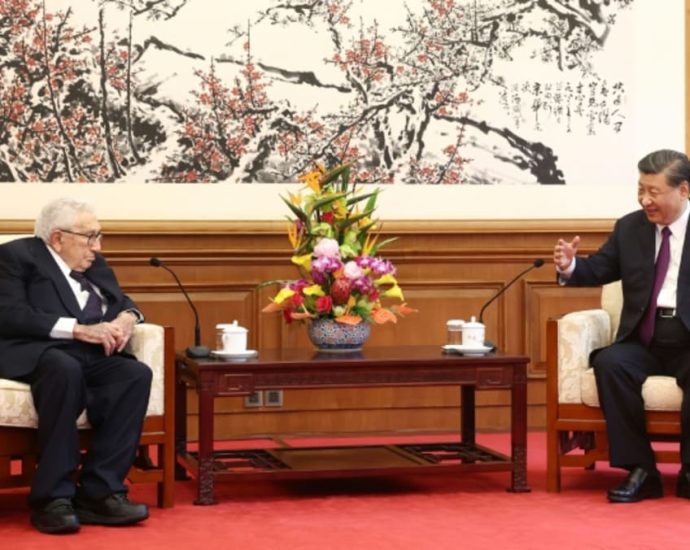

Commentary: How will Henry Kissinger be remembered in Southeast Asia?

HENRY KISSINGER’S WORLDVIEW

In trying to understand the enigma of the man, we have to understand his worldview. Dr Kissinger was the ultimate practitioner of realpolitik pragmatism. For him, morality had little place in the arena of world politics where power served as its prime currency.

If anything, excessive preoccupation with moral arguments were a distraction from – if not an obstacle to – the larger objective of peace, which to him was ultimately about avoiding the kind of great power conflagration that brought about World War II. To achieve this objective, difficult decisions would have to be made which, to Dr Kissinger, left little room for sentimentality.

This leads to a second point: To Dr Kissinger, the chief actors in the script of global politics were the great powers. Throughout his time in office during the terms of US presidents Richard M Nixon and Gerald R Ford, Dr Kissinger was consumed by Cold War competition with the Soviet Union and principally, the question of how to prevent a major nuclear conflict without compromising American interests and security.

It is from this prism that some of the US’ most controversial policies during those years, many attributed to him and that have tainted his legacy, should be viewed, such as the toleration of right-wing dictatorships in Latin America, complicity in violence in Bangladesh and the bombing of Cambodia.

KISSINGER’s IMPACT ON SOUTHEAST ASIA

With these aspects of Dr Kissinger’s worldview in mind, what were his contributions and connections to Southeast Asia? After all, if indeed his preoccupation was with great power politics, how did he view a region that comprised small and medium-sized states?

As national security adviser and later also secretary of state to US presidents Nixon and Ford, Henry Kissinger served during the most turbulent years of recent Southeast Asian history, when Soviet and Chinese-supported communist movements threatened to take over many governments in the region.

While communist insurgencies raged across Southeast Asia, it was in Vietnam where the threat was most urgent. Indeed, as early on as the presidency of Dwight D Eisenhower, the US was already seized by the prospect that the fall of Indochina to communism would allow the ideology to spread across Southeast Asia. This became known as the “domino theory”.

Dr Kissinger was instrumental in crafting and executing American policy at the height of the Vietnam War. He would oversee further escalation of the war, both in terms of the number of US troops deployed and also the expansion of the war to Cambodia, which he thought necessary in order to weaken the Vietcong.

Nevertheless, the ballooning cost of the war, mounting American casualties, and President Nixon’s promise to scale down US involvement, compelled Dr Kissinger to pursue secret negotiations with North Vietnam for the US’ eventual withdrawal.

Both he and his North Vietnamese counterpart, Le Duc Tho, were awarded the 1973 Nobel peace prize for their efforts. Mr Tho declined it, and Dr Kissinger never went to Oslo to collect his for fear of widespread protests given how unpopular the war had become.