Elihu Yale: The cruel and greedy slave trader who gave Yale its name

Getty Images

Getty Images

Yale University apologized informally next month for the connections its first leaders and donors had with slavery.

One brand that has since been closely watched in India has been Elihu Yale, the person who is the inspiration behind the Ivy League institution.

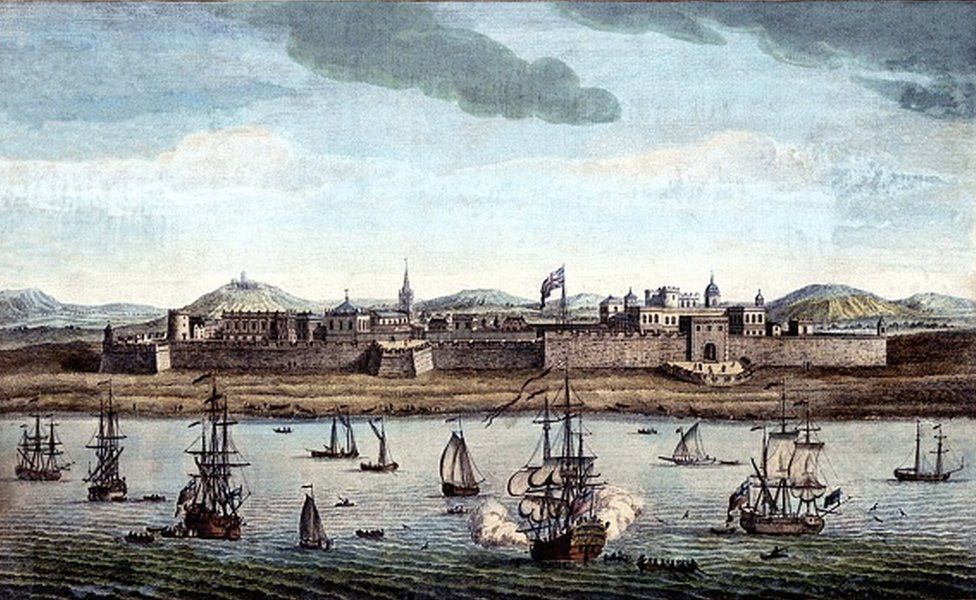

In Madras, in southern India ( present-day Chennai ), Yale held the title of” the university named after him,” which was a gift of about £1, 162 ($ 1, 486 ) that led to his appointment as the all-powerful governor-president of the British East India Company in the 17th century.

According to scholar Prof. Joseph Yannielli, who teaches present story at Aston University in Birmingham and has researched Yale’s connections to the Indian Ocean slave trade, “it’s the equivalent of £206, 000 now if you adjust it for prices.”

By today’s standards, it was not a sizable amount, but it did aid in the school in building an entirely new building.

Elihu Yale is now viewed as a colonial who plunderered India and worse traded in slaves, a person who is frequently described as a collector and collection of fine stuff and philanthropist who graciously donated to churches and charities.

The school’s explanation comes after more than three years of research into its troubled past. A team of researchers led by Yale writer David Blight examined the “university’s past with slavery, the role of slaves in the development of a Yale tower, or whose labor enriched popular leaders who made gifts to Yale,” according to a statement from the school.

The scope and size of the slave trade in the Indian Ocean, which ultimately matched that of the Atlantic, did not increase until the 19th century. However, the trade in folks along its shores as well as interior and to archipelago was pretty old on the Indian subcontinent, he writes, adding that Yale “oversaw several income, adjudications, and accountings of enslaved people for the East India Company.”

According to Prof. Yannielli, 12 million slaves were sold over the course of the Atlantic deal. He believes that the Indian Ocean deal was more extensive because it extended for much longer, connected South East Asia to the Middle East, and Africa.

The analysis of the past is crucial. Yale, which was established in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1701, is the third-oldest higher education institution in the United States, and its students include several US president and other notable figures.

The Collegiate School of Connecticut received hundreds of books on religion, books, treatments, story, and architecture, as well as a portrait of King George I, good textiles, and other priceless items beginning in 1713. The proceeds from selling them were used to build a fresh three-story developing with the name Yale College in his honor.

Rodney Horace Yale, a scholar and family member, claims that his donation “made the precarious living of Yale university a wonderful certainty” in his 19th-century biography of Elihu Yale.

Yale is also granted eternity because, despite there being no immediate ancestors of his, the Ivy League institution continues to bear his name.

In its explanation, the school stated that it would “work to strengthen variety, help equity, and market an environment of welcome, inclusion, and respect” and that it would work to “advance inclusive economic growth in New Haven,” a city that is primarily Black. However, it did not specify whether a name change was planned, and it has already turned down requests to do so in the history.

Elihu Yale, a three-year-old, and his family moved to England in April 1649 after being born there. In 1672, he took a administrative work with the East India Company and made his way to Fort St. George, the Light colony in Madras.

The company’s wages were “notoriously and absurdly low- from the president’s at £100 a month down to the apprentices ‘ at £5,” according to Rodney Horace Yale. According to him and another historians, its employees engaged in all kinds of trading for personal gain.

Yale spent more than 25 years in the ranks before being elected governor-president in 1687. He served that position until 1692 when he was fired for “using company funds for personal speculation, subjective government, and neglecting duty.”

The 51-year-old was a very powerful gentleman when he returned to England in 1699. In Queen’s Square on Great Ormond Street, he constructed” a majestic apartment” and stuffed it with valuable artifacts and fine art.

American newspapers named him as” a person known for his considerable charity” when he passed away in July 1721. However, researchers claim that he was also known for his violence and lust during his day in Madras.

His successors wrote in Rodney Horace Yale that he was accused of corruption and the strange deaths of many council members while he was governor, and that he had also been accused of ordering the dangling of one of his stable’s grooms” for riding a favorite horse of his without his permission.”

The writer adds that the case’s information does not “disagree with his figure,” but that there are some questions raised about it.

His most successful defense for a record of ignorance, brutality, sensuality, and greed while in authority at Madras may be his surroundings, he wrote.

Rodney Horace Yale, however, is accused of glossing over the role played by his ancestor in the prisoner trade by many other Elihu Yale scholars and new researchers.

There is no disputing that” Elihu Yale was a powerful and effective slave trader,” according to Prof. Yannielli, who combs through the Fort St. George colonial records.

Prof. Yannielli would n’t make a guess on how much money Yale made from slavery because it “ebbed and flowed” and because he traded in other things like diamonds and textiles, which “made it difficult to disentangle the profits he made from each trade.” However, he thinks that it was a sizable portion of his wealth.

” I may state that he had a lot of money.” He was in charge of regulating the prisoner business in the Indian Ocean. A devastating famine [in southern India ] in the 1680s caused a labor deficit, and Yale and other company officials profited from it, purchasing hundreds of slaves and transporting them to Saint Helena, he said.

Yale, he adds, “participated in a conference that required at least 10 prisoners to be sent on every ship sailing to Europe.” Fort St. George exported at least 665 prisoners in a single month in 1687. Yale enforced the 10 prisoners per vehicle rule as governor and senator of the Madras arrangement.

Prof. Yannielli, a former student at Yale, first began researching Elihu Yale’s connection to slave trade ten years ago when he saw a picture of the government waiting for a buttoned slaves.

Slavery was omnipresent in England at the time. It’s unclear whether he actually owned the prisoner or whether it was a member of his family [who owned it ] However, the baby serving him and some wine in the body demonstrates that servitude was a part of his daily life.

According to Prof. Yannielli, the reason some of Yale’s earlier writings have underplayed his connections to slavery may be due to a lack of historical data entry.

The more recent scholars who have chosen to ignore the evidence are “because they did n’t want to see it or may not have considered it important in the pre-Black Lives Matter era.”

