Gaza tragedy a reminder that Hindutva is a major barrier to IMEC

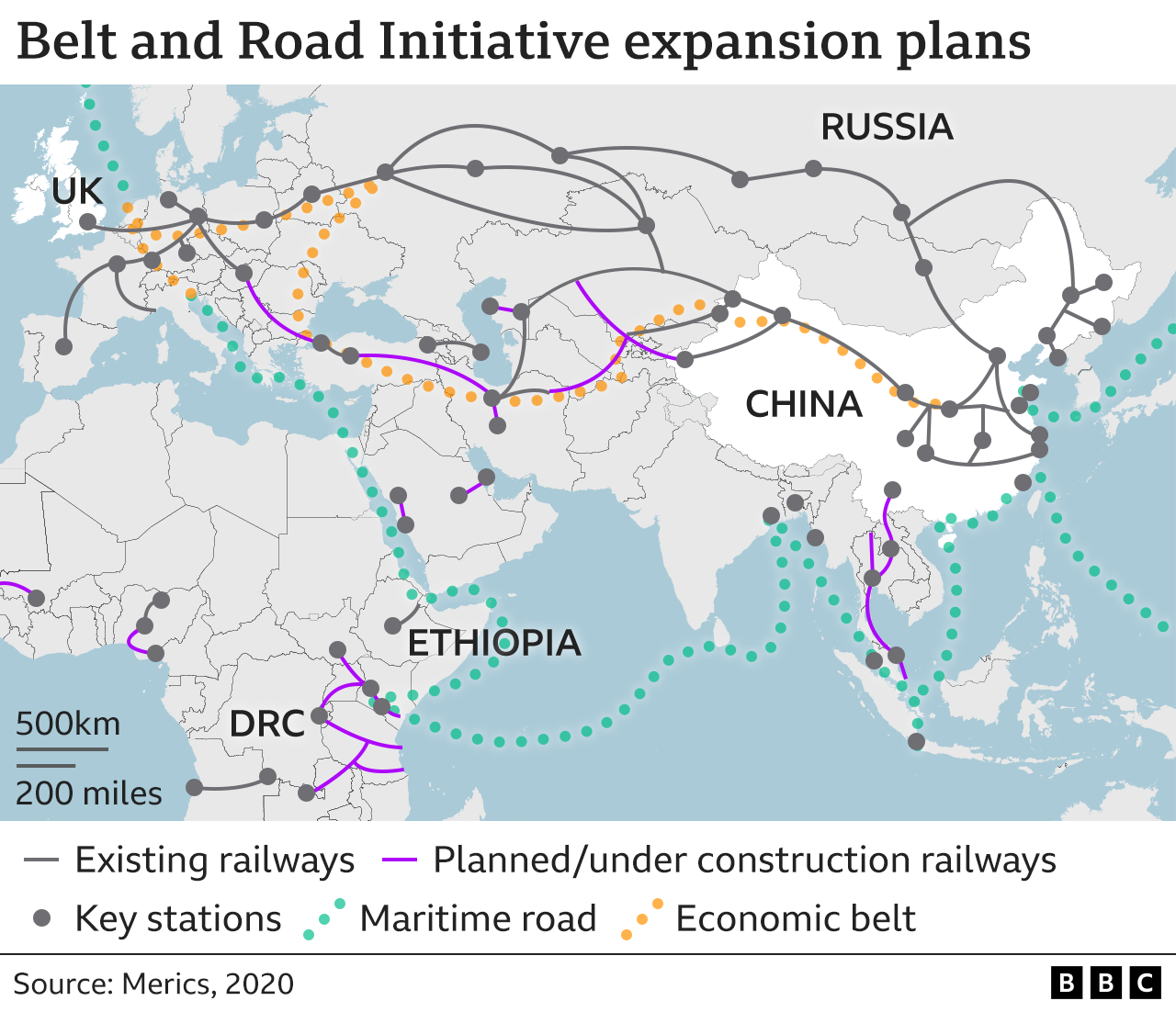

A new economic hall was inaugurated on the outside of the 18th G20 Summit, which was held in New Delhi under the presidency of India. It is a significant trade and investment project known as the India, Middle East, and Europe Economic Corridor( IMEC ).

It departs from India and travels through Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and the Persian Gulf of the Middle East before arriving in Europe via Greek slots.

The Middle East and Europe will be connected by broad territory and maritime transportation thanks to two distinct corridors, according to IMEC. Although many of its specifics are still pending and it is currently only in the form of a memorandum of understanding( MoU ), its estimated cost is US$ 20 billion.

The future of IMEC, but, appears uncertain now that a human tragedy is taking place in Gaza.

India’s preference for Israel

In stark contrast to the history, India this moment sided with Israel and abandoned its previous stance on Palestine. Prime Minister Narendra Modi decided to support Israel shortly after the Palestine-Israel issue erupted, tweeting,” India stands with Israel.”

Later, he spoke with Benjamin Netanyahu, his Israeli rival, and denounced all forms of terrorism. As the prime minister opted to support Israel firmly rather than align his declaration with the two-state solution, this signaled a distinct change from India’s prior stance on the Palestine-Israel discord.

Additionally, he did not denounce Israel’s continued murder of Palestinians. He also did not criticize Israel for the significant civilian casualties in a Arab hospital.

Arindam Bagchi, a spokesperson for the Indian Ministry of External Affairs( MEA ), reaffirmed India’s previous stance, saying that it” believes in its long-standing support in the establishment of an independent, sovereign, and viable state of Palestine.”

