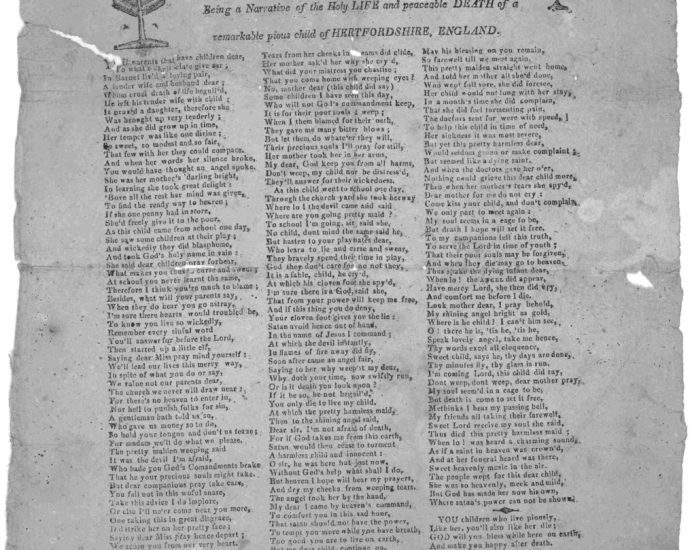

Drug traffickers smuggling crystal meth past South East Asia security – UN

EPA

EPADrug traffickers have found new ways of smuggling crystal methamphetamine, known as ice, out of South East Asia to high-paying customers outside the region, according to a UN report.

Criminal gangs are moving more drugs by sea to evade land patrols in Thailand and China, making them harder to spot.

They have learnt “to anticipate, adapt and try to circumvent” law enforcement, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime said.

The ice is sold in Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand.

The huge trade in methamphetamines and other illegal drugs, which mostly flow from super labs in parts of Myanmar, is also showing no signs of slowing down, the UN agency warned.

Shan state in Myanmar is home to what many believe is the world’s largest meth trade. Traffickers ship the drugs out through the borders of Laos, Cambodia and Thailand, an area known as the Golden Triangle.

“In 2022, we saw them work around Thai borders more than in the past,” said Jeremy Douglas, the UN agency’s regional representative.

“Traffickers have continued to ship large volumes through Laos and northern Thailand, but at the same time they have pushed significant supply through central Myanmar to the Andaman Sea, where it seems few were looking.”

The meth comes in two main forms: pills known as yaba or highly addictive crystal meth (ice).

In recent years, both Thai and Chinese police, backed by neighbouring forces, have stepped up operations in the Golden Triangle.

Criminal gangs use Thailand as a transit country to get high value crystal meth to a third country such as Australia or New Zealand where the street value of the drug can be 10 times higher than in Bangkok.

High volumes of Myanmar meth is also making its way into Bangladesh and India, according to the report.

In the last year, Thai and Chinese authorities have seen a significant drop in drug seizures.

Police across East Asia and South East Asia seized nearly 151 tonnes of methamphetamines in 2022, down from a record of 172 tonnes in 2021.

However, the price of 1kg (2.2lbs) of crystal meth is at an all-time low, which suggests that supplies are still high.

Officials believe criminal gangs have found ways to “diversify” their network and move the drugs using alternative maritime routes. Thai drug enforcement agents are managing to intercept some of the supplies at sea.

Earlier this week, after a four-month operation following drug smugglers, Thai authorities seized more than 900kg of crystal meth from a trawler in the Gulf of Thailand, about 32km (20 miles) from the tourist island of Samed. Six crew members were arrested in the operation.

Officers said the drugs would have been transferred from the small Thai boat to a bigger trawler which would have likely taken the drugs to Australia.

Authorities across the region also seized a record 27.4 tonnes of ketamine in 2022, which is an anaesthetic misused as a recreational party drug. That’s up 167% on 2021.

The report highlighted one ketamine laboratory in Cambodia which they said was capable of “industrial scale” production.

It also expressed concern that Cambodia had become “a key transit and to some extent production point for the regional drug trade”.

“The discovery of a series of clandestine ketamine laboratories, processing warehouses, and storage facilities across the country has set off alarm bells in the region,” the report said.

Related Topics

-

-

26 August 2022

-

Singaporean bus driver charged with misappropriation of diesel in JB

JOHOR BAHRU: A Singaporean bus driver pleaded not guilty in a Johor Bahru court on Friday (Jun 2) to the charge of misappropriating about 500 litres of diesel, a controlled item in Malaysia. Benjamin Low Yong Pang, 24, was charged with breaching the Control of Supplies Act for possessing the diesel onContinue Reading

Are the rich more intelligent? Hereâs what science says

From White Lotus to Succession, there’s high demand for television dramas about the super rich. The characters on these shows are typically portrayed as entitled, hollow and sad. But they aren’t necessarily depicted as unintelligent. So are rich people rich because they are smart?

