The large waves of foreign capital suddenly racing China’s way are raising a vital question for 2024: is sentiment toward Asia’s biggest economy swinging back toward positivity?

Investors will be and already are debating this very question now that China has racked up a nearly six-fold increase in foreign buying of bonds in November from October – 251 billion yuan (US$33 trillion) of inflows.

But here’s the better question:

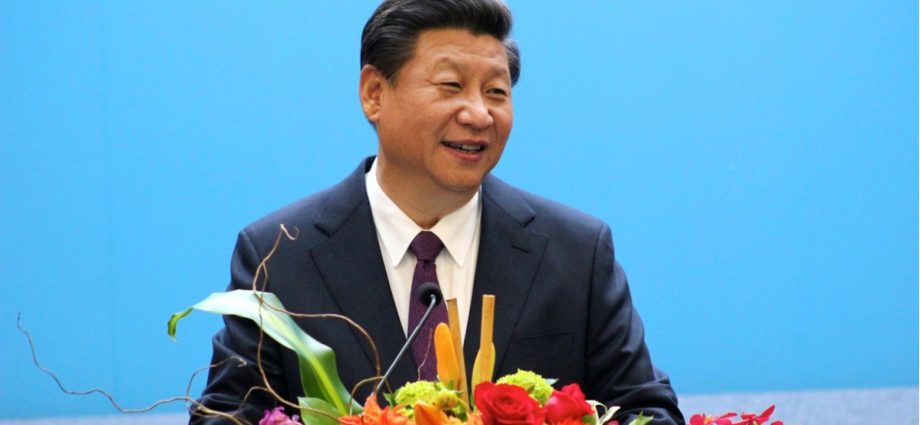

What can Chinese leader Xi Jinping do to lean into the trend and broaden it?

The obvious answer is for the People’s Bank of China to keep doing what it’s done in recent months. Governor Pan Gongsheng’s team has been a study in restraint as other top central banks took decidedly activist approaches to 2023’s economic and financial uncertainties.

Despite the wreckage of Xi’s Covid lockdowns and China’s property crisis this year, the PBOC only cut official rates twice. It prioritized targeted liquidity to money markets to boost growth.

Granted, Chinese borrowing costs are already at record lows. But Pan’s determination to put yuan stability ahead of Japan-like bursts of extreme stimulus – even as deflation stalked the economy – is now paying dividends in the form of big bond inflows.

Of course, Team Xi displayed its own restraint in 2023, foregoing the massive stimulus jolts investors everywhere expecting.

But as 2024 arrives, it is high time for Xi’s government to accelerate moves to build more international and robust capital markets. It is equally important to internalize and heed warnings from Moody’s Investors Service.

On December 5, Moody’s downgraded Beijing’s credit outlook to negative from stable, citing “structurally and persistently lower medium-term economic growth” and a cratering property sector.

The good news, as Moody’s pointed out, is the “economy’s vast size and robust, albeit slowing, potential growth rate, support its high shock-absorption capacity.” The bad news is that headwinds hitting cash-strapped local governments and state-owned enterprises are “posing broad downside risks to China’s fiscal, economic and institutional strength.”

China wasn’t happy. The Finance Ministry acknowledged it was “disappointed” with Moody’s outlook cut. “China’s economy,” the ministry retorted, “is shifting to high-quality development, new drivers of China’s economic growth are taking effect and China has the ability to continue to deepen reforms and respond to risks and challenges.”

As such, Beijing officials called concerns about the country’s growth, fiscal trajectory and economic prospects “unnecessary.”

Yet Xi’s reform team, led by Premier Li Qiang, would be wise to internalize what Moody’s is saying and heed its warnings. The reason is that, fair or not, Moody’s is highlighting the broader conventional wisdom about China’s 2024.

Clearly, the 251 billion yuan jump in foreign bond inflows in November is an important ray of hope. At a minimum, it raises the specter that China can recoup 2022’s record outflows of 616 billion yuan (US$86.3 billion).

“The bond market remains bullish, and market rates will trend lower,” analysts at Guotai Junan Futures write in a note to clients.

Yet sustaining inflows at this pace requires bold policy upgraded to increase transparency and competitiveness.

