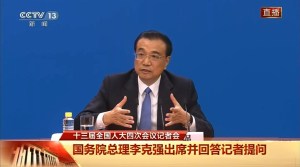

TOKYO – As China scrambles to stimulate growth, it’s comforting to see Chinese Premier Li Keqiang internalizing – apparently – the works of Milton Friedman.

How so? By recalling the Nobel Prize-winning economist’s edict that a crisis is a terrible thing to waste.

This week, Li called on local officials in six key provinces to take bold action to put a floor under China’s economy. These six regions — which drive 40% of gross domestic product — are precisely where Beijing should be looking as growth flatlines. Output and consumption are cratering amid Covid lockdowns and sliding property values.

Li wants local governments to increase debt issuance programs “reasonably,” to act “according to law,” while new construction projects should prioritize “sound” fundamentals.

But it is not just Friedman whom Li is channelling.

After the conclusion of a national leadership conclave, Li travelled to Shenzhen this week to “present a flower basket to the statue of Comrade Deng Xiaoping at Lianhuashan Park,” Xinhua reported.

Likely with Deng, the great reformer, in mind, Li said, “China must continue the reform and opening-up process.” He added with a poetical twist, “The waters of the Yangtze will not flow backwards.”

Fine words, but to dive into the detail: Li thinks it’s time China got serious about building a stable, trusted and globally attractive bond market. And what better time than now as the debt-issuance machinery booms back to life?

The white elephant hunt

At a recent State Council meeting, Li stressed that the financial system must have a clear and credible framework that ensures the orderly issuance of government bonds and municipal debt to ensure projects are transparent and productive.

“Fund management should be strengthened to forestall debt risks and prevent the idleness of funds,” Li explains. “The construction of new government buildings in violation of regulations must be strictly prohibited and no vanity projects will be tolerated.”

This no-white-elephant-projects mindset is vital on three levels.

One: Attracting the foreign capital flows needed to fuel growth and internationalize Chinese markets. Two: Removing fuel from the very reckless borrowing behavior Beijing tried to discourage with the deleveraging campaigns of recent years. Three: Putting China on a more sustainable long-term trajectory.

Deeper capital markets are critical to building a consumption-based economy. They’re central to giving smaller private firms — including tech startups — access to financing to expand and disrupt a top-down growth model. They’re key to creating dynamic social safety nets to absorb a fast-aging population.

Clearly, the pressure is on to jumpstart GDP. The topic seemed to dominate the party’s annual conclave at the beach resort of Beidaihe in Hebei Province.

Low-growth vs. open markets

News that China grew just 0.4% in the April-June quarter year-on-year has President Xi Jinping’s government scrambling to roll out fresh fiscal stimulus. Xi is a mere few months away from securing a precedent-breaking third term as Communist Party leader.

Qi Wang, CEO of MegaTrust Investment, finds great significance in the fact that Li made zero mention of the 5.5% growth target.

“In fact,” he notes, “you can hardly find any references to this in any official talks or documents lately. Does this mean China is abandoning the apparently unachievable target? I think so.”

Nomura Holdings is now forecasting 2.8% growth this year, while Goldman Sachs expects 3%. Last month, the International Monetary Fund lowered its China forecast to 3.3% from an earlier 4.4%.

“China’s post-Omicron rebound has fizzled out and the prospects for near-term growth are poor,” says economist Julian Evans-Pritchard at Capital Economics. “Virus outbreaks are happening with increasing frequency.”

Beijing’s latest budget is expected to empower local authorities to issue at least $220 billion of extra debt this year for infrastructure purposes. The six provinces that Li is relying on — Guangdong, Henan, Jiangsu, Shandong, Sichuan and Zhejiang — already account for roughly 60% of China’s total foreign trade and foreign investment.

Having them lead the stimulus charge makes eminent sense. The Politburo has long turned to economically vibrant regions to spearhead efforts to boost national growth. The key, though, is using this latest Covid-crisis response as an opportunity to improve China’s bond market infrastructure. That means increasing transparency, building a more credible domestic credit rating agency system and moving toward full yuan convertibility.

China is working on it, of course.