In the middle of a cost-of-living crisis, this question goes beyond scientific curiosity and touches something deeper.

If people’s net worth were only the consequence of their intelligence, the gigantic wealth gap we see in our society might be perceived as less intolerable – at least by some. Inequality would be the price to pay for having the smartest lead us all to a better future.

There is little doubt that intelligence contributes to one’s economic and professional success. Take self-made billionaires Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and Ray Dalio, just to name a few. It would be surprising if top innovators in advanced fields such as tech and finance turned out to be average.

In fact, intelligence is the best predictor of both educational achievement and work performance. And academic and professional success is, in turn, a fairly good forecaster of income. But that’s not the whole story.

Not all highly intelligent people are primarily driven by a desire for wealth – they often have a thirst for knowledge. Some may instead opt for comparatively less well-paying jobs that are more intellectually rewarding, such as architecture, engineering or research.

A recent Swedish study showed that cognitive test scores of the top 1% of earners were not significantly different to the scores obtained by those who earned slightly less.

But to what extent does intelligence boost wealth? Before diving into the evidence, we must clarify what researchers mean by “intelligence.” Intelligence can be defined as the ability to perform a wide range of cognitive tests successfully.

And these seem to be linked. If someone is good at resolving a particular cognitive test, they will probably perform well in other cognitive tests too.

Intelligence is not a monolithic trait, though. In fact, it consists of at least two broad constructs: fluid intelligence and crystallized intelligence. Fluid intelligence taps into core cognitive mechanisms, such as the speed of processing stimuli, memory capacity and abstract reasoning. Conversely, crystallized intelligence refers to those skills developed in a social environment, such as literacy, numeracy and knowledge about specific topics.

This distinction matters because these two types of intelligence develop in different ways. Fluid intelligence can be inherited, cannot be boosted and decreases fairly quickly with age. By contrast, crystallized intelligence increases throughout most adulthood and starts declining only after about 65 years.

But fluid intelligence helps build up crystallized intelligence. Fluid intelligence represents the brain’s capacity of acquiring and elaborating information. Crystallized intelligence is, to a large extent, acquired information.

This means that if your reasoning skills are sharp, then you will process new information quickly. You will integrate novel information with old information accurately. Ultimately, this will speed up learning of any discipline and contribute to your academic and financial success.

Education is a factor

That said, innate capabilities are not the only thing that matters. Another significant factor is education.

A quantitative review has established that the more years of schooling, the higher students’ intelligence scores. Crucially, these improvements stem from training in specific skills rather than enhancing general intellectual ability. So school teaches you useful stuff for both professional success and performing intelligence tests.

Unsurprisingly, education in turn is affected by family socioeconomic status. For example, expensive schools and private tutors provide the student highly efficient personalized instruction. Access to top quality education may therefore make a huge difference in future income.

Of course, the influence of family socioeconomic status on wealth does not operate solely through education. Inheritance and networks are among the most obvious mechanisms. This is particularly true for entrepreneurs, whose investing potential and connections are fundamental for business success.

The role of luck

So intelligence, education and socioeconomic status all affect one’s income. However, these factors alone are unlikely to fully account for the individual differences in wealth. In fact, a recent study suggests that luck exerts a significant impact.

This study highlights that the statistical distribution of wealth differs from the distribution of intelligence. Intelligence is “normally distributed”, with most individuals being around average. By contrast, wealth follows a “pareto distribution”, a formula which shows that 80% of a country’s wealth is in the hands of only 20% of the population.

Intelligence versus wealth distribution

This means intellect alone cannot account for the disproportionate disparities between rich and poor in our society.

The study does not downplay the role of intelligence (or talent in general). A fine intellectual ability improves the chances of getting rich. Nonetheless, intelligence is no guarantee of getting rich. Furthermore, a series of fortunate events can clearly turn unremarkable individuals into high earners.

That is, when it comes to getting rich, intelligence is neither sufficient nor necessary. But it does help.

“I’d rather be lucky than good,” says the character Chris Wilton (Jonathan Rhys Meyers) in Woody Allen’s film Match Point. In the light of the evidence we have just reviewed, he may be right.

Being born into a wealthy and highly educated family is a fortunate event. Likewise, random strokes of luck (like winning the lottery) do not come from years of hard work. We may even push the argument a bit further and conclude that being intelligent is a form of luck itself.

Many things that contribute to achieving financial success are beyond our control. Most, if not all, extremely wealthy people have been blessed by Lady Luck somehow.