Prof. Yannielli even refutes claims that Yale was an anarchist who, as governor, decreed the suspension of the slave trade between Madras and his successor.

Saying that he really ended slavery is a burning attempt at his persona. If you examine the initial documents, the Mughal king of India instructed the business to shut down. However, Yale was quickly up to it, and a year later, he had mandated the transportation of captives from Madagascar to Indonesia.

The 15th millennium saw the beginning of the opposition to slavery and colonization, and there were activists. But Yale was unquestionably not one.

Related Articles

The way to prevent yet another US bank crisis – Asia Times

This is the third part of a three-part series.

Financial system default crises can be rendered less frequent, and future bailouts of the financial system can be obviated, by private conversion of limited-liability corporate-form banks into non-corporate-form proportional-liability financial firms.

Such firms would be less prone to default than banks are, and would not need government insurance to protect their depositors – even if they keep the same employees, payrolls, physical plant and equipment, deposits, depositors, and outstanding loan portfolios as the banks from which they are converted.

Private conversion of banks to proportional-liability financial firms is impeded not only by its conceptual novelty – no one seems to have done it or publicly suggested it until now – but also by governmental obstacles that reduce its profitability or administrative feasibility.

Government insurance of bank deposits effectively eliminates the greatest profit incentive to convert a bank to a proportional-liability financial firm, namely that this conversion would lessen the default risk borne by its creditors including its uninsured depositors and hence the compensation that they demand.

In addition, central, state and local governments, having no experience of non-corporate proportional liability firms, make no provision for them in diverse kinds of business regulation and taxation. One example is the issuance of business charters, the standard term for which, “articles of incorporation,” reflects the ubiquity of the corporate form.

Partly due to the intrinsic advantages of converting banks into proportional-liability financial firms and partly due to political considerations described near the end of the second part of this three-part essay, the House Republican Caucus might best respond to any Biden administration request for a banking-system bailout during this session of Congress by conditioning its support for the requested bailout on prior enactment of legislation mandating imminent termination of governmental impediments to private conversions of banks into proportional-liability financial firms. Such legislation might aptly:

(1) mandate termination of FDIC bank deposit insurance within two years;

(2) repeal Title II of the Dodd-Frank Act, effective within two years;

(3) and prohibit (under the interstate commerce clause of the US Constitution) any federal, state or local government discrimination against proportional-liability financial firms relative to banks in any aspect of taxation or business regulation, including the issuance of business charters, effective within six months.

Higher Federal taxes, after two years, on banks not converted to proportional-liability financial firms, might also be warranted for banks that are not functionally specialized and structurally atypical but ought not to be necessary to induce private conversion of nearly all banks into proportional-liability financial firms.

The rest of this essay, except for a brief envoi, tells how and why proportional-liability financial firms would be better than banks both singly and collectively, i.e., why private conversions of banks into proportional-liability financial firms would be profitable, absent governmental impediments, and why governments should facilitate and encourage such conversions.

Problems of the corporate business form

The distinguishing feature of the corporate business form is limited liability – the exemption of the owners of a firm’s equity from any personal liability for the firm’s liabilities.

Limited liability causes the interests of a corporation’s equity owners to be increasingly at odds with the interests of its creditors as the value of a solvent corporation’s assets diminishes relative to the value of its liabilities.

As a solvent corporation (one with assets worth more than its liabilities) approaches insolvency (the point at which its assets are worth no more than its liabilities), its equity owners increasingly want it to take risks, even risks with negative expected values.

For the equity owners of a nearly insolvent corporation, whose equity is already worth next to nothing and cannot have a negative value due to limited liability, there is negligible scope for loss but great scope for gain by taking large risks, even if they are bad bets.

All the downside risk of a nearly insolvent corporation is born by its creditors, who increasingly prefer that a solvent corporation not take risks as it approaches insolvency. However, a corporation’s creditors,i.e., the owners of its liabilities, have no voting rights in the corporation’s control.

All voting rights in a corporation’s control typically are allocated to the owners of its equity, each share of equity being assigned one vote. Consequently, corporations, insofar as their management is informed by the interests of the holders of rights to vote in choosing their directors, tend to become more risk-loving and less profit-maximizing as they approach insolvency.

If a corporation’s equity trades in liquid markets, then individual owners of relatively small amounts of either its equity or its debt may be able to rely on exit (selling out) rather than voice (voting rights in corporate control) to protect their interests so management tends to be relatively independent of equity owners, save for those who own more equity than can be sold without lowering the market price of the corporation’s equity.

However, if there is no liquid market for a corporation’s equity or if the price at which a corporation’s equity trades is highly volatile, as it may be if the corporation is either highly leveraged financially or engages in business that is unusually risky, then exit substitutes less well for voice, and even owners of relatively small amounts of equity may be concerned to make the corporation’s management reflect the interests of its equity-owners.

If a corporation’s debt trades in liquid markets at prices that are not highly volatile, then individual owners of small amounts of its debt may be able to rely on exit (selling out) to protect their interests. Otherwise, a corporation’s financial creditors may try to protect their interests by “protective covenants” that constrain management but entail non-negligible monitoring and enforcement costs.

How the corporate form’s problems afflict banks

With no exceptions known to this writer, US banks are corporations. Their equity owners are totally exempt from personal liability for banks’ financial liabilities and typically are the only holders of voting rights in banks’ control.

Financial firms that are not corporations are not called banks. For example, credit unions resemble banks in their main activities – taking deposits and making loans – but differ from banks in not being corporations. A credit union is depositor-owned. It has no equity distinct from its deposits. Voting rights in its control are typically held solely by depositors in proportion to the value of their deposits.

The structural and behavioral characteristics of corporations described in this essay’s previous section also apply to banks, with variations described in the rest of this section.

A bank’s assets are chiefly the outstanding loans that it has made or loans made by other banks that it has bought, often in risk-diversifying bundles like mortgage-backed securities. The liabilities of a bank are chiefly its deposits, although many banks also issue debt securities.

The creditors of a bank are chiefly its depositors. The relatively few functionally specialized and structurally atypical banks for which not all of this is true fall outside the scope of this part of this essay.

If some of a bank’s deposits are government-insured, then their owners, unlike the bank’s other creditors, do not increasingly prefer that a solvent bank not take large risks as it approaches insolvency. Bank deposits are not readily tradable, but they can be withdrawn, often on demand or on short notice. Owners of uninsured bank deposits typically rely chiefly on exit by withdrawal to protect their interests.

Exit tends to substitute for voice less well for owners of a bank’s equity than for owners of the equity of non-financial corporations, even if there is a liquid market for the bank’s equity because the price of a bank’s equity tends to be more volatile than the price of the equity of a non-financial corporation.

Bank equity prices tend to be more volatile than the equity prices of non-financial corporations for two reasons. First, banks typically are more leveraged – i.e., they have more liabilities relative to equity – than non-financial corporations.

Their assets are created chiefly by lending money supplied by their depositors; their equity serves chiefly as a buffer against losses and tends to be little larger than is required by government regulators. Second, many factors affecting the value of banks’ assets, like market interest rates, are social constructs that can change rapidly.

For both these reasons, banking is an extraordinarily risky business. The impressively stable architecture long favored by banks, featuring multiple thick columns that appear able to withstand earthquakes, was deliberately crafted to belie this reality and inspire greater trust in banks than they in fact warrant.

Because exit tends to substitute for voice less well for owners of a bank’s equity than for owners of the equity of non-financial corporations, the management of a bank tends to be more responsive to the interests of its equity owners than is the management of a non-financial corporation.

Consequently, limited liability’s tendency to make corporations risk-loving and not profit-maximizing, insofar as corporate management is informed by the interests of its equity owners, to an extent that increases as a solvent corporation approaches insolvency, tends to afflict banks more strongly than non-financial corporations.