On June 30, the People’s Bank of China gave overseas investors access to onshore exchange-based bond markets in Shanghai and Shenzhen. PBOC Governor Yi Gang’s team argues this opening move, coupled with coming reforms to mainland fixed-income markets, will “further facilitate investing by foreign institutional investors in the Chinese bond market and unify the cross-border management of funds.”

Even before that opening step, Beijing allowed more than 1,000 foreign institutional investors to deal in the centralized interbank bond market. The China Securities Regulatory Commission and Hong Kong’s Securities and Futures Commission are working on additional opening steps, including add exchange-traded funds to programs connecting China-region markets.

But the more foreign influence China allows into its $20.6 trillion debt market, the less Xi’s party can get away with the financial opacity that pervades today’s market.

Li, Friedman, Deng and Carville

As Li riffs off Friedman and Deng, there’s an argument that China also needs a James Carville moment.

The reference here is to the early 1990s, when President Bill Clinton’s administration found itself constrained by the bond market. Any sign the White House might expand the budget deficit sent US Treasury yields skyrocketing.

At the time, Carville, a senior Clinton advisor, famously remarked: “I used to think that if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the president or the pope or as a .400 baseball hitter. But now I would like to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.”

In recent years, particularly since 2015, Xi’s government faced several episodes of stock market chaos.

Each time, including earlier this year, Beijing was able to pull bourses back from the brink. In 2015, for example, Beijing reduced reserve requirements and loosened leverage protocols. It halted all initial public offerings and stopped trading in thousands of listed companies. It allowed average Chinese to use apartments as collateral so they could buy shares. It urged households to buy stocks out of misplaced patriotism.

But the bond market is a very different animal, as Carville observed. When you lose the trust of bond traders, you lose control over interest rates and the currency.

The intimidating gang to which Carville referred is the so-called “bond vigilantes” who rebel against policies on the part of governments or central banks they consider unwise or dangerous. Their protests can be powerful and destabilizing. As they drive up yields and boycott debt auctions, governments can suffer big surges in borrowing costs.

Many top officials in Beijing have been reluctant to accord this kind of power to private investors – especially foreign ones. But this would be a necessary evil in order to build a more credible and efficient debt market.

Transparency, transparency, transparency

One of the reasons default dramas like the one surrounding China Evergrande Group tend to surprise traders is the lack of market visibility. The underdeveloped nature of China’s credit-rating industry and other yardsticks means that yield spreads are less of a reliable early-warning system for the nation’s markets.

China Inc.’s black-box nature tends to warp credit spreads, yield dynamics and secondary-trading liquidity. The worry is that if China does hit a wall, it could be quite a surprise to world markets.

More efficient debt markets also might enable Beijing to gain greater traction with stimulus moves.

“This strategy is hardly a surprise,” says economist Andrew Batson at Gavekal Research. “Infrastructure has been a regular countercyclical tool for China since the response to the global financial crisis of 2008.”

Batson notes that “with most other growth drivers sputtering, the reliance on infrastructure this time around is even greater. That doesn’t bode well for the business cycle. The efficacy of infrastructure spending is often overrated, and on its own has never been enough to turn around the cycle. Unless and until the government can stabilize the property market, growth could continue to grind lower despite the public-works largesse.”

There are two Japan-like challenges China appears to be facing. One is a liquidity trap caused by banks finding little demand for tidal waves of credit the PBOC churned into markets. The second is that conventional fiscal stimulus is losing potency at the very worst moment for China’s slowing economy.

Headwinds are intensifying from all angles – from Federal Reserve tightening in Washington to Xi’s endless “zero Covid” lockdowns at home. Property sector distress isn’t helping, says Charlene Chu, a former Fitch Ratings analyst known for her warnings about Chinese debt risks.

“We’ve got a property sector that is almost dead and used to employ huge numbers of people and a lot of downstream industries,” says Chu, now a senior analyst at Autonomous Research. “All of that is getting impacted by this property slowdown, and that’s why I think we’re still early in the game here.”

Should China face a debt reckoning, Li knows it would be easier to address if it had resilient and trusted capital markets. The implications are critical. Carville, remember, is known, too, for his observation that “it’s the economy, stupid.”

Follow this writer on Twitter @WilliamPesek