Conversely, making the most of what luck brings us certainly matters. Granted, a good deal of individuals merely cash in the benefits of inherited privilege.

Regardless, many small and big fortunes stem from an intelligent use of the resources we are lucky to have been gifted with – whether they are intellectual, educational or socioeconomic.

Giovanni Sala is Lecturer in Psychology, University of Liverpool and Fernand Gobet, Professorial Research Fellow of Psychology, London School of Economics and Political Science

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

A life for children’s rights

Children make up a third of the world’s population. One might wonder what would happen if they had self-representation in global politics.

“A society that welcomes the voices of children will certainly be a bit noisier. As if adults weren’t noisy enough,” joked child rights advocate Amihan V. Abueva. “But maybe with some louder noise from the younger ones, we could find more sense and better solutions.”

From the Philippines, Abueva has been a pioneer in her field for more than three decades. This week marked International Children’s Rights Day on 1 June, which the Southeast Asia Globe commemorated by walking through her pivotal work across the region and world in an extensive interview.

A key member and former president of the Bangkok-based child protection network ECPAT International, Abueva played a major advocacy role for stopping child prostitution in the global sex tourism of Southeast Asia.

Beyond that, Abueva has long been a vocal proponent of the right of children to participate in society, especially in policy-making about child welfare. She previously served as the Philippines’ government representative to the ASEAN Commission for the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Women and Children (ACWC) and has worked to encourage input from youths and children.

Abueva was born in the Philippines and raised during the authoritarian regime of President Ferdinand Marcos Sr. In those years, she overcame several obstacles to become a rights defender, but the real turning point in her work as a children’s advocate wasn’t until after the end of the Marcos dictatorship in 1986.

Soon after the restoration of democracy, she gave birth to a child.

“Then it was when I became a breastfeeding advocate and got more serious about children’s rights,” Abueva said. “I have never left.”

That was 1988. The next year, the UN adopted the first children’s rights international treaty, the Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). Abueva, who started her activism in the Marcos years, and her team successfully lobbied the Philippine Senate until it signed and ratified the treaty in 1990.

The UNCRC is now the most widely ratified human rights treaty in history, adopted by 196 nations, including all Southeast Asia countries.

Although that was a big milestone for the region, Abueva felt it wasn’t enough.

Through the years, while overseeing research on prostitution and tourism, she felt “it was really important to talk to the children themselves about it”.

In 1996, she embarked on a campaign to involve children in the first World Congress Against Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children in Stockholm. The event included representation from 122 governments and civil society organisations from around the world.

“I had a real uphill battle,” she said. “I insisted that children should be participating at the same level as adults, and I won.”

The planning committee accepted her plea and 16 children from the Philippines, Sweden, Brazil and Ghana participated in the congress.

That was just the beginning. From 2000 to 2008, hundreds of children from more than 20 countries were involved in international meetings. As children’s participation grew quickly, ECPAT worked along with other international organisations to facilitate the process and train adult participants to safely and effectively interact with the youths.

“Many people work for children, but they don’t know how to work with children,” she said.

Abueva wants to see even more child participation across all levels of governance, from domestic to international.

“When you help children to grow and develop critical thinking, they can become leaders for themselves,” she said. “It is our responsibility to accompany them. Especially in our society, which is not kind towards those who think critically.”

What does child participation mean in the context of Southeast Asia?

A concept we are seeing emerging now is children as human rights defenders. But, of course, it’s difficult in a region where even adult human rights defenders are at risk.

By using the term “human rights defenders”, children could find protection in already-existing international legislative standards. But the problem is how the state allows those rights. We have to help children to value peace and solidarity and so to help each other rather than become military-led.

Recognition of the children’s right to participate in Southeast Asia has been progressing at different levels. Thailand, Indonesia, Cambodia, Philippines, are more involved in child participation across the region, while others, such as Laos and Vietnam, are still trying to catch up. In Myanmar, we also have a big problem now. The military junta really endangers lots of children. We are still working with some groups there, but they have to be really careful. We are still trying to find safe ways for them to participate, for instance, through consultations with the UN.

Civil society organisations, government agencies and inter-governmental bodies have strengthened collaborative work to create safe spaces for children to express their views on matters affecting their lives. But aside from the various efforts of creating safe spaces for children, child participation is not just children receiving kits or food during an activity, it is not just children watching magic shows, or having activities to commemorate children’s month.

Meaningful child participation brings in children even at the planning stage, where children can raise what they think is the best way for them to celebrate the children’s month, what programs, projects or activities are appropriate or are needed by them and their peers, and how the activities should be implemented that will ensure child-friendly approaches and tools. Another important aspect of meaningful child participation is getting the children’s feedback on the activities and how they can be further improved in the future.