The tendency of limited liability to make solvent banks behave in increasingly default-prone ways as they approach insolvency, to an even greater extent than do non-financial corporations, is at best constrained, not eliminated, by greater government risk-control regulation of banks than of non-financial corporations.

In addition, the susceptibility of banks to default has greater negative externalities for the economy generally than does comparable susceptibility to default in non-financial corporations. Bank failures contract the money supply more than do failures of non-financial corporations, and therefore are uniquely likely to precipitate general economic contraction, as in 2007-08, or to aggravate an already severe economic contraction, as in 1932-33.

That is why the US government, through the FDIC, has since 1933 been the insurer of first resort for many bank deposits but has never been the insurer of first resort for any comparably large set of liabilities of non-financial corporations.

How to solve the problem: Convert banks to proportional-liability financial firms

A bank’s propensity to take unwarranted risks, which increases as a solvent bank approaches insolvency and thereby makes the bank prone to default, could be eliminated by restructuring the bank as a financial firm with a business form that is neither a joint stock company nor a corporation but is rather between the two.

In a joint stock company, anyone owning any of its equity is personally liable for all of its debt. Until well into the 19th century, this aspect of the then-dominant business form helped keep debtors’ prisons full. It also gave us “Ivanhoe”, which Sir Walter Scott wrote in two weeks in order to earn funds he needed to stay out of debtors’ prison after a joint stock company, some equity of which he owned, went bankrupt.

Beyond the problems entailed by impoverishing equity owners, joint stock companies suffered from the problem that the value of their debt depended in part on the value of the ever-changing personal wealth of each of an ever-changing set of equity owners, and hence was very hard to appraise.

In a corporation, by contrast, equity ownership entails no personal liability for any of the firm’s debt. Its default risk is born entirely by its creditors, who in the case of a bank are chiefly its depositors.

In Western countries, including the US and Britain, the corporate form was legalized and then quickly superseded the joint-stock company form during the 19th century. However, in that transition, an intermediate business form that rather obviously suggests itself was seldom if ever tried.

In that intermediate form, arguably best called the “proportional-liability” form, anyone who owns a specific proportion of its equity would be personally liable for the same proportion of its liabilities, or at least of its financial liabilities including debt securities that it has issued and, in the case of financial firms, deposits that it has accepted.

(For the purpose of rendering, equity owners less risk-loving, they need not be personally liable for the firm’s unforeseeable liabilities).

This proportional liability form would expose equity owners to slightly more personal liability than does the corporate form, but to far less personal liability than did the joint-stock company form. It could not impoverish any equity owner who did not foolishly overconcentrate his wealth in the equity of a single firm.

Moreover, a proportional-liability firm could include, in its charter or by-laws, limits on the amount of the firm’s equity that any individual could own, crafted to prevent overconcentration of personal wealth in its equity and in other assets with prices that co-vary strongly with the price of its equity.

Governmental regulators of financial firms might help in the enforcement of those rules, or promulgate and enforce such rules themselves. Securities brokerages have routinely enforced such rules on their clients for many decades.

Absent overconcentration of personal wealth in the firm’s equity and strongly price-covariant assets, the value of the firm’s debt would not vary significantly with changes either in its equity ownership or in the personal wealth of individual equity owners.

Such a proportional-liability firm’s default risk would be born wholly by its equity owners, although no equity owner would bear too much of it. Consequently, the owners of a proportional liability firm’s equity, unlike the owners of a corporation’s equity, would neither want the firm to take risks with negative expected values nor increasingly want it to do so as it approaches insolvency.

Although the proportionate-liability business form might have advantages over the corporate form for a broad range of firms, those advantages, both for the firm and for society generally, seem greatest for financial firms – the firms that we call “banks” when they are structured as corporations – because the high business risk and high leverage of banks tends to make exit substitute for voice less well for their voting-right-monopolizing equity owners than for the voting-right-monopolizing equity owners of non-financial corporations, which tends to make the management of banks more responsive to the flawed incentives of their equity owners than are the managements of non-financial corporations.

Allocating voting rights in proportional-liability financial firms to obviate deposit insurance

A proportional-liability firm could, by provisions of its charter or by-laws, divide voting rights in its control between the owners of its equity and the owners of its financial liabilities (its creditors or debtholders) in a ratio determined by the relative values of the firm’s assets and its liabilities.

So long as the market value of the firm’s assets exceeds the face value of its liabilities, equity owners would hold most of the voting rights in the firm’s control. If the market value of the firm’s assets fell below the face value of its liabilities, most of the voting rights in its control would become held by it is creditors – chiefly by its depositors in the case of a financial firm.

The assets of a proportionate-liability firm, like the assets of a corporation, would not be traded, hence would not have a directly observable market value. However, the value of the tradable equity of a proportional-liability firm would be the market value of its assets minus the present face value of its liabilities, per the basic accounting equation, E = A – L.

That equation is true for a proportional-liability firm and implies that A = E + L. E and L are directly observable, E being the price of traded equity and L being the sum of contractually specified future payments, each discounted at the risk-free interest rate for the term of its maturity.

Consequently, A, the market value of the firm’s assets, is readily ascertainable. This enables voting rights to be divided between the owners of the firm’s equity and the owners of its financial liabilities in proportion to the current relative values of A and L.

Among the advantages of allocating any proportional-liability firm’s voting rights in this way is that it obviates recourse to slow and costly bankruptcy courts as a means of transferring control of a firm from its equity owners to its creditors when the firm becomes insolvent – while also allowing the equity owners hope of regaining control of the firm if the owners of its financial liabilities choose not to liquidate it and it returns to solvency while under their control.

Among the advantages of allocating a proportional-liability financial firm’s voting rights in this way is that it obviates government insurance of depositors. As soon as the value of a proportional-liability financial firm’s assets (chiefly loans) becomes insufficient to cover the face value of its liabilities (chiefly deposits), majority control of the firm passes from its equity holders to its creditors (chiefly its depositors).

Consequently, either federal or state law or regulation might usefully require any proportional-liability financial firm to allocate its voting rights in this way, even though such voting right allocation has firm-specific efficiencies that could impel any proportional-liability firm to implement it spontaneously.

The problem with banks that has large negative external consequences and requires government insurance of bank deposits is that the incentives of the equity owners who exclusively own voting rights in a bank’s control conflict systematically with the incentives of depositors, and conflict with them more strongly as the bank’s risk of default (insolvency) grows.

That problem seems easily solved by replacing banks with proportional-liability financial firms. So kiss goodbye to the FDIC and to comparably unneeded deposit-insurance bureaucracies in other countries.

The benefits of proportional liability cannot be captured by a corporation

The market value of a corporation’s assets cannot readily be inferred from the price of its traded equity and the present face value of its liabilities, as the value of a proportional liability firm’s assets can. Consequently, a corporation cannot divide its voting rights between its equity owners and its creditors in proportion to the ratio of the market value of its assets to the present face value of its liabilities.

The same inability, readily to infer the market value of a corporation’s assets, precludes creating an efficient market for corporate default risk insurance that might obviate government insurance of bank deposits.

The basic accounting equation, E = A – L, is not true for a corporation. For a corporation, E = A – L + P, E being the market value of its equity, A being the putative value of its assets, L being the present face value of its liabilities, and P being the putative value of limited liability, which can in theory be priced as a put option (hence “P”) owned by equity owners that enables them to sell (A – L) to the firms’ creditors for nothing when A – L is worth less than nothing.

Because P, the value of that put, can never be less than A – L, E can never be worth less than zero. That is, due to limited liability, corporate equity – unlike the equity of a proportional-liability firm – can never have a negative market value.

Of the four variables in the corporate-form equation, E = A – L + P, only E and L are observable, E being tradable and L being contractually specified. Consequently, although the value of E + L can be observed and must equal the sum of A + P, neither the value of A nor the value of P can readily be ascertained.

