China’s market is having major issues. Despite the country’s dominance of international manufacturing, its existing criteria are starting to dwindle at a level much below that of developed countries.

China’s growth has slowed down dramatically, from around 6.5 % before the pandemic to 4.6 % now, and there are credible signs that even that number is , seriously overstated. Notice this, this, this and this on the topic. I believe that all cited here is generally in agreement.

But in the history, China has another issue that’s weighing on its people’s wealth and even making it harder to answer to the economic crisis. This is the issue of , severely lower productivity growth.

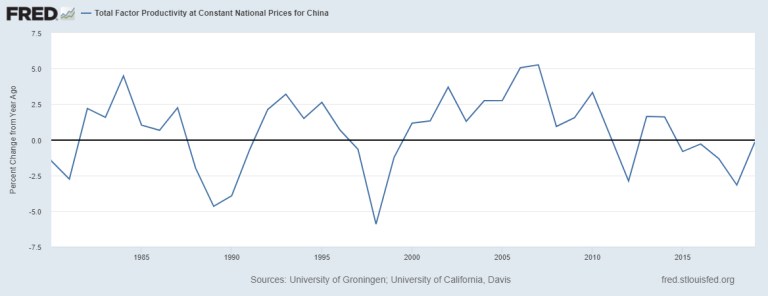

I don’t quite believe the official numbers that say China’s total factor productivity ( TFP ) has  , fallen , over the past decade and a half, but it’s undeniable that it has grown much more slowly than in previous periods.

Why? After the global financial crisis of 2008, Paul Krugman factors to a regional shift toward real house, an economy with slower productivity growth. I think that’s surely a part of the story, but perhaps not all of it.

In a post from 2022, I looked at the different possible causes of China’s productivity growth declining long before it reached rich-world living requirements.

But in light of China’s recent challenges, which have only gotten worse in the adjacent 2.5 years, I thought it might be useful to publish it today. I believe what I wrote is fairly solid.

Reading books about China’s market from before 2018 or until is always a fascinating experience. But some world-shaking events have changed the history since then — Trump’s trade conflict, Covid, Xi’s business reprisals, the real estate bust, shutdowns, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Reading predictions of China’s evolution from before these events occur is similar to reading sci-fi from 1962.

When I started , China’s Economy: What Everyone Needs to Know®, by the veteran economic consultant Arthur Kroeber, I was prepared for this surreal effect. After all, it was published in April 2016— not the most opportune timing. So I was surprised by how significant the book still felt.

Most of the book’s explanations of aspects of the Chinese economy — fiscal federalism, urbanization and real estate construction, corruption, Chinese firms ‘ position within the supply chain, etc. — are either still highly relevant, or provide important explanations of what Xi’s policies were reacting against. Dan Wang was not wrong , to recommend , that I read it.

But , China’s Economy , is still a book from 2016, and through it all runs a strain of stubborn optimism that seems a lot less justifiable six years later.

Most crucially, while Kroeber acknowledged many of China’s economic challenges — an unsustainable pace of real estate construction, low efficiency of capital, an imbalance between investment and consumption, and so on — he argued that China would eventually overcome these challenges by shifting from an , extensive growth model , based on resource mobilization to one based on greater efficiency and productivity improvements.

This was made known despite his acknowledgment of the fact that Xi’s policies so far didn’t seem to be up to the challenge of reviving it because productivity growth had already slowed well before 2016 and that he had acknowledged this.

Productivity growth is the underlying thread that has connected the Chinese economy’s entire history since 2008 in many ways. According to Basic Economic Theory, eventually the growth benefits of capital accumulation hit a halt and need to be improved to maintain growth.

Some countries, like Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan, have done this successfully and are now rich, others, like Thailand, failed to do it and are now languishing at the middle-income level. For several decades, Chinese productivity growth looked like Japan’s or Korea’s did. However, it changed slightly before Xi took office, making it appear a little more Thailand-like. Here’s a graph from , a Lowy Institute report:

In fact, the Lowy Institute’s numbers are more optimistic than some other sources. According to the Penn World Tables, China’s overall factor productivity has increased by about 0 or less since 2011.

