Uttar Pradesh: The state holding the key to India PM Modi’s re-election

57 days before

Geeta Pandey,BBC News

Ankit Srinivas

Ankit SrinivasAll eyes are on Uttar Pradesh, a state in northern India, known by its names UP, as the country votes to choose a new government.

The condition has almost four times as many people as it does, spread over an area roughly the size of Britain. It is India’s most popular position with an estimated 257 million residents, and it is the fifth-largest in the world if it were an independent nation after China, the United States, and Indonesia, and back of Pakistan or Brazil.

Only three states in India have the opportunity to cast ballots during the 44-day election process’s seven aspects. Voting ends on June 1 and results are announced on June 4.

So it should come as no surprise that Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s re-election campaign, which elects 80 MPs in the 543-member lower house of parliament ( the Lok Sabha ), is viewed as crucial.

” It’s generally said that ‘ the way to Delhi is through UP’ and a group that does well in the condition usually goes on to act India”, says Sharat Pradhan, senior columnist in the state capital, Lucknow.

” Eight of India’s former prime ministers”, he adds, “have represented the state and in 2014, when Mr Modi- originally from the western state of Gujarat – made his debut as an MP, he too chose UP”.

In the historic city of Varanasi, Mr. Modi occupied his seat in 2019 and intends to do so once more this year.

Getty Images

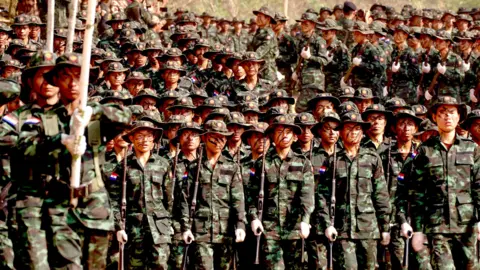

Getty ImagesSo Mr. Modi has taken a whirlwind state tour, holding roadshows, and speaking at rallies, sometimes seven in a day, to persuade voters to back his party. He’s set his Bharatiya Janata Party ( BJP) a goal of 370 seats- a party needs 272 to win.

In 2014, BJP won 71 seats in the state and in 2019, it got 62. This time, party leaders say, they’re aiming for 70 plus – even all of its 80 seats.

The maths, the opposition Congress party’s Gaurav Kapoor says, is simple –” a party that wins 70 seats here needs just 202 more to form a government”.

Earlier this month, when Mr Modi arrived in the city to file his nomination, accompanied by the state’s Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath, a saffron- robed Hindu monk- turned- politician, thousands of supporters gathered to cheer them on.

As their cavalcade made its way through the dusty streets of the ancient city, a truck carrying them was painted saffron, the color associated with the BJP.

As saffron-clad men and women raising slogans in support, Mr. Modi waved and held up a replica of the lotus flower, which was his party symbol.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt’s not just the BJP that’s eyeing the state regarded as “the biggest prize” in Indian election. The Congress, which was dominant in the state for four decades until it was edged out by local parties in 1991, is fighting here in alliance with the regional Samajwadi Party (SP). The alliance has also claimed that “we are winning 79 seats and have a fight in one”.

The results of the vote counting on June 4 are likely to reveal exaggerated claims made by both sides, but analysts claim that the state’s elections have always been won by the BJP. And the upbeat mood at Mr Modi’s roadshow reflected that self- assurance.

Most Varanasi residents in the audience spoke about the changes their city underwent in the last ten years, including the construction of new highways, the expansion of the Kashi-Vishwanath temple, and the restored Ganges Riverbanks.

Ambrish Mittal, a chemist, observes Mr. Modi’s procession from his shop along the route of the roadshow, saying that” the city roads are cleaner and the lengthy power cuts that plunged the city into darkness for hours are history.”

However, despite its political significance, UP continues to be one of India’s poorest states despite there having been some positive changes in recent years.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesGovernment data shows that millions more now have electricity, access to toilets and are using clean fuel compared to five years ago.

But UP still has the largest concentration of poor in the world – with 23% of its population recorded as multidimensionally poor even after tens of millions have been lifted out of poverty.

Every year, the state records tens of thousands of violent crimes committed against women, and it continues to garner headlines for cases in which defendants are politically powerful men.

And despite the fact that the BJP has been in power in UP for seven years and has also ruled the state for seven years, opposition parties have taken advantage of them and raised them at their campaign rallies.

Opposition leaders claim that the BJP’s record-breaking turnout at their meetings is a result of voter dissatisfaction with the BJP.

Abhishek Yadav, a leader of the Samajwadi Party youth wing and a prominent campaigner for his party, recalls that “up until a few weeks ago, the state’s election had appeared to be a one-sided contest with the odds stacked against us.”

He thinks that the opposition’s campaign has accelerated as unemployment and price increases have become major issues.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe state’s governor claims that there has been a significant investment spurt and that there has also been a revival of the industry, but Congressman Gaurav Kapoor claims that the government has alienated many voters by failing to create any new jobs or create new industries.

” Temples are Mr. Modi’s new industry. Hotels, restaurants, and other aspects of religious tourism are the only businesses in the state that have advanced since Post-Covid. But the youth want jobs”.

Ashwani Shahi of the BJP, however, blames opposition parties for everything that’s wrong with the state.

” In 2017 when the BJP won UP, we inherited a state which was poor, had high rates of illiteracy and unemployment. We have begun to alter that.

However, it takes time to lift people out of poverty. I think By 2029, we’ll be able to take 90 % people out of poverty.”

Mr. Modi’s support for the BJP will continue to win over Uttar Pradesh and the rest of India, despite Mr. Shahi admitting there is some anti-incumbency.