There is no close-form solution to the problem of pricing either A or P by what is generally deemed the only rigorous and reliable method of pricing market-traded financial securities, namely the Black-Scholes-Merton option-pricing model developed in the 1970s or some variant of it.

The best way to try to estimate the value of either A or P that is consistent with Black-Scholes-Merton pricing apparently involves simultaneous iterative estimation of both A and P based on past and current prices of both. However, even this may fail to yield unique values for A and P.

Presumably for this reason, the prevailing method of pricing credit default swaps (CDS) does not apply the Black-Scholes-Merton option pricing model and is crude by comparison. Googling for “CDS mispricing” yields no smaller number of recent academic articles in the titles or bodies of which that term appears.

The impossibility of pricing corporate default risk rigorously may largely explain why there is still no liquid public market for credit default swaps, so that no reporting on the CDS markets is required or published by any regulatory entity.

It seems impossible to make a well-priced insurance market for corporate default risk, i.e., a market in which corporate equity owners could sell P and corporate creditors could buy P, which would enable them to synthesize the proportional-liability form and capture some of its advantages while the firm remains legally a corporation.

It seems impossible either to allocate corporate default risk efficiently or to allocate voting rights in corporate control optimally. The corporate business form apparently precludes both. To capture these benefits of the proportional-liability form, a corporation must be formally converted into a proportional-liability firm.

Envoi: the prospective loss of our heritage of bank-hatred

Proportional-liability financial firms would be no less able and willing than banks have been to foreclose on grandma’s farm, to evict widows and orphans from their homes, and to deny working people loans to pay for medical operations needed to save the lives of their children.

However, they, unlike banks, would neither often cause uninsured depositors to lose their life savings, nor, by defaulting en masse, recurrently precipitate economic contractions that deprive millions of their livelihoods. Proportional-liability financial firms might be merely loathed and despised rather than viscerally hated, as banks have been by most people ever since usury became tolerated and institutionalized.

Saddeningly, we will suffer a vast and irretrievable cultural loss if our financial institutions cease to inspire hatred in enduring them, wit in mocking them and bravery in fighting them.

Without banks, how will our grandchildren be able to appreciate Dickens’ “Little Dorrit” or Wolfe’s “Bonfire of the Vanities?” How will they be able to savor Barry’s doubling in Peter Pan of Captain Hook, a child-murdering pirate, and George Darling, a childhood-killing banker?

How will they grasp the symbol-inversion in Mary Poppins’ use of a black umbrella, a badge of office borne by Victorian London bankers even under clear skies, to fly children away from the clutches of their joyless banker-father?

Without banks, how will our posterity be able to empathize with the Americans of the Great Depression, whose most-admired heroes, during and after the nationwide bank failures of 1932-33, were bank robbers like John Dillinger, Pretty Boy Floyd, Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow?

Without banks, how will future generations feel why the Paris Commune and the Bolshevik Revolution were so appealing to so many? How will they feel what has been conveyed by Jew-hatred’s portrayal of Jews as bankers or would-be bankers, which, after the German bank failures of 1931, contributed mightily to the rise of Hitler and the Holocaust?

If banks and their chronic default crises end, even without ending loan denials, foreclosures and evictions, then much of our past will be gone with the wind, as much of America’s past was when slavery ended, even though few freed slaves got their promised forty acres and a mule.

IWD Deal Analysis: How IIX’s WLB6 Orange bond helps women’s livelihoods in Asia | FinanceAsia

In a growing regional trend, December 2023 saw the sixth issuance of Impact Investment Exchange (IIX)’s Women’s Livelihood Bond (WLB) Series, the $100 million Women’s Livelihood Bond 6 (WLB6).

Altogether the IIX, since 2017, has raised $228 million to support women’s economic empowerment in Asia, with the overall trend in deal size on an upward trend. FinanceAsia discussed the investors, the rationale and the processes involved in order to celebrate International Women’s Day (IWD) 2024 on Friday, March 9 and the drive towards diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) across the region.

The closing of WLB6 marked the world’s largest sustainable debt security and was issued in compliance with the Orange Bond Principles and aims to uplift over 880,000 women and girls in the Global South.

Global law firm Clifford Chance advised Australia and New Zealand Banking Group (ANZ) and Standard Chartered Bank pro bono as placement agents.

Proceeds from WLB6 will be used to promote the growth of women-focused businesses and sustainable livelihoods across six sectors: agriculture; water and sanitation; clean energy; affordable housing; SME lending and microfinance across India, Cambodia, Indonesia, Kenya and Vietnam. 100% of the $100 million proceeds designed to advance UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 5: gender equality and 25-30% designed to advance SDG 13 — climate action.

Robert Kraybill, chief investment officer, IIX, told FA: “The Women’s Livelihood Bond (WLB) Series is a blended finance instrument that pools capital from public-sector development finance institutions and private-sector investors. The public sector investors provide risk-tolerant “first-loss” capital in the form of subordinated notes, while the private sector investors purchase the senior bonds.”

“The WLB Series targets a range of private sector investors seeking a combination of high impact with low risk and an appropriate return. From the outset, beginning with the WLB1, the bonds have attracted both family offices and institutional investors. Initially, this was skewed towards family offices. As the WLB issuances increased, we saw increased interest from institutional investors, such that over 90% of the WLB6 was placed with institutions,” added Kraybill.

For WLB6, there were global investors on the deal including from the US, Europe and Asia Pacific (Apac). The WLB6 bonds comply with the EU and UK securitisation regulations, making it easier for European institutional investors to participate. For example, one of the investors was Dutch pension fund APG Asset Management which invested $30 million.

Kraybill said: “Throughout building the loan portfolios for the WLBs – from sourcing and screening to due diligence – we integrate traditional credit criteria with impact criteria. We look to invest in companies meeting our credit and financial criteria while delivering meaningful positive impact.”

“We are proud that we have not experienced any payment defaults or credit losses on any of the WLB loan portfolios, demonstrating the resilience of the high-impact women-focused businesses that we work with, even in the face of challenges posed by the Covid-19 pandemic. The first two bonds in the WLB Series – WLB1 and WLB2 – have matured and been fully retired, meeting all of their obligations to bondholders,” Kraybill added.

The IIX, which is headquartered in Singapore and has offices in Australia, Bangladesh, Brunei, India, Indonesia, the Philippines, Sri Lanka and Vietnam, also tracks the impact outcomes generated by its investment throughout the life of the bonds and reports on the targets. WLB1 and WLB2 exceeded impact projections, according to IIX.

Complex deal

Given the number of parties involved and a myriad of regulations and compliance, the deal was not easy to put together.

Gareth Deiner, partner at Clifford Chance, explained to FA the law firm’s role in the deal: “We’ve been involved for several years on these transactions, and this is not the first woman’s livelihood bond that the IIX team has put together.”

Singapore-based Deiner continued: “Historically, we have acted on the trustee side, but we have been advising the lead managers of the transaction for the last three offerings. It’s approximately a three to four month execution process to make sure we get the documentation agreed and the structure in place. IIX do the underlying due diligence on the borrowers, which is necessary given that the financing is raised from the international capital markets. Together with their counsel, they work on the disclosure in the offering document for the bond transaction.”

“As counsel to the lead managers, we are responsible for the underlying contractual documentation for the notes and the offering, but it’s IIX who retain control over the loan documentation with the notes proceeds end-users, and putting the loan pool together. They’re doing due diligence on the on the underlying borrowers of the deal,” he explained.

This is backed up by IIX’s due diligence. IIX’s Kraybill explained: “The financial due diligence conducted by our credit team is similar to that of other emerging market lenders. What sets us apart is the upfront impact due diligence and ongoing impact monitoring and reporting conducted by our impact assessment team. Our team screens potential investments against rigorous eligibility criteria to ensure they contribute to positive outcomes for underserved women and gender minorities in the Global South while often empowering women as agents of climate action.”

