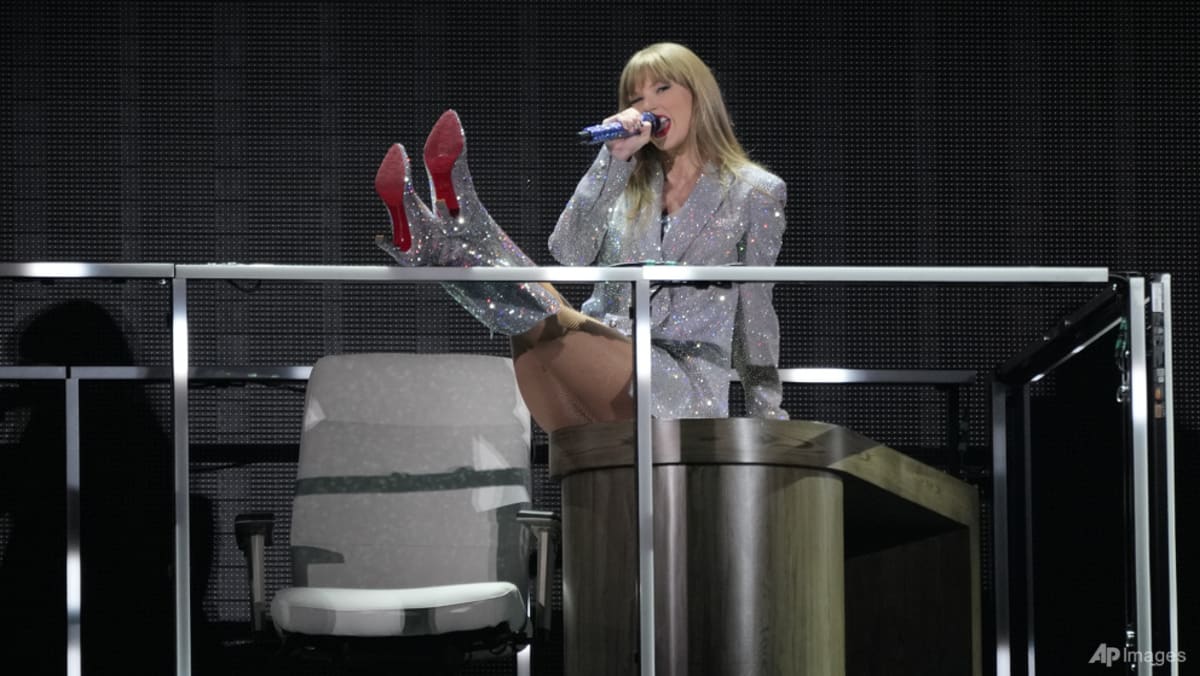

Ticket prices for Taylor Swift’s Singapore shows announced, VIP packages reach up to S$1,228

As Swifties in Singapore (nay, Southeast Asia) prepare for the great war happening next Friday (Jul 7) when general sales for Taylor Swift’s Singapore concerts go live, Ticketmaster Singapore has revealed the prices of Swift’s shows here.

There will be six categories for standard tickets, with the cheapest going at S$108 and the most expensive one going at S$348. However, hold on to your horses before you start transferring money to your newly opened UOB bank account.

Swift’s concerts will also have VIP packages which start from S$328. The six packages have mostly similar inclusions, with the exception of the seat you’ll get for the concert.

The cheapest VIP package, We Never Go Out Of Style, will comprise:

- One Cat 5 reserved seated ticket

- A set of four Taylor Swift prints

- A commemorative VIP tote bag

- A Taylor Swift pin

- A Taylor Swift sticker & postcard set

- A souvenir concert ticket

- A special VIP laminate & matching lanyard

If you’re going all out, consider getting the most expensive It’s Been A Long Time Coming VIP package (S$1,228) which gives you a reserved seat on the floor.

Taylor Swift will be performing in Singapore (the only Southeast Asian stop) for six nights in March 2024.