Allowing children to speak and make decisions, even as simple as letting them decide the colour of shirt to wear, helps them develop important life skills like problem-solving, critical thinking, and communicating.

What programs and activities are available for children to participate in key decisions at a community or national level?

At the national level, civil society groups are advocating for more meaningful child participation in existing or current mechanisms.

For example, in the Philippines, the local government units are mandated to create a Local Council for the Protection of Children at the village, city or municipality and province levels. Children representatives are among the members of the council. Consultations with children are being conducted at the village level. The team is also in charge of promoting and ensuring a safe environment for children and overseeing the government’s action on the topic.

Across the region, efforts to organise children and youth groups are also multiplying because we have to remember that children are not just passive recipients of services, victims, or survivors, but they are also active agents of change.

In issues like climate change, children are already taking action in simple ways that are also relevant in their own community. In the UNCRC monitoring and reporting, children are actively participating in preparing the reports submitted to the Committee on the Rights of the Child.

At the regional level, there is the ASEAN Children’s Forum (ACF), which is conducted every two years. During this regional meeting, children talk about issues that affect their lives and their peers. We also conduct a regional childrens’ meeting annually. We gather children from the communities where our member organisations work. In addition, we conduct consultations with children for our strategic plan.

In 2019, we organised the Asian Children’s Summit for the first time. It was a way to try to bridge the whole of Asia. So we had children from East Asia, Southeast Asia and South Asia. The kids discussed four main themes, namely the right to help the environment, digital safety, children and the in the context of migration and violence against children and we asked them to develop what they wanted to say about this.

That event especially demonstrated that children have so many ideas and that we need everybody to be working together.

We value children’s voices in our work and we learn a lot from them and because of this, we are able to do our work better.

What are some of the main challenges in this field?

First, the participation rights of children need to be fully understood by all stakeholders. It is not just simply listening to children when they talk. Article 12 of the UNCRC talks about “giving due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of children”. It is active listening for adults and taking action based on the views of children. At the same time, adults have the responsibility to explain to children why some of their views could not be considered.

Meaningful child participation can be consultative, collaborative or child-led. These three approaches are equally important.

Another problematic thing in Asia is that there is the process behind the [ASEAN Children’s Forum], which is organised by the ministers for social welfare and development and regional working groups. The ones who really get the work done here are senior officials in the end, which is not really the point of a children’s forum, is it?

We [children’s rights practitioners] don’t know who actually listens to what the children said and what they do with the children’s opinions afterwards. There’s been an attempt to revise the terms of reference, but I’m not sure whether that’s already been changed or not.

Another major issue now is that children are the first ones to lose their voice when civic space shrinks and states impose stronger restrictions. That is what’s happening in Myanmar. But in the Philippines, things are also not going too well for children.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, two teenage girls broke the curfew rules and two policemen caught them and took them to the beach. They sexually molested one and raped the other. Following the event, one of the girls went to report the case to the police in a neighbouring town but in addition to being denied police protection, on the way home she was ambushed and shot dead.

Our work is to explain to the kids that when you are abused go to the police and report the violence. But cases like this really break everybody’s trust. If even the authorities don’t respect children, we are in big trouble.

Our role as child rights defenders is to ensure that the children’s voices are heard as loudly as possible.

What are your hopes for the future of children’s rights in Southeast Asia?

One day, a girl from Pakistan and her Indian friend came to me and said: “Grandma Ami, when you talk about our right to a healthy environment, don’t think only in terms of physical health, you have to also talk about mental health.”

And I was really taken aback because it was 2019. At that time, there wasn’t that much being said about the mental health of children. This was pre-pandemic. I really thought they had a point. Mental health was and is a big problem and I realised that thanks to two children speaking up to me.

This is exactly what I hope for the future; that adults value children’s opinions. When we embrace their participation, we need to value them for what they are now and for what they will be in the future.

Children’s rights are everybody’s business.

US has more military experience, but China has infrastructure to grow capabilities at a faster rate: Analysts

They were speaking to CNA on the first day of this year’s Shangri-La Dialogue, which takes place from June 2 to 4 in Singapore. It involves 41 countries, with Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese delivering the keynote address on Friday.

BOLSTERING MILITARY CAPABILITIES

Mr Ankit Panda, Stanton Senior Fellow in the Nuclear Policy Program at Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, said an upward trend in military capabilities has been observed in recent years in Asia and Southeast Asia.

“With the war in Ukraine, in particular, policymakers and defence chiefs are simply more attuned to the fact that inter-state conflict is not a thing of the past. It can very much happen in the 21st century and it can happen in Asia,” he told CNA’s Asia Now.