Navigating US legal rules and dealing with investors from around the world also added to the complexity.

Deiner said: “Dealing with a wide range of investors, including qualified institutional buyers in the US, we needed to comply with US federal securities law, including limiting the sale of the notes to qualified purchasers under the US Investment Company Act. There were also certain structural considerations raised by the EU and UK securitisation regulation.”

“From a legal perspective, it was an interesting deal because there’s a wide range of highly technical substantive law, which required the input from specialists across the Clifford Chance network. We have the expertise across the globe and do a lot of sustainable financing work,” continued Deiner.

“Recently we’ve advised on some market-leading and groundbreaking transactions in terms of bringing sustainability finance technology to capital markets transactions,” he added.

However, this deal, in particular, involved social governance goals.

Deiner explained: “What we like about this particular transaction is that so much of the Environmental Social and Governance (ESG) agenda is about the environmental (E) angle, such as green bonds related to carbon transition and climate action. That encompasses sustainable development goal 13 of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG).”

“However, you rarely hear about sustainable finance transactions that focus on the S and the G in ESG, which IIX champions. Each of the sustainable development goals (SDG) has its own hue, its own colour. This transaction focusses on SDG 5, which is gender equality, and are referred to as Orange bonds – orange being the hue for SGD 5. In addition, IIX has developed its own framework and principles to really drive that S in the ESG,” he added.

Tracking societal impact

There is still a key issue on how to track the impact of where the money ends up.

IIX’s due diligence process includes interviews with beneficiaries and stakeholders of investees, using its own digital impact assessment tool to incorporate input from a broad group of female beneficiaries. This verifies impact claims while giving a voice and value to the women it is assisting, according to Kraybill.

He continued: “Our selection process for projects funded through WLB6 closely aligns with the objectives of The Orange Movement. Each of the bonds in the WLB Series adheres to The Orange Bond Principles, which focuses on empowering women, girls, and gender minorities, particularly in climate action and adaptation.”

IIX looks at the potential of each project’s mission, vision, goals, and business structure, to evaluate alignment with the core values of the WLB Series and The Orange Movement. Its impact assessment team conducts due diligence to ensure selected projects meet criteria outlined by The Orange Movement and contribute to promoting gender equity and addressing climate challenges in emerging markets, according to Kraybill.

With the rise of bonds connected to ESG and DEI, the scrutiny from investors is also increasing, especially with the prevalence of greenwashing.

Clifford Chance’s Deiner said: “The legal landscape for green bonds and sustainability-linked bonds has evolved considerably in recent years, particularly regarding due diligence. When a company issues a green bond under a green bond framework, substantial work is required to ensure the bond’s integrity. This diligence has become a critical factor in investment decisions, as investors need to be confident that the environmental credentials are genuine and not merely an instance of greenwashing.”

“One of the key parts of the Orange bond initiative is achieving transparency in the investment process and decision, and the subsequent reporting, as the proceeds are going to an issuer who is on-lending it again, to, for example, a microfinance lender. It’s a combination of seeking an investment return and a view on the credit profile. The funds have specific objectives regarding capital allocation, and the appeal of the Orange bond aspect aligns with this focus,” Deiner added.

$10 billion goal

The IIX has an ambitious goal of mobilising $10 billion by 2030 and optimism abounds.

Kraybill said: “We remain optimistic about reaching our ambitious goal through sustained collaboration and concerted action, empowering women and girls worldwide while fostering inclusive and sustainable development.”

“Partnerships with the Orange Bond Steering Committee organisations, like the Australian government’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), the UN Capital Development Fund (UNCDF), Nuveen, and others, are vital in this endeavour. Together, we aim to build a gender-empowered financing system, mobilise new capital, and accelerate progress toward gender equality and women’s empowerment globally,” Kraybill added.

The Orange Movement is also building “Orange Alliances” at regional and national levels to bring together gender lens investors and other stakeholders. IIX is conducting training programs to train and certify Orange Bond verification agents.

“We’re introducing an “Orange Seal” for MSMEs and other organisations, which enhances their gender, DEI, and climate bona fides. We have expanded our transaction tagging functionality to include innovative finance instruments that adhere to the Orange Bond Principles framework. Furthermore, we’re eagerly anticipating the launch of the Orange Loan Facility, alongside numerous other initiatives to further the Orange Movement’s mission,” Kraybill said.

He said: “We remain optimistic about reaching our ambitious goal through sustained collaboration and concerted action, empowering women and girls worldwide while fostering inclusive and sustainable development.”

The next bond could potentially be much larger than WLB6’s $100 million.

Clifford Chance’s Deiner is also optimistic: “There’s a flow of transactions that we’re going to see over the next 12 months, and this an area that people are paying more attention to. The transactions have grown considerably over the years. These transactions have involved deals from around $20 million up to the latest offering of $100 million. So, there is clearly increasing demand for these transactions each year.”

Standard Chartered declined to provide a comment for the article.

¬ Haymarket Media Limited. All rights reserved.

IWD Deal Analysis: IIX’s WLB6 Orange Bond helping women’s livelihoods in Asia | FinanceAsia

In a growing regional trend, December 2023 saw the sixth issuance of Impact Investment Exchange (IIX)’s Women’s Livelihood Bond (WLB) Series, the $100 million Women’s Livelihood Bond 6 (WLB6).

Altogether the IIX, since 2017, has raised $228 million to support women’s economic empowerment in Asia, with the overall trend in deal size on an upward trend. FinanceAsia discussed the investors, the rationale and the processes involved in order to celebrate International Women’s Day (IWD) 2024 on Friday, March 9 and the drive towards diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) across the region.

The closing of WLB6 marked the world’s largest sustainable debt security and was issued in compliance with the Orange Bond Principle and aims to uplift over 880,000 women and girls in the Global South.

Global law firm Clifford Chance advised Australia and New Zealand Banking Group (ANZ) and Standard Chartered Bank pro bono as placement agents.

Proceeds from WLB6 will be used to promote the growth of women-focused businesses and sustainable livelihoods across six sectors: agriculture; water and sanitation; clean energy; affordable housing; SME lending and microfinance across India, Cambodia, Indonesia, Kenya and Vietnam. 100% of the $100 million proceeds designed to advance UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 5: gender equality and 25-30% designed to advance SDG 13 — climate action.

Robert Kraybill, chief investment officer, IIX, told FA: “The Women’s Livelihood Bond (WLB) Series is a blended finance instrument that pools capital from public-sector development finance institutions and private-sector investors. The public sector investors provide risk-tolerant “first-loss” capital in the form of subordinated notes, while the private sector investors purchase the senior bonds.”

“The WLB Series targets a range of private sector investors seeking a combination of high impact with low risk and an appropriate return. From the outset, beginning with the WLB1, the bonds have attracted both family offices and institutional investors. Initially, this was skewed towards family offices. As the WLB issuances increased, we saw increased interest from institutional investors, such that over 90% of the WLB6 was placed with institutions,” added Kraybill.

For WLB6, there were global investors on the deal including from the US, Europe and Asia Pacific (Apac). The WLB6 bonds comply with the EU and UK securitisation regulations, making it easier for European institutional investors to participate. For example, one of the investors was Dutch pension fund APG Asset Management which invested $30 million.

Kraybill said: “Throughout building the loan portfolios for the WLBs – from sourcing and screening to due diligence – we integrate traditional credit criteria with impact criteria. We look to invest in companies meeting our credit and financial criteria while delivering meaningful positive impact.”

“We are proud that we have not experienced any payment defaults or credit losses on any of the WLB loan portfolios, demonstrating the resilience of the high-impact women-focused businesses that we work with, even in the face of challenges posed by the Covid-19 pandemic. The first two bonds in the WLB Series – WLB1 and WLB2 – have matured and been fully retired, meeting all of their obligations to bondholders,” Kraybill added.