And , the Conference Board agrees.

Personally, I suspect these sources probably , underestimate TFP growth , ( for all countries, not just for China ). However, even Lowy’s more accurate figures reveal a significant deceleration in the 2010s. If this productivity slump persists, it will be very difficult for China to grow itself out of its problems — such as its , giant mountain of debt , — in the next two decades.

Then, why has China’s productivity increased so slowly? There are several compelling reasons for Xi to make a change, and each of them has significant implications.

The first reason, of course, is that China had several tailwinds that were helping them become more productive, and these are mostly gone now.

Reason 1: Hitting natural limits

Simply put, China’s productivity increased as a result of their geographic isolation from the technological frontier. When you don’t even know how to do fairly simply industrial processes, it’s pretty easy to learn these quickly.

China imported basic foreign technology by insisting that foreign companies set up local joint ventures when they invest in China, by sending students overseas to learn in rich countries, by reverse-engineering developed-country products, by acquiring foreign companies, etc. Also by industrial espionage, of course, but there are lots of above-board ways to absorb foreign technology too.

The problem is, this has limits. The technologies you need to learn to keep growing productivity quickly increase as you get near the finish line; this is not something you can easily learn from taking classes or looking at blueprints. Companies guard these higher-level secret-sauce technologies much more carefully.

For instance, China has had trouble developing its own fighter jets because only a few companies in a few countries are aware of the metallurgy to create the specialized jet engines that enable modern top-of-the-line fighters. So it becomes necessary to start creating your own products as foreign technology becomes more and more difficult to absorb.

A second tailwind was demographics. Everyone talks about China’s unusually high demographic dividend in terms of labor input ( when there are many young people with few elders or children to care for ), but it’s also likely to be a factor in productivity.  ,

Maestas, Mullen &, Powell ( 2016 )  , shows a negative relationship between population age and productivity at the US state level, while , Ozimek, DeAntonio &, Zandi ( 2018 )  , find that the same is true at the firm level. The mechanism is unknown, but the pattern is pretty robust. In any case, China’s population reached its highest point in terms of working-age as a percentage of the total ( and quickly reached its absolute peak ) in 2010:

A third tailwind for productivity was rapid urbanization. Simply moving people from low-productivity agricultural work to high-productivity urban manufacturing work, as Arthur Lewis , is a well-known fact, increases productivity a lot. Another factor that increases productivity is agglomeration economies.

And economists believe that China reached its” Lewis turning point” right around 2010 when there was no longer any surplus agricultural laborers moving to the cities. China, of course, also unnecessarily reduced urbanization by using its hukou ( household registration ) system to prevent migrant laborers from settling permanently in cities. However, in any case, this tailwind also appears to be over.

Three significant tailwinds that were causing China’s productivity growth over the past ten years have probably dried up. And Xi Jinping or any other leader has no real authority over that. However, there are probably other factors that could be more helpful for policy adjustments that are dragging China’s productivity growth down as well.

Reason 2: Low research productivity

One thing you can do is to invent your own if you are unable to import foreign technology any longer. In fact, this is a good thing to do even if you , do  , import foreign technology, since companies should create new products and new markets instead of just aping foreign stuff. In fact, China has been investing a lot more in research and development in recent years. Here’s a chart , from the blog Bruegel:

Unfortunately, research , input , doesn’t always lead to research , output. A , 2018 study by Zhang, Zhang &, Zhao , finds that Chinese state-owned companies have much lower R&, D productivity than Chinese private companies, which in turn have much lower productivity than foreign-owned companies. And , a 2021 paper by König et al.  , finds that while R&, D spending by Chinese companies does appear to raise TFP growth, the effect is quite modest:

In other words, a lot of this spending is being done by state-owned companies that are just throwing money at “research” because the government tells them to, but not really discovering much. The authors point to the misallocation of resources as a major contributor to low R&, D productivity. They also point out that some businesses simply reclassify regular investment as” R&, D” to profit from tax breaks ( note that this is done everywhere ).

