Citi appoints new Malaysia CEO

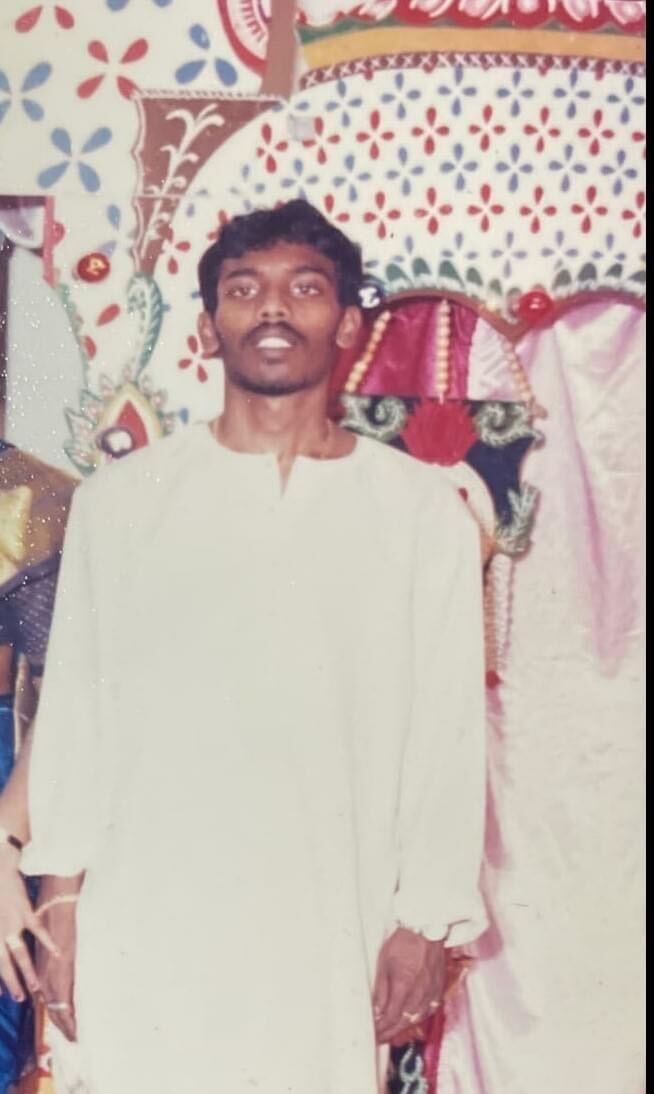

Citi has appointed Vikram Singh as new CEO of its Malaysian business, effective from May.

A spokesperson for the bank told FinanceAsia that Singh had already relocated to Kuala Lumpur for the new role, which will see him prioritise growth across the market franchise.

In his new capacity, Singh reports to Amol Gupte, head of South Asia and the Asean region, and takes responsibility for the full suite of the bank’s activities in Malaysia. This includes oversight of the performance of Citi’s Solutions Centres in Kuala Lumpur and Penang, which support its wider banking operations in over fifty countries.

Singh has served across a number of Citi’s core divisions to date. He started his career with the bank 24 years ago working across its India-based business, in posts located in Mumbai, Bengaluru and New Delhi. Most recently, he was head of Asia Pacific Regional Account Management, managing coverage of global subsidiary clients operating in the region, from Singapore.

A release shared with media pointed to Singh’s particular expertise leading the bank’s Corporate and Investment Banking effort in the Philippines over a period of five years, during which he devised robust business strategies that went on to achieve double-digit revenue growth.

“Vikram’s long career and experience with the firm will be invaluable in leading the next stage of growth in a market that also supports many of our global businesses and functions,” Gupte said in the announcement.

Citi established a presence in Malaysia 64 years ago. In January 2022, the bank announced plans to sell its consumer franchise in four Asean markets including Malaysia, to United Overseas Bank (UOB). The deal finalised in November 2022, bringing the bank regulatory capital benefits of approximately $1 billion.

Offering an update on the bank’s performance in the market following the divestiture, the spokesperson told FA, “We continue to see good client activity across our institutional businesses.” He noted “good growth and client work”.

Elaborating on the current opportunities that Malaysia presents, the contact pointed to varied growth avenues across investment and corporate banking, as well as within the bank’s trade and treasury business, such as hedging.

“Across our institutional businesses from Banking, Markets and Services, we see opportunities to support both local and multinational corporate (MNC) clients further.”

The spokesperson added that the bank has recruitment plans around Singh’s appointment to support client-led growth.

¬ Haymarket Media Limited. All rights reserved.