The IIX, which is headquartered in Singapore and has offices in Australia, Bangladesh, Brunei, India, Indonesia, the Philippines, Sri Lanka and Vietnam, also tracks the impact outcomes generated by its investment throughout the life of the bonds and reports on the targets. WLB1 and WLB2 exceeded impact projections, according to IIX.

Complex deal

Given the number of parties involved and a myriad of regulations and compliance, the deal was not easy to put together.

Gareth Deiner, partner at Clifford Chance, explained to FA the law firm’s role in the deal: “We’ve been involved for several years on these transactions, and this is not the first woman’s livelihood bond that the IIX team has put together.”

Singapore-based Deiner continued: “Historically, we have acted on the trustee side, but we have been advising the lead managers of the transaction for the last three offerings. It’s approximately a three to four month execution process to make sure we get the documentation agreed and the structure in place. IIX do the underlying due diligence on the borrowers, which is necessary given that the financing is raised from the international capital markets. Together with their counsel, they work on the disclosure in the offering document for the bond transaction.”

“As counsel to the lead managers, we are responsible for the underlying contractual documentation for the notes and the offering, but it’s IIX who retain control over the loan documentation with the notes proceeds end-users, and putting the loan pool together. They’re doing due diligence on the on the underlying borrowers of the deal,” he explained.

This is backed up by IIX’s due diligence. IIX’s Kraybill explained: “The financial due diligence conducted by our credit team is similar to that of other emerging market lenders. What sets us apart is the upfront impact due diligence and ongoing impact monitoring and reporting conducted by our impact assessment team. Our team screens potential investments against rigorous eligibility criteria to ensure they contribute to positive outcomes for underserved women and gender minorities in the Global South while often empowering women as agents of climate action.”

Navigating US legal rules and dealing with investors from around the world also added to the complexity.

Deiner said: “Dealing with a wide range of investors, including qualified institutional buyers in the US, we needed to comply with US federal securities law, including limiting the sale of the notes to qualified purchasers under the US Investment Company Act. There were also certain structural considerations raised by the EU and UK securitisation regulation.”

“From a legal perspective, it was an interesting deal because there’s a wide range of highly technical substantive law, which required the input from specialists across the Clifford Chance network. We have the expertise across the globe and do a lot of sustainable financing work,” continued Deiner.

“Recently we’ve advised on some market-leading and groundbreaking transactions in terms of bringing sustainability finance technology to capital markets transactions,” he added.

However, this deal, in particular involved social governance goals.

Deiner explained: “What we like about this particular transaction is that so much of the Environmental Social and Governance (ESG) agenda is about the environmental (E) angle, such as green bonds related to carbon transition and climate action. That encompasses sustainable development goal 13 of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG).”

“However, you rarely hear about sustainable finance transactions that focus on the S and the G in ESG, which IIX champions. Each of the sustainable development goals (SDG) has its own hue, its own colour. This transaction focusses on SDG 5, which is gender equality, and are referred to as Orange bonds – orange being the hue for SGD 5. In addition, IIX has developed its own framework and principles to really drive that S in the ESG,” he added.

Tracking societal impact

There is still a key issue on how to track the impact of where the money ends up.

IIX’s due diligence process includes interviews with beneficiaries and stakeholders of investees, using its own digital impact assessment tool to incorporate input from a broad group of female beneficiaries. This verifies impact claims while giving a voice and value to the women it is assisting, according to Kraybill.

He continued: “Our selection process for projects funded through WLB6 closely aligns with the objectives of The Orange Movement. Each of the bonds in the WLB Series adheres to The Orange Bond Principles, which focuses on empowering women, girls, and gender minorities, particularly in climate action and adaptation.”

IIX looks at the potential of each project’s mission, vision, goals, and business structure, to evaluate alignment with the core values of the WLB Series and The Orange Movement. Its impact assessment team conducts due diligence to ensure selected projects meet criteria outlined by The Orange Movement and contribute to promoting gender equity and addressing climate challenges in emerging markets, according to Kraybill.

With the rise of bonds connected to ESG and DEI, the scrutiny from investors is also increasing, especially with the prevalence of greenwashing.

Clifford Chance’s Deiner said: “The legal landscape for green bonds and sustainability-linked bonds has evolved considerably in recent years, particularly regarding due diligence. When a company issues a green bond under a green bond framework, substantial work is required to ensure the bond’s integrity. This diligence has become a critical factor in investment decisions, as investors need to be confident that the environmental credentials are genuine and not merely an instance of greenwashing.”

“One of the key parts of the Orange bond initiative is achieving transparency in the investment process and decision, and the subsequent reporting, as the proceeds are going to an issuer who is on-lending it again, to, for example, a microfinance lender. It’s a combination of seeking an investment return and a view on the credit profile. The funds have specific objectives regarding capital allocation, and the appeal of the Orange bond aspect aligns with this focus,” Deiner added.

$10 billion goal

The IIX has an ambitious goal of mobilising $10 billion by 2030 and optimism abounds.

Kraybill said: “We remain optimistic about reaching our ambitious goal through sustained collaboration and concerted action, empowering women and girls worldwide while fostering inclusive and sustainable development.”

“Partnerships with the Orange Bond Steering Committee organisations, like the Australian government’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), the UN Capital Development Fund (UNCDF), Nuveen, and others, are vital in this endeavour. Together, we aim to build a gender-empowered financing system, mobilise new capital, and accelerate progress toward gender equality and women’s empowerment globally,” Kraybill added.

The Orange Movement is also building “Orange Alliances” at regional and national levels to bring together gender lens investors and other stakeholders. IIX is conducting training programs to train and certify Orange Bond verification agents.

“We’re introducing an “Orange Seal” for MSMEs and other organisations, which enhances their gender, DEI, and climate bona fides. We have expanded our transaction tagging functionality to include innovative finance instruments that adhere to the Orange Bond Principles framework. Furthermore, we’re eagerly anticipating the launch of the Orange Loan Facility, alongside numerous other initiatives to further the Orange Movement’s mission,” Kraybill said.

He said: “We remain optimistic about reaching our ambitious goal through sustained collaboration and concerted action, empowering women and girls worldwide while fostering inclusive and sustainable development.”

The next bond could potentially be much larger than WLB6’s $100 million.

Clifford Chance’s Deiner is also optimistic: “There’s a flow of transactions that we’re going to see over the next 12 months, and this an area that people are paying more attention to. The transactions have grown considerably over the years. These transactions have involved deals from around $20 million up to the latest offering of $100 million. So, there is clearly increasing demand for these transactions each year.”

Standard Chartered declined to provide a comment for the article.

¬ Haymarket Media Limited. All rights reserved.

Commentary: There’s a US$3 billion opportunity if Singapore closes women’s health gap

WOMEN’S Wellness If MATTER TO MEN TOO

To address the health disparities faced by people, a multidimensional approach encompassing tailored study, equal access to meet for objective solutions, and increased funding is needed.

Now, research and data collection fall little in addressing children’s special health needs. Just half of global research describe results by female, with outcomes less advantageous for women virtually two- thirds of the time compared to men. Without clearer knowledge on how health problems and treatment may affect people separately, these differences impact the quality of attention they receive.

Disparities is even endure in treating conditions like heart disease and problems administration, where women usually receive poor treatment, leading to poorer health outcomes. For example, men are three times more likely than women to get cardiovascular resynchronisation treatments for tachycardia. These distinctions contribute to over one- second of the global health space affecting people.

Lastly, despite achievements in integrating people into research and clinical studies, opportunities in women’s health also remain overwhelmingly low. For example, between 2009 and 2020, just 5.9 per share of grants in Canada and the United Kingdom focused on women- specific outcomes or women’s wellness issues.