“So this, I think, is primarily driving continuing investments in advanced capabilities.”

He added that countries in the region, especially maritime states, are looking to strengthen themselves in the maritime domain, in order to patrol their territorial waters and protect their exclusive economic zones.

A long march: Chinaâs military-industrial espionage

This article is adapted from the authors’ new book, Battlefield Cyber: How China and Russia are Undermining our Democracy and National Security (Prometheus, August 2023, available for preorder here).

Recent revelations that Chinese state-sponsored hackers penetrated US critical infrastructure and have the ability to disrupt oil and gas pipelines, rail systems, and the US Navy’s communications in the Pacific theater should come as no surprise. China’s pursuit of digital dominance has been decades in the making.

Reveille for China’s planners was sounded in the early 1990s during the Gulf War, in which the United States and its allies effortlessly toppled Iraqi forces. The first conflict of the digital era demonstrated to Chinese strategists the critical role of information technology on and off the battlefield.

Chinese leaders watched with dismay as the American military routed and dismantled the Iraqi military in what is considered one of the most one-sided conflicts in the history of modern warfare.

Going into the first Gulf War, Iraq’s military was ranked fourth in the world – having ballooned to more than a million troops who had been trained on weapons financed by the West to fight its bloody eight-year war with Iran.

The Chinese military, although larger in headcount at the time, paled in technological comparison with the forces commanded by Saddam Hussein. At the time, China’s air force consisted of a few fighter jets, mostly of its J-7 model – an indigenously produced replica of the Russian 1960s-era MiG-21.

Iraq’s air force, by contrast, was made up of far more advanced fighters, such as the Russian MiG-29, and its planes were supported by advanced antiaircraft missile defense systems. Yet even those advanced weapon systems proved wholly ineffective against 1990s-era American technology.

“The Chinese looked at Iraq and saw an army similarly equipped as theirs with old Soviet weaponry, and they saw how quickly the Iraqis were taken apart,” says analyst Scott Henderson of the cybersecurity firm Mandiant. Henderson was with the US Army at the time, specializing in China.

“A lot of the ease of victory had to do with the information advantage,” he says. “The Chinese looked at that as a warning to them, but also an opportunity. The Chinese realized they did not have to compete with the US plane-for-plane and tank-for-tank. They could envision how they could get to a level playing field using technology, rather than building traditional weapons.”

China’s subsequent campaign of aggressive technology modernization has enabled a sprint to near parity with the United States.

Crucial to this achievement has been China’s centralized economic control – over not only state-owned enterprises but also formerly private-sector companies over which the Chinese Communist Party has now asserted de facto legal control through a series of national security, intelligence, and cybersecurity laws.

The government announces openly the technologies it wants to develop. It did so in its “Made in China 2025” plan and also has done so in its 14 consecutive five-year plans. The Chinese government supports domestic companies to become global leaders in these technologies.

To that end, the Chinese military and intelligence services turn over to those companies R&D secrets obtained through cyber activities and intellectual property theft. As a result, advanced military capabilities, based on the stolen designs, are rapidly developed and then flow to the People’s Liberation Army as part of the “military-civil fusion” that President Xi Jinping has declared.

The end goal of this process is to transform the PLA into the world’s most technologically advanced military by 2049, the 100th anniversary of Mao Zedong’s establishment of communist rule in China.

The fruits of this espionage-fueled modernization plainly have manifested themselves in China’s march toward naval superiority. Since the early 1990s, China has been transforming its navy into an advanced modern force capable of contending with the US Navy. According to the US Department of Defense, China’s current fleet comprises the largest navy in the world with 355 vessels.

In June 2022, the Chinese navy launched its first indigenously produced aircraft “supercarrier.” Named for China’s Fujian Province, this new supercarrier forms the cornerstone of China’s modern blue-water naval force. Before Fujian, the Chinese navy’s two seaworthy carriers were small carriers that used ski-jump-like devices to launch planes. They were based on a 1980s-era Russian Kuznetsov-class carrier.

The newly launched Fujian, at nearly 1,000 feet in length, is based on America’s recently launched USS Gerald R. Ford, as evidenced in Chinese propaganda photos showing the housings for Fujian’s four electromagnetic catapults – capable of launching the ship’s entire complement of aircraft in under an hour.

How China has been able to rapidly transform its Cold War-era ships to a modern and technologically advanced naval fleet can be found in a trail of digital breadcrumbs left in the networks of American companies.

As early as 2013, the Defense Science Board reported that more than 50 Defense Department system designs and technologies had been compromised by Chinese hackers. Prominently listed in its report were advanced aircraft designs and the electromagnetic aircraft launch system that recently was unveiled on the Fujian.

