable youths (16 to 24-year-olds not in school) have fallen 43% – from 65% of the age cohort to 37% – due to increased college enrollment. We believe a proportion – say 5% – of these young people are neither employable nor educable in their youthful abandon.

These are the slackers, deadbeats, dropouts, dreamers, gaming addicts, marginally talented musicians, etc. They are not in school and contribute to the unemployment rate with their lackadaisical attitude toward finding and/or maintaining employment.

While this numerator of young slackers may remain largely constant, the denominator of employable youths has been dramatically reduced due to university enrollment of their more conscientious peers, pushing up the youth unemployment rate. We calculate that this could account for 6 percentage points of a roughly 10 percentage point increase in youth unemployment since 2018.

While highly suspicious to some, we do not doubt that “the economy and society are constantly developing and changing” and “statistical work needs continuous improvement” given the surge in college enrollment. Based on our calculations, 60% of the increase in youth unemployment since 2018 is simply a data artifact resulting from this surge.

We wonder whether much of the narrative surrounding youth unemployment is a media concoction based on a data artifact. The media, both domestic and foreign, is filled with stories of college students graduating into a hopeless job market.

While this may be true for some, or even many, it should not be a primary driver of the youth unemployment numbers given the youth cut-off age of 24 is just marginally higher than the average age at graduation of 23.7.

If new graduates are indeed unemployed at very high rates, that should drive the overall unemployment figure more than the youth figure, which does not seem to be the case.

Similarly, we wonder how much of China’s deteriorating demographic story is actually an artifact of a much more promising demographic story. A better-educated workforce was always the key to offsetting falling birthrates.

However, a sudden increase in college enrollment may have resulted in the temporary statistical illusion of collapsing birthrates.

Han Feizi is a Beijing-based financial industry veteran.