We need to appear at women’s wellness as more than better care for women- but as a base for total political happiness and progress. Bridging the health space had set off a network effect that positively impacts individuals, communities, and economy in Singapore and the universe.  ,

Lucy Perez is Top Partner with McKinsey &, Company and health capital co- head of the McKinsey Health Institute. Sachin Chaudhary is Top Partner with McKinsey &, Company and president of the medical practice in Southeast Asia.

The Sleepwalkers of 1914 are the Bedwetters of 2024 – Asia Times

Subscribe right away for access at a special price of only$ 99/year.

Villain present or casus belli in a European military leak?

In a recent leaked conference between European military officials discussing possible military activities in Ukraine, Uwe Parpart unpacks the revelations made. The conversation, which was made public and was intercepted by Russian intelligence, demonstrates a significant lack of proper planning and operational security. The entirety of Parpart’s criticism may be read here.

China adheres to the elements

Following the National People’s Congress’s lack of significant initiatives to promote consumption or help the home market, David P. Goldman discusses the sorrow among Chinese equity investors. Long-term stability and democratic cohesion are priorities for Beijing over short-term growth concerns.

Geopolitical danger hedge: Get USD/PLN volatility, offer USD/CZN volatility.

A political risk wall strategy involving currency volatility is suggested by David P. Goldman. PLN volatility is relatively small compared to CZK volatility, which gives investors a chance to capitalize on possible fluctuations as a cost-effective hedge against escalating local tensions.

The European right is on the cusp of a victory.

Diego Faßnacht discusses French President Emmanuel Macron’s request to send NATO troops to Ukraine and opposition head Marine Le Pen’s existing social position, whose party is projected to win significant seats in the forthcoming European Parliament elections, which represents a centrist turn in Western politics.

Rising increase risks for Ukraine as Russia gains floor.

James Davis provides a thorough analysis of the Ukrainian military condition, including information on possible maneuvers by Russian troops in the future, the influence of new US sanctions on Russia’s financial plans and international business relations, as well as the potential risks of further escalation in Ukraine and challenges to American support for Kiev.

China is being driven over, away, and forward by US sanctions.

Scott Foster evaluates President Biden’s speech regarding the US auto company’s competitiveness, the perceived danger from Chinese supremacy, and policy introduced by Republican Senator Josh Hawley to drastically raise tariffs on imported Chinese cars in an effort to protect the US automobile market.

Volume One 2024 magazine out now | FinanceAsia

We are delighted to announce that the first volume of FinanceAsia’s 2024 bi-annual magazine, is now available for your perusal.

In this edition, we celebrate all the winners the FinanceAsia Achievement Awards 2023 and explain the rationale behind why each institution won. In addition to the Deal and House Awards for Asia and Australia and New Zealand (ANZ); this year we added a new category, the Dealmaker Poll, which recognises key individuals and companies based on market feedback.

In feature format, Christopher Chu examines the potential and reach of artificial intelligence (AI) in Asia – the fast-moving technology is presenting both huge challenges and opportunities for investors. While it remains caught in the cross-hairs of geopolitics and regulation, he examines how AI could be a game-changer for productivity.

Ryan Li explores the proposed breakup of Chinese giant Alibaba and how the firm’s ambitions fit in with wider developments across China’s tech sector.

Also in the magazine, Andrew Tjaardstra reviews IPO activity across key Asian markets in 2023 and looks ahead to how public markets might perform in 2024 – while it certainly hasn’t been an easy ride for the region’s equity markets over the last 12 months, there have been some bright spots, notably India and Japan, which are set to continue their momentum this year.

Finally, read Ella Arwyn Jones’ exclusive interview with Rachel Huf, the new Hong Kong CEO of Barclays. Huf shares her transition from lawyer to leader, offering insights around her career path and the strategic direction of the bank in the Special Administrative Region (SAR) over months to come.

¬ Haymarket Media Limited. All rights reserved.

DBS CEO Gupta’s total pay dropped 27% to US$8.3 million in 2023

According to the lender’s annual report, Piyush Gupta, CEO of Singapore’s largest bank DBS Group and one of the highest-paid CEOs in the country, his total compensation for 2023 decreased by 27.3 percent, according to the company’s annual report, which was released on Wednesday ( Mar 6 ). According toContinue Reading

Next US financial crisis could look like the last – Asia Times

This is the second part of a three-part series

During the last financial crisis, Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, both now teaching at the Charles River campus of Plagiarism University, wrote an engagingly readable and well-received book, This Time is Different (2009), describing ways in which debt boom and default cycles have varied little since the Middle Ages.

The most amusing of these similarities is that those who profit most from each such cycle’s bubble phase sustain it by assuring the gullible that this debt bubble, unlike all its predecessors, will not end badly – that this time is different.

Reinhart’s and Rogoff’s warning seems best appreciated as reverse-reprising Tolstoy’s bon mot, in “Anna Karenina”, that although “all happy families are alike, every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

Although all debt bubbles end unhappily, the happy thoughts used to assure each bubble’s victims that it will not end unhappily must differ enough from the happy thoughts used to sustain recent previous bubbles to seem credible, at least to the gullible.

If a US financial crisis occurs in 2024, it will be novel in certain ways. Of these, the most widely anticipated is that it will occur electronically. Fear that fast transactions via the Internet and “disinformation” via insufficiently censored electronic media might cause bank runs to spread rapidly have recently troubled elites both in the US and Europe.

Less widely discussed is the possibility that the alienation of customers by the growing electronic automation of financial institutions could aggravate a financial crisis.

During the past decade, bankers and brokers have increasingly hidden from depositors behind websites that often function poorly and phone answering services that often have long wait times and ill-trained staff. This has coincided with the closing of so many branch offices as to give rise to a new financial term, “banking desert,” to describe any of the increasingly numerous and large areas with no physical banking services in which millions of disproportionately lower-income Americans now live.

As an executive of a US-based digital services firm recently observed in discussing the limits of bank automation, having human contact with staff gives a bank’s depositors more confidence in the bank. What might move a depositor to trust bankers who hide from him behind new infotech, and whom he never meets in person? And how can a banking desert dweller tell a failing bank from a bank whose website is dysfunctional or whose phone service wait time is impossibly long?

It seems not to have occurred to America’s ruling elites that the automation of banking might aggravate a banking crisis in these ways. Perhaps that’s because folks who live in America’s wealthier towns and neighborhoods not only still have branch banks, but increasingly have branch banks newly redesigned to include coffee bars and social lounges. Only from working-class stiffs do bankers hide behind websites and phone banks.

A more important novel aspect of any 2024 financial crisis is that it will occur after the widely touted but still little-tested replacement of taxpayer-funded bank bailouts by financial industry-funded bank “bail-ins” authorized by Title II of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, enacted on July 21, 2010, and implemented by Title 12, Part 380, of the Code of Federal Regulations, promulgated on January 25, 2011.

Title II of the Dodd-Frank Act, titled “Orderly Liquidation Authority,” authorizes the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) to conduct “ball-in” liquidations, funded by the financial sector, of failed or failing banks or bank-like financial firms, in the hope of obviating taxpayer-funded bailouts.

Title II authorizes the Secretary of the Treasury to put into FDIC receivership, pending liquidation, any bank or bank-like financial firm that is in default or deemed by the Secretary to be in danger of default, and the default of which may endanger general economic stability.

Title II authorizes the FDIC to use the equity, debt securities or uninsured deposits of the financial firm in receivership, salaries or bonuses recently paid to that firm’s management or directors, or assessments levied on other financial firms, in order to honor that firm’s obligations to its employees and the government, including to the FDIC as insurer of its small depositors.

The financial assets of the FDIC, which insures deposits of less than $250,000 at US banks, are grossly inadequate to respond to any large financial crisis either by bailouts or by bail-ins. As of June 30, 2023 (the most recent date for which relevant data seem to have been published), the FDIC’s Deposit Insurance Fund (DIF) had a balance of $119 billion.

