China’s population has started to decline and this has set off a Pavlovian negative reaction – via the news media – of the sort that we have seen before in the case of Japan.

Reuters warns that the news “sounds alarm on demographic crisis.” CNN predicts that the “impact will be felt around the world”, will act as a “drag on growth” and “could threaten China’s ambitions of overtaking the United States as the world’s largest economy.”

Even if some of the dire prophecies are accurate, however, the population decline will also make automation an absolute necessity – as has happened in Japan. It will widen China’s already large lead in the deployment of industrial robots and the industrial internet of things, helping to create an enormous market for service robots.

This process is already well underway. Over the past decade, installations of industrial robots in China have increased by 10.7 times, according to the International Federation of Robotics (IFR). Compare that with 68% growth in Japan, 67% growth in the US, 20% growth in Germany and 19% growth in South Korea.

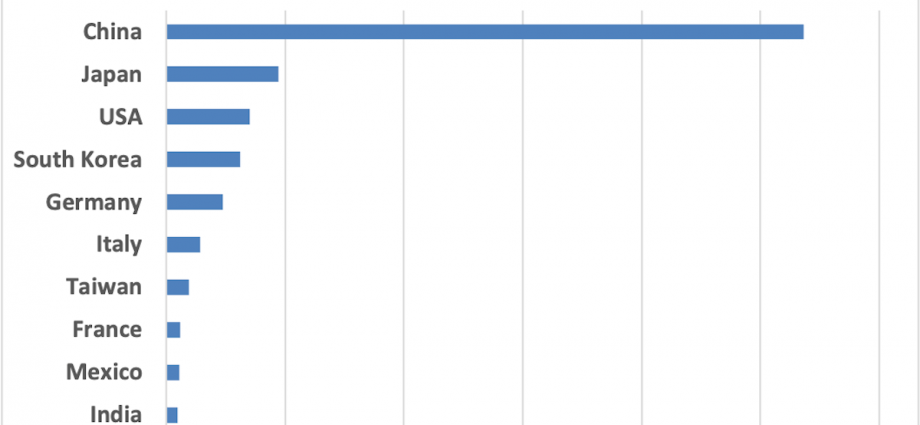

In just a few years, China has become the world’s largest user of industrial robots by a very wide margin. In 2021, China accounted for 52% of total worldwide installations. Trailing far behind, Japan accounted for 9%, the US for 7%, South Korea for 6% and Germany for 5%. Viewed by region, Asia accounted for 74% of the total, Europe for 16% and the Americas for 10%.

At the end of 2021, the total worldwide installed base of industrial robots was almost 3.5 million units – with more than one million, or close to 30%, deployed in China. That compares with 12% in Japan, 10% in South Korea, 9% in the US and 7% in Germany.

China has also become one of the world’s most intensive users of industrial robots. Data for 2021 shows China ranking fifth in robot density, which the IFR calculates as the number of industrial robots in operation per 10,000 factory employees. South Korea ranked first. The US ranked ninth. Five years ago, the US ranked seventh and China ranked 23rd.

Who makes all these robots? The IFR does not provide robot production data, but information from other sources indicates that four companies – ABB, Fanuc, Yaskawa and Kuka – may account for close to three-quarters of the global market for industrial robots while Japanese companies alone account for half or more.

ABB is a Zurich-based European multinational, Fanuc and Yaskawa are Japanese and Kuka is a German company acquired by Chinese electrical appliance maker Midea in 2016. To see why Midea bought Kuka and what it means for Chinese manufacturing, watch this video:

In its Industrial Robots market report of May 2022, Fortune Business Insights profiled 10 key industrial robot makers:

- ABB (Switzerland)

- Comau (Italy)

- Denso (Japan)

- Fanuc (Japan)

- Kawasaki Heavy Industries (Japan)

- Kuka (Germany/Chinese-owned)

- Mitsubishi Electric (Japan)

- Nachi-Fujikoshi (Japan)

- Omron (Japan)

- Yaskawa (Japan)

The Association for Advancing Automation, a North American industry group, also counts Epson (Japan), Staubli (Switzerland) and Universal Robots (Denmark, American-owned) as industry-leading companies.

There are no US companies on these lists, but Rockwell Automation is a top supplier of industrial automation control equipment and Cognex is a leader in machine vision.

There are no Chinese companies on the lists either, but there are many Chinese industrial robot makers working their way up the value chain from simple handling robots full of imported components to more sophisticated machines with higher local content.

They are receiving full support from China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) and other government organizations, which aim to double the nation’s robot density by 2025.

Meanwhile, 121,000 professional service robots were sold in 2021, according to the IFR. That was 23% of the total number of industrial robot installations.

Service robots are often smaller than industrial robots and more specialized, but not necessarily less sophisticated than industrial robots. In 2021, their primary applications were transportation & logistics, hospitality (retail and food industries, etc), medical-healthcare, cleaning, agriculture and inspection-maintenance. Compared with 2020, service robot sales increased by 37% while industrial robot installations were up 31%.

Making service robots are hundreds of companies – more than 70% of them small and medium-sized enterprises with 200 or fewer employees, according to IFR data. The largest number can be found in the US followed by China, Germany, Japan, France, Russia, South Korea, Switzerland and Canada.

According to the MIIT, service robots currently account for more than 35% of the overall Chinese robot market, a high number that reflects lower barriers to entry and the size of the addressable market.

Service robot vendors do not have to contend with the enormous economies of scale and customer relationships established by the leading vendors of industrial robots, and there are more potential customers in China than in any other market.

The IFR identifies demographic decline – the looming shortage of labor – as a key driver of robot demand for the next several years. In China, that will be compounded by rising wages, which have already caused companies to move labor-intensive assembly operations to Southeast Asia.

Some outside observers see this as a negative for China’s status as the workshop of the world but a rising standard of living is not negative if you can move up the value chain.

The (slightly) old Chinese factory:

The new Chinese factory:

China’s birth rate has been remarkably low recently. (For details, see “China’s demographic timebomb starts ticking down” by Asia Times’ Jeff Pao and “China’s population shrink in big picture perspective” by Xiujian Peng.) But fertility is below the replacement level in all of the big markets for robots.

About 20 years ago, I visited an industrial trade exhibition in Hamburg, where I met a young Chinese entrepreneur who had come to Germany for a year to study the language and industrial policy.

He told me that the Chinese did not want to be a low-wage nation doing assembly work for others. In the future, he said, China would be a first-rate manufacturing power like Germany.

Since then, he and many others like him, supported by a well-planned industrial policy, have made it happen. And now, as China’s population and number of people in the active workforce decline, the incentive to automate will only increase. The Chinese industrial juggernaut has a new engine.

Follow this writer on Twitter: @ScottFo83517667