In 2014, the FBI arrested a Chinese national and permanent resident of Canada for his part in a six-year conspiracy that allowed Chinese hackers access to the networks of Boeing. In his 2016 guilty plea, Su Bin admitted to having enabled the hackers to steal sensitive military information – including information on the development of America’s latest carrier-based stealth fighter, the F-35. In total, the scheme yielded the Chinese government hundreds of thousands of flight-test documents pertaining to American naval aircraft.

Penetrations were not limited to fighter jets and carriers. In 2017, a Chinese hacking group was quietly probing the network of another defense contractor. Due to the sensitivity of the program, the US government redacted the victim company’s name in all official correspondence, except to verify that the company was working on sensitive programs for the US Naval Undersea Warfare Center. In the end, the Chinese hackers stole more than 600 gigabytes of data from the contractor’s system.

Charged with developing next-generation submarine technologies and weapon systems, the Naval Undersea Warfare Center is based in Newport, Rhode Island. It is the Navy’s focal point for all research, development, testing, and evaluation of undersea warfare capabilities ranging from autonomous submersibles to submarine communication systems to small modular nuclear reactors.

The unnamed contractor was secretly developing a supersonic anti-ship cruise missile capable of being launched from submarines. “Sea Dragon” – as the program was named – was scheduled for initial deployment on US submarines in 2020.

Considered a game changer by military experts, submarine-launched supersonic and hypersonic anti-ship missiles are incredibly difficult to shoot down and nearly impossible to evade.

But in early 2018, Chinese hackers penetrated the contractor’s network and stole the Sea Dragon plans. The technology is now included in China’s naval arsenal and will surely be fielded against the US Navy during any potential conflict.

Has the US come to grips with what it’s facing? The recent revelation by Microsoft of Volt Typhoon – a state-sponsored cyber actor based in China – indicates there remains significant work to be done.

Plugging the holes

As a warfighter during a storied career that spanned 39 years, US Air Force General Herbert “Hawk” Carlisle led combat aviators flying some of the most advanced weapon systems on the planet. Before retiring with four stars, Carlisle rose to become commanding general of the Air Combat Command – responsible for overseeing, delivering, and maintaining all Air Force combat assets, including more than 135,000 airmen, worldwide.

Carlisle knew what he was talking about when he wrote in a 2020 Defense Department report on threats to the US military’s supply chain: “Our military superiority is under direct attack from our most sophisticated adversaries – nations whose cyber actors continuously target the very industry that powers the US military’s technological advantage.”

After retiring, Carlisle served as the president of the National Defense Industrial Association – an organization that works with the defense industrial base, which consists of more than 300,000 companies, including major corporations such as Lockheed Martin, Boeing and Northrop Grumman as well as smaller companies.

In 2022, the association wrote in its annual report that the defense industry “faces sustained and increasing threats of intellectual property theft, economic espionage, and ransomware, among other security breaches. Data breaches, intellectual property theft and state-sponsored industrial espionage in both private companies and university labs are on an unrelenting rise.”

These warnings should be read as an SOS for US national security. For the first time, the US military can see clearly that it could be fighting an advanced Chinese adversary armed with weapons developed from stolen American technology.

Yet the Pentagon has been unable to focus sufficient attention on the threats that face its suppliers due to limited authority and resources to identify possible Chinese penetrations in its supply chain. While the Defense Department and the defense industrial base stumble through the years-long implementation of effective cyber safeguards, Chinese cyber actors continue to pillage America’s defense intellectual property.

It is critical for Americans to understand that the centralized party-state of China is undermining and exploiting the United States’ current defenses against theft of military secrets and intellectual property. This alarming situation demands immediate and decisive action on two fronts.

Domestically, it is essential to bridge the longstanding libertarian divide between the public and private sectors. This will involve augmenting and enforcing cybersecurity regulations along the defense supply chain, cultivating an environment that supports cyber hygiene and the exchange of threat intelligence, as well as encouraging investment in the advancement and application of state-of-the-art security technology.

On the global stage, the United States and its allies must act assertively to hold China accountable for its cyber and corporate espionage, particularly when targeting defense technologies and critical infrastructure. Possible measures may include sanctions, international détentes and embargoes against Chinese corporations that benefit from the fruits of malicious cyber activities.

Furthermore, the global community needs to set standards of conduct concerning cyber-economic and industrial espionage. Such a collective effort would form a united front of nations ready to challenge China and impose penalties for its aggressive behavior.

As a naval officer, Michael G McLaughlin served as senior counterintelligence advisor for the United States Cyber Command, responsible for the coordination of Department of Defense counterintelligence operations in cyberspace. He is now a cybersecurity attorney and policy advisor in Washington, DC.