The aggregate face value of deposits at US banks was then and is now above $17 trillion. Authoritative data on the total face value of FDIC-insured deposits seem not to be publicly available but diverse observers have recently estimated that slightly more than half of US bank deposits are FDIC-insured. If so, then the FDIC’s contingent liabilities appear to exceed its assets available to cover those liabilities by a factor of at least 70.

Consequently, for the Secretary of the Treasury and the FDIC to respond to any systematic banking crisis in which many US banks default or are at risk of default – or in which even one of the largest US banks defaults or is at risk of default – entails expropriation of private financial assets.

Section 214 of the Dodd-Frank Act reads in full:

- Liquidation required: All financial companies put into receivership under this subchapter shall be liquidated. No taxpayer funds shall be used to prevent the liquidation of any financial company under this subchapter.

- Recovery of funds: All funds expended in the liquidation of a financial company under this subchapter shall be recovered from the disposition of assets of such financial company, or shall be the responsibility of the financial sector, through assessments.

- No losses to taxpayers: Taxpayers shall bear no losses from the exercise of any authority under this subchapter.

However, section 206 of the Dodd-Frank Act requires that any action under Title II serve not merely interests specific to the company in receivership, but the stability of the economy as a whole.

The task of deciding whose assets should be expropriated and whose should not be expropriated in the interest of general economic stability is not an enviable one. No matter how carefully such decisions are made, they may evoke public complaints and considerable resistance from within the far-from-powerless financial industry.

Any financial firm that owns either equity or debt securities issued by another financial firm in FDIC receivership or uninsured deposits in such a financial firm might cite Section 206 of the Dodd-Frank Act to argue that it should be exempted in whole or part from FDIC expropriation of those assets on the ground that their expropriation would increase its own risk of default, thereby imperiling the stability of the whole economy.

Financial firms might even argue collectively – and plausibly – that the whole financial sector should be subjected to only minimal assessments to fund liquidations under Title II, on the grounds that to extract large assessments from banks in a time of systemically elevated risk of bank default tends further to elevate systematic bank default risk.

This is particularly true insofar as such assessments increase – as provisions of Title II suggest that they should increase either over time or across firms – with the appraised risk of default by any financial firm from which such assessments are collected.

Any such limitation of assessments could leave the FDIC short of resources to cope with a serious financial crisis, impelling the Executive Branch to ask Congress once again to appropriate funds to bail out rather than to liquidate diverse financial institutions in danger of default.

Inasmuch as bail-out funds would not be used to implement Title II of the Dodd-Frank Act, their appropriation would not be inconsistent with section 214 of that act, although a return to bailouts rather than bail-ins could effectively render Title II a dead letter.

The FDIC, in its “orderly liquidation” of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank that began in March 2023, declined to use its authority under Title II to expropriate any of those banks’ uninsured deposits to help the FDIC provide insurance to those banks’ FDIC-insured deposits. The FDIC’s decision not to expropriate uninsured deposits generated public complaint.

However, the FDIC’s reason for not expropriating uninsured deposits in SVB and Signature Bank seems self-evident and underscores limitations on the FDIC’s implementation of Title II of the Dodd-Frank Act.

Had the FDIC expropriated uninsured deposits in those banks, then a non-negligible proportion of the nearly half of US bank deposits that are not FDIC-insured might have left the US banking system for some safer haven. That could have threatened US economic stability by inducing a large and sudden contraction of bank lending, hence of the money supply, and hence of non-financial economic activity.

If, as it seems, the FDIC cannot prudently expropriate uninsured deposits of banks in FDIC receivership pending liquidation, then its resources for making good on its commitment to insure other deposits are limited to its own relatively tiny DIF, the equity and debt securities of the firms in receivership, and assessments levied on other financial firms.

Nothing guarantees that these resources will prove adequate, in the event of a systematic financial crisis, to obviate the FDIC’s asking the President to ask Congress to appropriate funds for another financial-system bailout like that of October 2008 – especially if the financial industry resists new or increased FDIC assessments.

Consequently, a third novel aspect of any 2024 financial crisis is that although, as in 2008, it may occasion an urgent demand by the President and Wall Street for another large bailout of the again-insolvent US financial industry, this request may come as a surprise to many voters and Congress members who have been led to suppose that Title II of the Dodd-Frank Act has lastingly obviated such bailouts by authorizing the FDIC to conduct bail-ins.

Thus, if this debt bubble is not different from 2008 in its unhappy ending, it will be different in the happy but untrue reason for which its unhappy ending was unexpected: widespread hope that a large financial sector default crisis could be ended by FDIC expropriation of uninsured deposits in failed banks or of assets of still-solvent financial firms will have been shown to be ill-founded.

So how might the House Republican Congress best respond to a 2024 bailout request? Any US financial crisis in 2024 bad enough to induce President Biden to take the politically perilous action of asking Congress to appropriate funds for another bailout of the US banking system will render Americans more receptive than ever before to novel notions about how such bailouts might lastingly be obviated.

The 2008 taxpayer bailout of the rich and systematically corrupt US financial elite was so widely and intensely disliked by Americans that it spawned the Dodd-Frank effort to obviate such bailouts in future. If the Dodd-Frank bail-ins fail to obviate another similar bailout only 16 years later, then Americans will be even more desperate to find some way to obviate such bailouts lastingly.

If this session of Congress is asked to appropriate funds for another large financial system bailout, then the Republican Caucus of the House of Representatives, comprising a majority of that chamber’s members, will be particularly desperate for a means of lastingly obviating banking system bailouts. Only by finding some plausible means of doing that can the House Republican Caucus escape from the political dilemma in which it will find itself if this session of Congress is asked for a banking system bailout.

If the House Republican Caucus refuses to appropriate funds for a financial-system bailout needed to mitigate a foreseeably large and rapid incipient economic contraction being precipitated by a financial-sector default crisis, then the preponderance of public blame could shift from the Democrats to the Republicans. In arguing for such blame-shifting, the Democrats would have the overwhelming support of US financial, corporate, academic and media elites.

In addition, one could hardly overstate the temptations that the financial industry can offer to legislators who must fund re-election campaigns in a country where neither campaign contributions nor campaign spending can be restricted because the Supreme Court has ruled that money is speech.

On the other hand, another banking system bailout would be anathema to the increasingly populist and working-class voters who dominate the Republican Party’s primary elections.

Absent some novel and unprecedently persuasive reason to think that this banking system bailout will be the last banking system bailout, populists will oppose it as corporate welfare perpetuating a pseudo-democratic oligarchy that has impoverished American workers for decades in its pursuit of cheap foreign labor by free trade and immigration.

Moreover, the affections of populist voters, if alienated by the support of another bank bailout, might prove past the power of campaign spending to regain.

Only by conditioning House Republicans’ support for another banking-system bailout on prior implementation of measures that would undoubtedly make that the last banking system bailout could the House Republican Caucus avoid blame for not mitigating an incipient economic contraction without alienating the populist voters who dominate Republican primary elections.

A solution to this dilemma is readily available and seems not only politically expedient but good for everyone in both the short and long terms. It also entails no additional government spending.

The third and last part of this three-part series will describe that solution, which, although conceptually novel, is easy to understand and is based on widely-accepted financial and institutional economics theory. It is to enable private conversions of banks into a better kind of financial firm that is less prone to default and need no government insurance of its depositors.

A financial sector made up of such firms, rather than of banks, would suffer fewer financial-system default crises and would not need government bailouts when it does experience such a crisis.

To induce the private sector to replace banks with such better financial firms, the federal government need only eliminate governmental obstacles to profitable private conversions of banks into such firms. The greatest governmental impediment to such conversions is FDIC insurance of bank deposits, which eliminates the greatest profit incentive for such conversions.