NEW YORK – Central Asian countries increased imports from China in March by 55% over the year-earlier month, beating the 35% jump in Chinese shipments to Southeast Asia reported previously.

Former Soviet republics as well as Turkey and Iran all contributed to a near-record gain in Chinese exports to the region, a focus of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative.

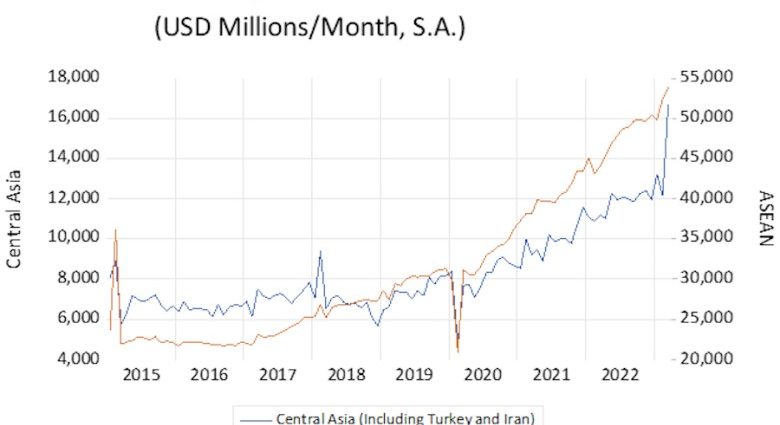

China’s exports to the region have nearly tripled since 2018. The chart below includes Turkey and Iran in the Central Asian total.

Several factors contributed to the export boom, which included every country in the region.

China is investing heavily in energy, mineral resources and rail transport across the Asian continent, including a new rail line between China, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan scheduled to start construction next year.

The rail project, which will link China to European markets, has been planned since 1997 but only won approval in 2022, after Russia backed the venture. Russia’s need for Chinese support in the Ukraine war outweighed longstanding strategic rivalries between the two powers.

“The CKU railway is crucial to China for two interconnected purposes—to advance its geopolitical interests and to secure favorable relations with Central Asian elites for their support over Chinese legitimacy in Xinjiang (East Turkestan),” Niva Yau Tsz Yan wrote in a March 2023 commentary for the Foreign Policy Research Institute.

“Russia’s war in Ukraine has made new trade routes bypassing Russia more profitable, and a new Uzbek government is looking to expand regional and international engagement,” Yan wrote.

Iran’s imports from China had fallen to just US$800 million a month during 2019-2022 from a 2014 peak of $2.8 billion a month. But seasonally-adjusted Chinese shipments to Iran more than doubled to $1.7 billion in March.

Chronically short of cash, Iran depends on trade credits from China, by far its largest trading partner. The March increase evidently reflected more Chinese financing, and came after Iran accepted Chinese mediation in restoring diplomatic relations with its regional arch-rival Saudi Arabia. A reasonable inference is that Iran was being rewarded for good behavior.

China’s exports to Russia continued to rise sharply, along with exports to Turkey, which acts as an intermediary for Chinese trade with Russia. China has avoided direct violation of American sanctions on Russia, but Turkey and former Soviet republics have resold sanctioned goods to Moscow. The sharp increase in China’s exports to Kazakhstan probably reflects this intermediation.

Reuters reported on March 27 that Kazakhstan “would require exporters to file additional documents when sending goods to Russia, following reports that Russian companies have been using local intermediaries to bust Western sanctions… After the West barred sales of thousands of goods to Moscow over its invasion of Ukraine, some Kazakh businesses started purchasing such items and reselling them to Russian firms.”

China’s export prowess isn’t entirely free of tensions, though. In March, Turkey imposed a 40% tariff on imports of Chinese electric vehicles (EV’s), hoping to protect a local manufacturer. The Turkish automaker Togg plans to release its first EV later this year with a sticker price of $50,000.

A comparable Chinese model, for example, BYD’s Song sedan, sells for $27,500 in China—which means that BYD would still undercut Togg’s price despite the 40% surcharge. Meanwhile, BYD has just released its $11,300 Seagull subcompact, which has no competitor in the price range anywhere in the world.

In the kaleidoscope of Central Asian politics, a myriad of local factors explains the jump in China’s influence in the region. But all of them line up like iron filings before a magnet. China’s capacity to provide physical and digital infrastructure as well as affordable consumer goods, and its capacity to finance trade and investment out of its current account surplus, explain its economic power and political influence in the region.

There’s another geopolitical consequence of China’s export prowess in Central and Southeast Asia: China’s exports to the Global South and BRICS countries in March reached a seasonally-adjusted annual rate of $1.6 trillion a year.

That’s nearly four times China’s exports to the United States and more than the combined total of China’s exports to the US, Europe and Japan, which reached a seasonally-adjusted annual rate of $1.38 trillion in March.

That represents a geopolitical point of no return of sorts, the moment when China’s economic dependence on the United States in particular and developed markets in general slipped behind its economic standing in the developing world.

Follow David P Goldman on Twitter at @davidpgoldman