William J Holstein was based in Hong Kong and Beijing for United Press International and has been following US-China relations for more than 40 years. Holstein has worked for or contributed to top publications including Business Week, US News & World Report, the New York Times and Fortune. His nine previous books include The New Art of War: China’s Deep Strategy Inside the United States.

250,000 travellers departed Singapore via Woodlands, Tuas Checkpoints on Jun 1

TRAFFIC TO REMAIN HEAVY

Traffic is expected to remain very heavy at both land checkpoints with continuous tailbacks from Malaysia’s checkpoints for departing motorists, said ICA.

Those who wish to depart to Malaysia or enter Singapore via the land checkpoints by car or bus are advised to factor in additional waiting time for immigration clearance.

ICA also requested patience from travellers and that they should observe traffic rules, maintain lane discipline and cooperate with officers on-site when using the land checkpoints.

In a Facebook post on Friday afternoon, ICA said it had enforced the “no right turn” rule for drivers seeking to enter Woodlands Checkpoint from Woodlands Centre Road.

Drivers are to find alternative routes to Woodlands Checkpoint like the Bukit Timah Expressway or Woodlands Road, and are reminded to maintain lane discipline and cooperate with officers performing traffic control duties on site, it added.

Close to 1.4 million travellers crossed the land checkpoints over the Good Friday long weekend in March, with an average of about 350,000 crossings a day.

Drone strikes up the ante of Ukraine war

A wave of approximately 30 drones appeared in skies around the Russian capital, Moscow, on May 30. Though widely sensationalized as a major attack against the heart of the Russian government, they caused only minor damage, mostly to high-rise buildings.

These drones were not intended to cause major destruction. Rather, they were meant to send a message that Ukraine – which has not claimed responsibility for the strikes – has both the capacity and will to strike back at the capital of its enemy invader.

Although different in scale, this is not the first such strike against Moscow. In early May, Russia alleged that Ukraine had targeted President Putin with a drone strike, which Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, promptly denied.

And Ukraine is thought to have been behind a series of drone strikes against airbases in Russia’s Kursk, Saratov and Ryazan regions, up to 300 miles inside Russian territory.

More recently, the Russian defense ministry claimed that a Ukrainian drone attack on one of its spy ships in the Black Sea, the Ivan Khurs, had failed. There have also been drone strikes against Russian oil pipelines and refineries including near the Black Sea port of Novorossiysk, a crucial oil export hub for Russia.

Drone strikes are not the only way in which the war has come home to Russia. The Belgorod region, to the north of the Ukrainian city of Kharkiv, has seen a spectacular ground assault raid by the so-called Russian Volunteer Corps and Free Russia Legion (two Ukraine-based far-right Russian militia groups), which took the Russian military two days to repel.

Because of its strategic location as a training and staging ground, Belgorod has repeatedly come under attack. In October 2022, two gunmen killed 11 soldiers at a training ground, wounding a further 15.

The region has also been repeatedly struck by Ukrainian artillery, missiles and drones since the beginning of Russia’s invasion in February 2022. These strikes have become more frequent and intense in recent weeks.

Intensifying air war

The bigger picture that emerges from all this has two important dimensions. First, it suggests that at the moment, there is a lull in the ground war and an intensification of the air war. This comes after Russia’s Wagner paramilitary group finally captured the embattled city of Bakhmut on May 20.

The costs of the intensifying air war are particularly borne by Ukraine, which has endured daily waves of drone and missile attacks since then, including on its capital Kiev.

None of this has been a gamechanger for either side. If anything, it has demonstrated Russian vulnerabilities that expose the Kremlin’s version of the “special military operation” for what it is – a full-on war in which even the Russian capital is not safe from air strikes, let alone areas closer to the border with Ukraine.

But it has also made it easier for Kiev to lobby Western allies successfully for more military support, demonstrating the need for, and usefulness of, both air defense systems and advanced attack drones and missiles – such as the UK’s Storm Shadow missiles which, according to Ukraine’s Defense Minister Oleksii Reznikov, “hit 100% of their targets.”

The second dimension is that while the air war and protracted battle over Bakhmut have captured most media attention, Russia has dug in deep in the Ukrainian territories that it captured and now occupies. Defenses against an expected Ukrainian offensive have been massively fortified along the around 1,000 kilometers of frontline and along the beaches of Crimea.

But Russia is also digging in in other ways. On April 27, Putin signed a decree that forces residents in the occupied territories either to accept Russian citizenship or become stateless.

And at the end of May, the Russian president approved amendments to existing legislation of martial law, including forcible population transfers and holding of elections in territories where martial law has been declared.

This suggests that Russia is unlikely to attempt to capture additional Ukrainian territories – at least, not for now.

