DBS’ chief data and transformation officer on ‘human’ AI in banking | FinanceAsia

Speaking to FinanceAsia at the 2024 Singapore Fintech Festival, Nimish Panchmatia, chief data and transformation officer at DBS, described how artificial intelligence (AI) could evolve beyond optimising individual tasks in banking,

Panchmatia noted: “Today, a lot of people are focusing on what I would call user-centered AI, but if you lift this up to the next level, is human-centred AI.”

This shift, Panchmatia explained, isn’t just about streamlining processes, but about building AI models that actively support customer well-being, financial literacy, and a positive societal impact

Going deeper into this human-centred AI (HCAI), IBM in a recent paper explained, “adhering to the core value that “human + AI” is better than either one individually, novel user experiences can be. developed that foster human-AI collaboration”.

HCAI is an emerging discipline and Panchmatia believes it is increasingly important for the banking sector. With AI-driven tools like virtual financial advisors and personalised education modules becoming more common, banks can reduce the transactional feel of interactions and establish themselves as partners in their customers’ financial journeys — a shift expected to drive stronger customer retention than models based solely on service speed or product sales.

Panchmatia also discussed adaptive feedback loops, which refine customer insights to continuously improve AI models.

For example, if a customer is given a “nudge” (such as an instalment option for a large purchase) and chooses not to engage, that feedback helps adjust future interactions.

“If you got a nudge and didn’t act, this went back into the model to say, ‘Okay, why didn’t this customer engage?’” he explained. By continuously learning from customer behaviour, banks can anticipate needs more accurately, aligning with the industry-wide shift toward hyper-personalised services.

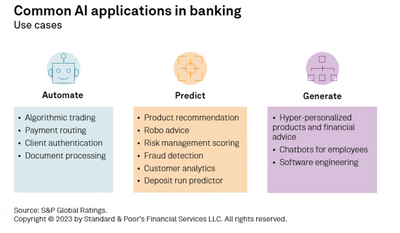

According to a 2023 report by S&P Global, the potential for the new AI to reshape banking is vast with below being some common AI applications in banking.

The McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) estimates that across the global banking sector, generative AI (Gen AI) could add between $200 billion and $340 billion in value annually, or 2.8% to 4.7% of total industry revenues, largely through increased productivity.

In terms of commercial priorities, Panchmatia explained how DBS builds its AI models around customer understanding. The bank uses a variety of methods, including surveys and sophisticated anthropology studies, to gather insights. “We sit down with client groups and observe,” Panchmatia said. By understanding customer needs before making decisions, the bank can ensure that AI-driven offers are relevant and beneficial.

The human angle of transformation

A successful transformation requires looking at all the components—technology, people, and processes—and understanding their collective impact, according to Panchmatia.

“What does this mean for the people in the organisation? What does it mean for the tech stack? What does it mean for the customers, the regulators, and any other stakeholders?” Panchmatia emphasised the importance of stakeholder mapping, assessing both potential successes and failures.

It’s through this holistic approach that banks can find the right balance between technology and people.

He stated, “If you change your branch system… is it a big tech project? Yes. Is it a bigger people project? For sure.”

Data responsibility

With AI becoming a standard feature of banking, the question of data ethics has risen to the forefront. Banks are increasingly tasked with managing not only structured data but also unstructured information.

In the finance industry, unstructured data can be found in various forms such as emails, social media posts, news articles, customer reviews, legal documents, and multimedia files. Unlike structured data, which is neatly organised in tables with a predefined format, unstructured data is not systematically arranged. It often consists of large amounts of text or multimedia content, making it more challenging to analyse and interpret.

With the rise of unstructured data comes an increased risk of misinterpretation, requiring clear guidelines to ensure responsible use.

At DBS, a protocol known as “P.U.R.E” governs this process. This structure reflects a growing industry-wide movement toward transparency, especially as more countries tighten their data regulations.

“Whatever you do must fit all these (P.U.R.E) parameters,” Panchmatia explained, emphasising that “the unsurprising and easy-to-explain part (in P.U.R.E) became a little more dynamic” when working with unstructured data.

Globally, banks are establishing similar frameworks to foster transparency and accountability in AI applications, aligning with regulatory shifts that prioritise customer privacy.

In Singapore, where DBS is headquartered, stringent data privacy laws require financial institutions to be meticulous about data governance. In June 2023, the Monetary Authority of Singapore released a toolkit for the responsible use of AI in the financial system called the Veritas Toolkit version 2.0 that will help financial institutions (FIs) carry out the assessment methodologies for the Fairness, Ethics, Accountability and Transparency (FEAT) principles.

