Analysts at Fitch Ratings aren’t looking out for China as they tiptoe up to downgrading Washington’s AAA credit rating. But written between the lines in bold font is how a US default would give Beijing the big trade war win Xi Jinping has been seeking.

To be sure, China won’t love the paper losses on its stockpile of US$870 billion of US Treasury securities. Nor will Chinese leader Xi or Premier Li Qiang welcome the ways in which surging US debt yields make China’s 5% growth target less attainable.

But the immediate devastating blow to US leadership and credibility from a default would play right into Xi’s goal of increasing the yuan’s role in finance and trade — and thus giving China a bigger say in global economic affairs.

And yet, it’s not quite that simple. Just as US Congress members play games with the debt ceiling and teeter towards default, Chinese stocks are cratering.

The CSI index has erased all its gains for the year so far as China’s post-Covid recovery disappoints. It’s hard not to wonder if the common link here isn’t the trade war that neither side seems ready to end.

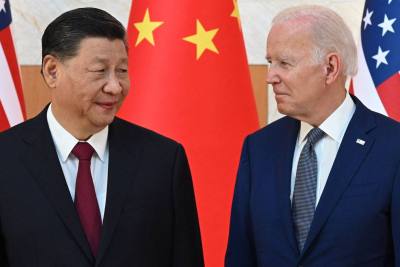

Call it mutually assured economic destruction. In the 855 days of the Joe Biden presidency, his White House continued predecessor Donald Trump’s punitive tariffs against China.

In many ways, Biden has gone after China with even greater verve. Biden is not doing it with blunt taxes and angry tweets, but surgical and steady efforts to deprive China of access to vital technology.

China, of course, has retaliated in kind. But as the two biggest economies face intensifying headwinds, it’s high time US and Chinese officials lowered the temperature and found a way to stop the insanity, many analysts believe.

A widely watched meeting in Vienna earlier this month between US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan and China’s top diplomat Wang Yi generated some muted optimism. Both sides described the discussions as “candid, substantive and constructive.”

Another chance to return to normalcy will come at a dinner planned for May 25 in Washington, where US Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo will dine with her Chinese counterpart Wang Wentao, marking the first cabinet-level meeting in Washington between the two sides during the Biden administration.

Yet where Biden or Xi stands on the it’s-time-to-talk continuum is anyone’s guess.

It’s time to admit the ongoing “decoupling” drama between the US and China is having an “adverse effect” on the companies of both nations, saysErgys Islamaj, senior economist at the World Bank.

What’s more, Islamaj notes, “the fragmentation of standards, especially between the world’s two largest markets, can not only constitute additional barriers to trade and investment between the two countries.”

The “fragmentation,” he says, “creates additional burdens and diseconomies on exporters and multinational corporations from third countries, as companies need to adjust their products and processes to comply with different regulations.”

All this is creating “additional costs and complexity in sourcing decisions” and it’s not a formula for innovation or economic confidence, Islamaj concludes.

Wang Qi, CEO of MegaTrust Investment, thinks ending what he calls an all-out “investment war” will be hard. As he puts it: “Trump started the trade war. Biden initiated the tech war. Yet they both wanted an investment war with China.”

Worries about heightened US-China tensions have weighed on Chinese stocks since late April. This is just months after the US Public Company Accounting Oversight Board completed its first round of audit inspections on Chinese ADRs, or American depositary receipts, “which reduced the delisting risk,” Wang says.

For now, at least. Many, though, “seriously underestimated the gravity of the so-called investment war, which is still on today,” Wang says. “Trying to limit Chinese companies’ growth by trade or tech sanctions is one thing. Putting an explicit cap on the US investments in Chinese stocks is another. The latter is arguably more direct and detrimental to the share price.”

US officers can, and do, make reciprocal claims about Beijing. Yet neither economy is thriving in this environment. US growth cooled in the first quarter. Gross domestic product (GDP) rose at an annual rate of 1.1% in the January to March period, down from 2.6% in the previous quarter last year.

“Compared to the fourth quarter, the deceleration in real GDP in the first quarter primarily reflected a downturn in private inventory investment and a slowdown in nonresidential fixed investment,” the US Commerce Department said earlier this month.

To Fitch economist Olu Sonola, the downshift is not a fluke. Despite unemployment sitting at a 54-year low, Sonola notes, US labor markets will weaken as aggregate demand stagnates in response to higher interest rates and tightening credit conditions, exacerbated by stress in the banking sector.

“Labor demand still exceeds supply, but this imbalance is declining, now at approximately 2.3% of the labor force in first quarter 2023 compared with 3.2% last quarter,” Sonola says. “Job openings have also declined by 1.6 million from peak levels. Wage growth year-over-year has decelerated significantly since last quarter in a number of states.”

Clearly, trade headwinds aren’t doing China any favors either. Retail sales, industrial output and fixed investment expanded much less than hoped in April. The youth unemployment rate hit a record high of 20.4%, raising concerns for social stability.

Economist Jeffrey Currie at Goldman Sachs says deep concerns over the health of the global financial sector, US debt ceiling risks, fears of an impending demand slowdown in the West and a disappointing recovery in China in April have all contributed to “fears of an upcoming US or global recession.”

Those fears will be turned up to 11 or higher as the US flirts with default. Enter Fitch, with a perilously timed downgrade warning as US politicians play with fire. It moved the US to “rating watch negative” the “X-date” when Washington runs out of cash.

In its statement, Fitch said “we believe risks have risen that the debt limit will not be raised or suspended before the X-date and consequently that the government could begin to miss payments on some of its obligations. Prioritization of debt securities over other due payments after the X-date would avoid a default.”

Adding to the uncertainty is where Biden and Xi might take their economic clash next.

Some think Team Biden should be careful what it wishes for. Economist Michael Beckley at the Washington-based Wilson Center says that “most debates on US-China policy focus on the dangers of a rising, confident China. But the United States actually faces a more volatile threat: an insecure China mired in a protracted economic slowdown.”

Chinese growth, he adds, has fallen by half over the past decade and is “likely to plunge in the years ahead as massive debt, foreign protectionism, resource depletion and rapid aging take their toll. Past rising powers that suffered such slowdowns became more repressive at home and aggressive abroad as they struggled to revive their economies and maintain domestic stability and international influence. China already seems to be headed down this ugly path.”

The bottom line, Beckley concludes, is that “slowing growth makes China a less competitive long-term rival to the United States, but a more explosive near-term threat. As US policymakers determine how to counter China’s repression and aggression, they should recognize that economic insecurity has spurred great power expansion in the past and is driving China’s belligerence today.”

Clearly, China could make a similar argument about the specter of Trump getting a second shot at power after the November 2024 election. Trump, after all, recently reiterated he favors a US default.

But if the definition of insanity, as Albert Einstein said, is trying the same play over and over expecting a different result, then there’s still too much crazy in US-China relations.

Follow William Pesek on Twitter at @WilliamPesek