In recent months, another mainland milestone came into focus: the yuan’s fast-rising share of global payments to the 3.6% mark. Although China still lags behind America’s 47% share by a healthy margin, it would be at Washington’s peril if the US ignored the nearly 2% jump in yuan use in the first 11 months of 2023.

This year, the yuan overtook the euro to become the second-most-used currency in trade, according to data from the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, or SWIFT. As of September, the yuan’s share of SWIFT payments hit 5.8%.

Some of this increase reflects China’s rising economic status; some reflects concerns about the health of the dollar as Washington’s debt tops US$33 trillion. And some reflects the work Xi’s government has done to internationalize the currency since 2016.

That was the year when the PBOC, then under Governor Zhou Xiaochuan, secured a place for the yuan in the International Monetary Fund’s “special drawing-rights” program. The yuan’s inclusion in the IMF’s exclusive club of reserve currencies, joining the dollar, euro, yen and pound, was a pivotal moment for Beijing’s financial ambitions.

Over time, Xi’s reformists took it out for a ride by increasing the channels for foreign investors to tap mainland stock and bond markets. Shanghai stocks were added to the MSCI index, while government bonds were included in the FTSE Russell benchmark among others.

As demand for the yuan surges, Beijing is tolerating a stronger yuan as rarely before. Arguably no policy would jolt Chinese growth faster or more convincingly than a weaker exchange rate. Yet Xi’s Ministry of Finance has avoided engaging in a race to the bottom versus the yen, earning it points in market circles.

Increasing trust among global investors, though, requires a clear and bold commitment to structural reforms. Topping Xi’s to-do list are:

- increasing transparency,

- prodding companies to strengthen governance,

- crafting reliable surveillance mechanisms,

- developing an independent credit rating system and

- building a robust market infrastructure.

The more Xi develops dynamic capital markets, the more foreign investors will send waves of capital China’s way. And the more willing mainland households will be to invest in stocks and bonds over real estate.

Another top priority is devising a broader network of social safety nets to encourage households to spend more and save less. This step alone would help recalibrate growth engines from exports and excess investment to domestic demand.

These reforms would go a long way to reducing the frequency of the boom/bust cycles that all too many investors associate with China and to change the subject from the regulatory crackdowns of the last three-plus years that started with Alibaba Group’s Jack Ma.

Here, Xi’s government did itself no favors this month with controversial new gaming restrictions. Although Beijing has throttled back a bit, investors fear a crackdown on the world’s largest mobile arena.

“Although we think the short-term selloff is likely to continue in the coming days, given investor frustration and negative readthrough to internet and general China equity regulation risk, we believe the share price reaction to the exposure draft is overdone,” says JPMorgan Chase & Co. analyst Alex Yao. “We expect a negative but insignificant impact on Tencent and NetEase’s gaming monetization.”

All this shines a bright spotlight on the big China reform question: Does Xi’s government need more stimulus to create space to shake up China’s economic model?

“For the past year and more, investors have been waiting for a different type of pivot in China: when the government finally gets serious about growth again,” says economist Andrew Batson at Gavekal Research.

Still, recent signals from Beijing “showed an attempt to find a new balance between growth concerns and broader objectives that top leader Xi Jinping has laid down, such as technological self-sufficiency and national security.”

Barton adds that a “recalibration would be welcome to investors.” He notes that “arguably the major issue afflicting economic policy in 2023 has been the government’s conviction that it could have its cake and eat it too. The hope was that a long-term drive to build high-tech industries and bolster the country against external threats could double as a short-term stabilization plan.”

“But that strategy suffers from a time inconsistency problem,” Batson says. “The favored growth sectors of the future, even big ones like electric vehicles, are simply too small today to offset the damage from the rapid decline in the property sector.

Batson adds that “the government has shown it’s happy to throw vast sums of money at ‘good’ sectors through industrial policy, but real economic stabilization requires broad-based support of aggregate demand – allowing the ‘bad’ sectors to get money, too. On this front, the language from [recent deliberations in Beijing] showed more willingness to deploy the traditional levers of fiscal and monetary policy.”

Even more important, though, is creating conditions necessary to ensure today’s capital inflows lead to tomorrow’s prosperity.