What about university research? This is a crucial component of how the US maintains its technological edge. And China has indeed been throwing huge amounts of money at university research, such that its expenditure , now nearly rivals that of the US , China recently passed the US in terms of , published scientific papers, including , highly cited papers.

However, the quality of this study has been questioned. Despite all this publication activity and all this money, Chinese universities are frequently found to be not the leaders in most areas of research.

Basically, the story is that Chinese scientists are under tremendous pressure to publish a ton of crappy papers, which all cite each other, raising citation counts. In the words of Scientific American, this has led to” the proliferation of research malpractice, including plagiarism, nepotism, misrepresentation and falsification of records, bribery, conspiracy and collusion”.

Therefore, the low productivity of Chinese R&, D may contribute to the reason why domestic innovation hasn’t surpassed foreign technology absorption.

Reason 3: Limited export markets

I’m a big fan of the development theories of Joe Studwell and Ha-Joon Chang, as everyone who reads this blog will be aware of. A pillar of the Chang-Studwell model is the idea of “export discipline“.

Basically, when companies venture out into global markets, they encounter tougher competition and also ideas for new products, new customers, and new technologies. This raises their incentive ( and their ability ) to import more foreign technology, and in general makes them more productive and innovative.

After the global financial crisis of 2008 and the recession that followed, the US wasn’t able to absorb an ever-expanding amount of imports from China. So Chinese exports to the US market , slowed in the 2010s, and then Trump’s trade war slowed them even more. China’s exports to the EU , rose a bit, but not that much.

Developed-country markets simply became saturated with Chinese goods, and there wasn’t much more room for expansion. Although developing nations are reportedly purchasing more Chinese goods, they lack the purchasing power of the wealthy nations. Since the mid-2000s, China’s exports as a percentage of GDP have actually decreased significantly:

Many people ( including Kroeber ) talk about this as a shift from export-led growth to growth led by domestic investment. And so it is. But if productivity benefits from exporting, then this is also a challenge for long-term growth, because there’s less opportunity for export discipline to work its magic.

This may be one factor in the decline in growth for large nations compared to smaller ones. When you have 1.4 billion people, than when you only have 50 million, as South Korea does, because the world is suffocated with your exports, which is much harder to be an export-led economy.

Which raises the question of why the US is so productive, even more productive than the majority of the rich and productive East Asian nations. Consumption might have a role in that.

Reason 4: Not enough consumption

The US has a very large economy that is geographically dispersed from the majority of the world’s major economies. This explains why the US has a very low , amount of trade relative to GDP , — just 23 %, compared to 81 % for Germany and 69 % for South Korea.

However, the US has a highly productive economy, surpassing that of all but a few small wealthy nations. Exports undoubtedly contributed to the US’s expansion, but in large part it was just selling itself.

As the chart above shows, China increasingly does the same. But unlike the US, China’s domestic economy is heavily weighted towards , investment in capital goods  , — apartment buildings, highways, trains, and so on. China’s final consumption is , only 54 % of GDP, compared to over 80 % in the US.

And private household consumption accounts for , only 39 % of China’s GDP, compared with 67 % in the US. China is undoubtedly in a later stage of development, but Kroeber points out in his book that even nations like Japan and South Korea had significantly higher consumption shares at comparable stages of their own growth stories.

Usually this gets discussed in the context of “imbalances”. But what if it also affects productivity? Consumers have a preference for differentiated goods that spurs companies to develop new products, increase quality, offer new features, and so on.

The strategy professor , Michael Porter argues , that when companies compete by differentiating their products instead of simply competing on costs, it results in higher value-added — in other words, it makes them more productive.

Over the past decade, China has been building a lot of buildings and a lot of infrastructure. But it hasn’t been developing a lot of innovative and high-quality cutting-edge consumer products. Unintentionally, various government initiatives that divert resources from domestic investment to domestic consumption may be reducing Chinese productivity.