The paradox through which India is interacting with the Middle East can be seen in the statements and quick response of the country’s prime minister and the Foreign Affairs Ministry. Pragmatically, India’s growing economic and geopolitical dependence on Israel can be used to explain this change in international policy. That nation is an important trading partner of India, receiving$ 3.94 billion in US imports each year.

turbulence in the Middle East

Without harmony, there can be no financial growth. The IMEC and its successful application in a disturbed area like the Middle East are examples of this. As a result, the continued human tragedy in Gaza has an impact on bilateral trade between Israel and India in addition to casting doubt on the IMEC’s leads.

Anjana Pasricha, a reporter for Voice of America in New Delhi, described the Israel-Hamas conflict as” reality check” and” wake-up call” for IMEC.

Michael Kugleman, the chairman of the South Asia Institute at the Wilson Center in Washington, emphasized that IMEC was not feasible in the unstable Middle East. He said that IMEC” is hardly just a matter of funding challenges, but also of balance and political cooperation.” & nbsp,

Again, it is clear that IMEC cannot be implemented in the Middle East as long as India just supports one position.

A large portion of this financial action was dependent on the long-running normalization of Israel and Saudi Arabia. The US-led Abraham Accord 2.0 is also in disarray following the Israel-Hamas issue.

Manoj Joshi made a remark about this at the Observer Research Foundation, saying that IMEC was started under the assumption that the Middle East was at serenity.

Other than that, IMEC stokes long-standing competitions between Ankara and Athens by avoiding Turkey. India is undoubtedly treading a fine line as it comes across the region’s long-standing conflicts.

Is India overcome the obstacles preventing IMEC and deliver on its financial initiatives in the Middle East? is a pertinent question that is related to this.

Hindutva, a challenge or an answer?

The political beliefs of a state contains the answer to this question. Since the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party( BJP ) came to power, Hindutva, its religio-political philosophy, has infused every endeavor in India, whether it be national or international.

The Modi-led Indian government describes itself as a” spiritual politics.” It claims to be a supporter of the Global South. It aims to promote changes in the world order based on naturalism and democracy while adhering to the old religious origins.

In the current Gaza tragedy, such noble claims should ideally be met with unambiguous support for mankind. Funnily, while, India refused to support a UN resolution calling for an end to the war in Gaza for the first time in its history.

The Modi administration was urged to assist the call for an immediate ceasefire in Gaza after American opposition parties strongly criticized this action. They voiced their disapproval by expressing their” shocked” and” ashamed” at this sudden change in Indian foreign policy.

Beyond the rhetorical criticism, the Communist Party of India issued a joint statement in support of the UN’s call for an immediate ceasefire in Gaza. These actions taken by the opposition parties in India reveal how the political voices feel about India’s stance on the Israel-Hamas issue.

Pragmatically, India is not going to position itself as a reliable responsible customer in the international system if it does not pursue an equal foreign policy. If it wants to establish its status as a state with great humanitarian and democratic values, it takes on specific importance.

Nevertheless, New Delhi’s foreign forays into Hindutva are casting serious doubt on both the excellent and practical principles of its foreign policy. India doesn’t appear to be doing its talking.

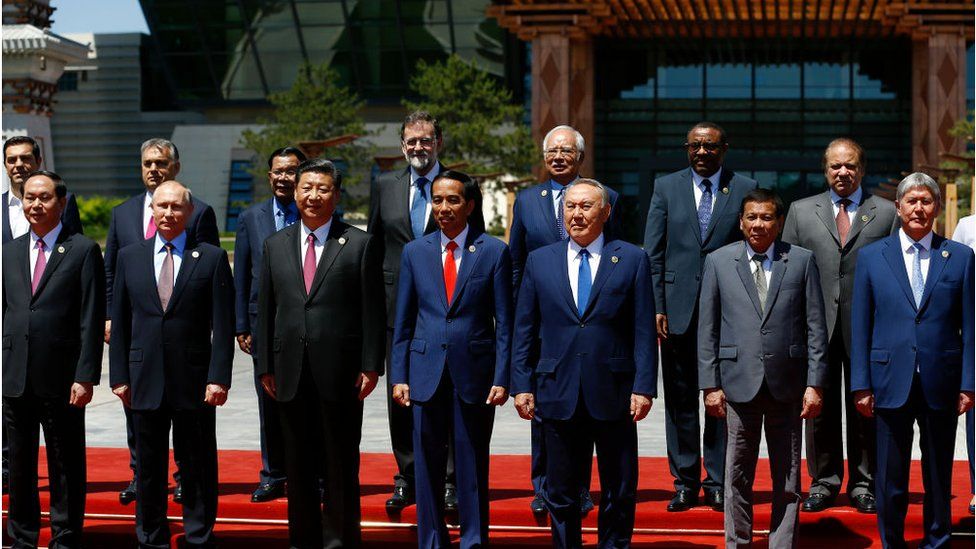

The American government decided to make” One Earth, One Family, and One Future” the style of its G20 president at the same conference where IMEC was established. Under Modi’s command, the BJP used the presidency to increase the political stakes in its favor rather than bringing this inclusive and global vision to fruition.

The Ukraine matter was put on hold at the same G20 Summit, which also widened tensions between India and Canada over the Sikh separatist movement and eventually led to an extraordinary diplomatic dispute between the two countries. India also used the G20 president to bring about peace in the disputed places.

In truth, India denies the Kashmiris living under its purview their basic right to self-determination, which is why it did not support the call for a cease-fire in Gaza under an anti-Muslim ruling party in charge of affairs.

The biggest obstacle to the effective implementation of IMEC is the anti-Muslim environment that the BJP, led by Narendara Modi, is fostering in India and projecting worldwide. The alarming rise in anti-Muslim fury and offences in India under the BJP has also been noted by the independent research organization Hindu Watch.

Hindutva-led forays may initially serve the BJP’s political agenda, but in the long run, they cannot guarantee the peace and stability that are essential for the success of financial initiatives, not to mention IMEC.