Sacred oxen predict bumper trade year

PUBLISHED: 10 May 2025 at 05: 46

NEWSPAPER SECTION: News

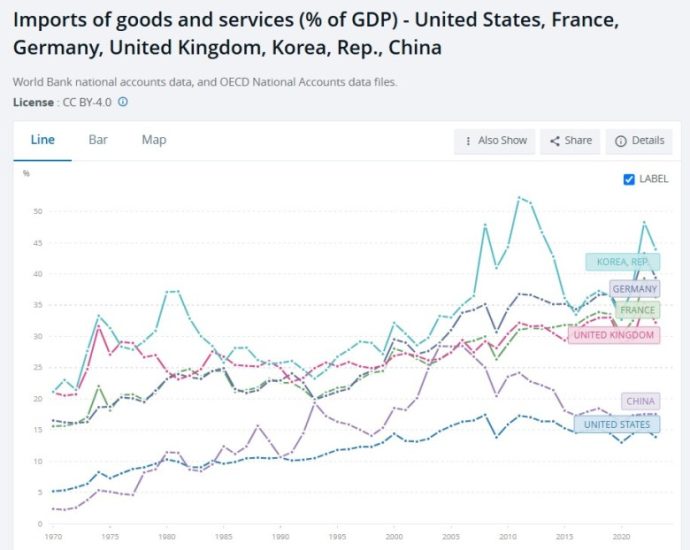

A note of enthusiasm came from the old Royal Ploughing Ceremony, where sacred cows foretold a successful season for international trade, as Thailand is under pressure from the threat of a 36 % mutual price by the United States on its imports.

The seven centuries-old ritual provided a proper moral increase while the state is eagerly awaiting a formal proposal from Washington to begin discussions aimed at mitigating the effects of the rough levy. The United States accounts for over 18 % of all shipments, which highlights the substantial financial stakes at play. It is one of the country’s major export markets.

The Royal Ploughing Ceremony, which took place on Friday at Sanam Luang’s Brahmin” Raek Na Khwan” rite, started with the Buddhist” Phuet Mongkhon” ceremony at the Temple of the Emerald Buddha and continued with the Brahmin” Phuet Mongkhon” rite at the temple on Friday, was presided over by their Majesties the King and Queen.

The spiritual oxen’s traditional form of divination, the sacred oxen, had the best food choices. They chose to drink alcohol this year, which indicates that the Thai economy is well off and that foreign trade and transportation are sturdy.

They also consumed grass and water, predicting sufficient snowfall and plentiful yields all year long.

The Sukhothai era in Thailand is where the Royal Ploughing Ceremony, a custom shared by many East Asian rice-growing countries, originated. The Phraya Raek Na, a senior official, now leads the ceremony, which was once performed by the King or members of the royal family. She interprets prophecies from precipitation and yields as federal agricultural projections.

Although discontinued following Thailand’s political shift in 1932, the ceremony was revived during King Rama IX’s rule to preserve tradition and highlight the importance of agriculture. It is currently broadcast nationwide every May and is held annually.

No one can say for certain whether the oxen’s prediction will be true, but it does provide a sense of hope for a country struggling with economic hardship.

The Royal Ploughing Ceremony, held on Friday at Sanam Luang ceremonial ground, is presided over by His Majesty the King and Her Majesty the Queen. Photo of a pool