Implementation of data integrity

In terms of data, Panchmatia explained that it is unsurprising for both the users who are handling it and the customers who are receiving it. Customers don’t have to question why they’re receiving certain information. “If you come to me and say, – why did you send me this notification – I need to be able to explain this to you.”

From a technical perspective, having the right tools and infrastructure in place for data is crucial, shared Panchmatia.

“If you’re going to build the model right, you’ve got to register it first.” This ensures accountability and traceability, allowing data management to kick into the workflow efficiently. If the necessary steps aren’t followed, such as completing a proper assessment, data cannot be used effectively for model training or testing.

The importance of oversight cannot be understated, either. “We have a senior committee in the bank that ensures that data initiatives align with the company’s strategic objectives and risk appetite. It’s not just about purchasing the latest tools—it’s about being thoughtful and deliberate in how data is handled across the organisation.”

Pace of change and societal impact

Looking to the future, AI’s rapid pace of development requires banks to build flexibility into their systems.

Panchmatia noted, “What was really novel eight months ago is now old school,” illustrating the speed with which AI advancements are transforming the landscape. This ongoing evolution is prompting banks to make continuous updates to their AI frameworks.

Statista predicts the banking sector’s spending on generative artificial intelligence (AI) to surge to $85 billion by 2030, with a remarkable 55.6% compound annual growth rate.

Elaborating on the scale of AI in DBS, Panchmatia shared some numbers.

For example, DBS has delivered over 370 AI/machine learning use cases spanning customer-facing businesses and support functions, and 1,500 AI/ML models to date (as of November 2024). It has also managed to compress time to value from 12 to 15 months down to two to three months, with the goal is to bring it down further to two to three weeks over the next few years; the bank said it has delivered a tangible economic impact of over S$370 million ($276.5 million) in 2023, S$700 – 800 million in 2024, and projected S$1 billion in 2025, working on its AI industrialisation approach.

Beyond technical agility, banks are grappling with the societal impacts of AI, particularly in terms of workforce transformation. While automation may streamline certain functions, new roles requiring specialised skills in AI and data analytics are emerging.

“It’s important to consider societal impact,” Panchmatia emphasised, adding that while AI might replace some roles, it will create others requiring upskilling and reskilling.

Beyond AI

Meanwhile, emerging technologies such as quantum computing and blockchain interoperability are also poised to expand the capabilities of banking AI. Quantum computing, with its potential to enhance complex risk assessments and fraud detection, is being tested through proof-of-concept initiatives in leading banks.

“We are doing some POCs with quantum,” Panchmatia explained, though he noted that large-scale banking applications may still be a few years away.

Blockchain’s progress hinges on interoperability; should these issues be resolved, decentralised finance (DeFi) could become a viable option for more banks, according to him.

¬ Haymarket Media Limited. All rights reserved.

.jpg)

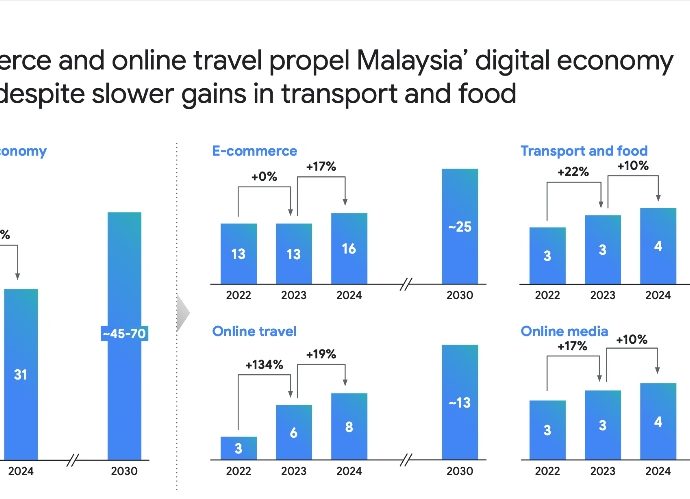

Meanwhile, Farhan Qureshi ( pic ), country director for Google Malaysia said:” We have been seeing a consistent strong growth of Malaysia’s digital economy and this year is another strong testament of the potential of Malaysia’s digital economy. With the region’s focus on AI, it’s encouraging to see the country’s leaders are putting AI and semiconductors in the country’s priority list”.

Meanwhile, Farhan Qureshi ( pic ), country director for Google Malaysia said:” We have been seeing a consistent strong growth of Malaysia’s digital economy and this year is another strong testament of the potential of Malaysia’s digital economy. With the region’s focus on AI, it’s encouraging to see the country’s leaders are putting AI and semiconductors in the country’s priority list”.