Rather, the Kremlin seeks to consolidate its hold on what it already has annexed. This is most likely an attempt to withstand Ukrainian pressure during Kiev’s anticipated offensive until it runs out of steam.

A failure by Ukraine to regain significant ground on the battlefield, in the Kremlin’s logic, might increase the chances of a ceasefire that would further strengthen its territorial control.

Such an outcome might also fracture the West’s united front of support for Ukraine, especially ahead of another winter war and as the US is heading into a fiercely contested presidential election in 2024.

Ukraine’s message to Russia

Ukraine’s best chance of avoiding such an outcome is to make significant gains in its counteroffensive campaign. The drone strikes on Moscow can be seen as preparations for that.

They will provide a boost to morale for the Ukrainian army and people, ahead of what is likely to be a costly and painful military push. They demonstrate that Ukraine is ready to take the fight to the enemy, and that no one is invulnerable to their retribution.

In attacking deep inside Russia, these strikes will also force Russia to keep air defenses close to symbolically and strategically important assets, rather than deploying them closer to the frontline with Ukraine.

The attacks also send a message to the Russian people that the “special military operation” is making them less, not more, secure. Putin has so far presented the war as something that has had little impact on Russian daily lives.

These drone attacks and the coming counteroffensive, with all the destruction and casualties it is sure to bring, will puncture that lie.

David Hastings Dunn is Professor of International Politics in the Department of Political Science and International Studies, University of Birmingham and Stefan Wolff is Professor of International Security, University of Birmingham

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Aem Cyanide case nearly ready for prosecutors

Surachate confident of evidence against accused serial killer

Police are preparing to wrap up their investigation into suspected serial killer Sararat “Aem Cyanide” Rangsiwuthaporn and submit their report to prosecutors next week.

Investigators had found evidence to implicate Ms Sararat in the cyanide poisonings, deputy national police chief Pol Gen Surachate Hakparn said on Friday. They had examined purchase records for more than 700 bottles of cyanide and found that “Aem Cyanide” had purchased one bottle.

A total of 11 deaths took place not long after the deadly chemical was in her hands, Pol Gen Surachate said at the Royal Thai Police Office.

“Now, Aem’s story is completely over because we found that she was the one who ordered the cyanide. Everything is connected,” he said.

Ms Sararat, 36, was arrested on April 25 at the Chaeng Watthana Government Complex in Bangkok. She was four months pregnant at the time. Her arrest followed a complaint filed by the mother and sister of Siriporn “Koy” Khanwong, 32, of Kanchanaburi.

Siriporn collapsed and died beside the Mae Klong River in Ban Pong district of Ratchaburi, where she had gone with Ms Sararat to release fish for merit-making on April 14. Cyanide was found in her body.

The list of her alleged victims has continued to grow. All told, she faces 14 charges of murder and one charge of attempted murder.

Pol Gen Surachate said he believed a serious gambling addiction could have been a factor that pushed Ms Sararat to murder 14 people using cyanide.

An analysis of the 78 million baht that had passed through bank accounts held by the accused suggested she had a bad gambling habit, the deputy chief said on May 19.

On Saturday, the investigation team will start collating all the details in its report. It will then coordinate with the Office of the Attorney-General (OAG) to submit the report into 15 cases against Ms Sararat next week, said Pol Gen Surachate.

After that, investigators will turn their attention to cases against factories and those who purchased cyanide from them. They are also looking into whether officials at the Department of Industrial Works, which regulates the factories, were complicit.

Other charges of violating the Consumer Protection Act are also possible, he added.

“I assure that the investigation report will be concluded next week,” he said. “The investigative report is now almost 100% complete. I will coordinate with the director-general of the OAG to hold a joint meeting and submit the report.”

According to Pol Gen Surachate, Sararat purchased cyanide online two years ago, based on evidence of money transfers for the purchase. Both the buyer and the company that sold the chemical would face charges.

He brushed off a threat by the suspect’s lawyer to file a defamation complaint against him, saying he and his team handled their task in a straightforward manner and never slandered anyone.

The lawyer, Thannicha Aeksuwannawat, made the threat last week after reporting to police to answer charges of assisting her client in destroying or concealing evidence of a crime.

She denied all the charges and said she would file defamation suits against certain police officers and media outlets.

Singapore recalls EGO Honey Dates due to excessive levels of sulphur dioxide

SINGAPORE: The Singapore Food Agency (SFA) has ordered a recall of EGO Honey Dates after detecting sulphur dioxide beyond permissible levels. The allergen, which was not declared on the food packaging, was found at levels “exceeding the maximum limit” stated in Singapore’s Food Regulations, SFA said in a media releaseContinue Reading