And the biggest such policy might be macroeconomic stabilization.

Reason 5: Macroeconomic stabilization

It’s important to stabilize the economy. Recessions cause many people to lose their jobs and cause a lot of suffering, and they most likely also cause underinvestment in businesses. They can damage the cohesion of entire societies. In 2008-11, the US learned this lesson the hard way when our insufficient fiscal stimulus caused a recession that was longer and more painful than it had to be.

But there may be such a thing as too much stabilization. As , I explained in a post last September, China avoided going into recession both in 2008-11 and again in 2015-16 ( after a big stock market crash ) by pumping money into real estate, via , lending by state-controlled banks,  , often to SOEs , and to , local governments.

This likely prevented the Chinese economy from experiencing recessions in 2008, 2008, and 2015-16. But it had a big negative effect on productivity growth, for three reasons.

First, SOEs simply aren’t very productive compared to other Chinese companies. Second, the funds were quickly thrown out the window, leaving little time or motivation to determine which projects were worthwhile.

Third, construction and real estate are two key sectors of the economy that have a reputation for having low rates of productivity growth. This last is probably the scariest, as it led China’s economy to be , more dependent on real estate , than any other in recent memory:

Anyone who has followed , the saga of China’s Covid lockdowns , will sense a familiar pattern here. The Chinese government, eager to preserve the appearance of invincibility, often goes overboard in unleashing the tools of control.

Although recessions are not good things, the measures taken by Chinese policymakers to make sure they never had even the slightest recession may have left their economy with a significant hangover from the low-productivity sector.

Will Xi bring back the increase in productivity?

There are many reasons why China’s productivity growth fell to a low level in the 2010s and 2020s.

But speeding it back up again — which every analyst, including Kroeber, seems to recommend — will be no easy task. The negative effects of productivity have vanished. These systems have a way of becoming established, and China’s misallocation of resources toward low-quality research and low-quality real estate industries won’t be easy to reverse.

Xi Jinping, of course, is going to try. Part of his effort consists of , industrial policy , — the , Made in China 2025 , initiative and the , big push for a domestic semiconductor industry. Whether those will bear fruit is still to be seen.

But in the last three years, Xi has undertaken a second, more destructive effort to reshape China’s industrial landscape. He has attacked the industries he doesn’t want, rather than simply boosting the industries he wants.  ,

He has cracked down , on consumer internet companies, finance companies, video games and entertainment. And he has attempted to , curtail the size of the real estate industry, resulting in a slow-motion crash that ‘s , still ongoing.

Essentially, Xi is trying to crush industries he doesn’t like, in the hopes that resources — talent and capital — flow to the industries he does like. This is a new kind of industrial policy — instead of “picking winners”, Xi is stomping losers.

One of the saddest things about optimistic 2016-era analyses like Kroeber’s is how much hope they place in internet companies like Alibaba, Tencent, and Baidu as heralds of a new, more innovative China. Xi has declared that these companies are not, in fact, the future.

However, it’s not at all clear that an economy operates similarly to a tube of toothpaste when resources are squirted out from one end. Do you really believe that starting a semiconductor company rather than an internet company will help you become Emperor Xi’s favor as a budding entrepreneur?

What if he decides next week that he doesn’t need more chip companies and that your business isn’t one of his preferred champions? What if after you get rich and successful, Xi decides you’re a potential rival and appropriates your fortune?

An economy with a leader who consistently destroys businesses and industries he dislikes is inherently risky. Chinese engineers and managers will, indeed, follow Xi’s orders and work in the sectors he wants them to. However, the absence of entrepreneurial spirit and initiative may result in this being a pyrrhic triumph.

In other words, escaping China’s low-productivity-growth trap is going to be tough, and Xi’s strategy doesn’t fill me with a ton of confidence so far.

This , article , was first published on Noah Smith’s Noahpinion , Substack and is republished with kind permission. Become a Noahopinion , subscriber , here.