While Joe Biden is trying to calm concerns about recession and Christine Lagarde is scaring markets with quantitative easing (QE), the central banks of South Korea and Japan are pleasing investors in their own way.

Starting with the “Land of the Rising Sun,” despite Japan’s 2.84 trillion yen (US$19.7 billion) intervention in the foreign-exchange market in the last week of September, the yen is trading against the dollar above the 148 level. Excessively bearish sentiment is built on the strong dollar and dovish commentary from Bank of Japan (BOJ) governor Haruhiko Kuroda.

Despite the fact that a weak yen is harmful to the economy as it makes business planning difficult for companies by inflating the cost of raw-material imports, no drastic move is expected from the regulator. The BOJ could continue the cycle of interventions to support the local currency; however, the effect will be short-lived.

It is worth mentioning that with the current level of debt, the BOJ cannot afford to change the course of its monetary policy. Otherwise, the country could face a credit event. According to Fitch Ratings, higher bond yields will make it harder for Japan to stabilize or reduce its public-debt-to-GDP ratio.

AMRO research, on the other hand, suggests that Japan’s sovereign credit rating could fall one to three notches in the coming decade if the government does not implement a credible fiscal consolidation plan. Currently, Japan’s credit rating has been reaffirmed by Fitch Ratings as “A” with a “stable” outlook.

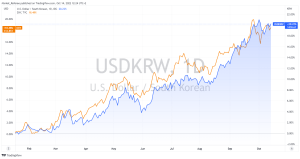

As for South Korea, the local currency is back to 13-year lows. The recent increase of the benchmark interest rate by 50 basis points wasn’t enough to gain market confidence. Things could change if the regulator actually resumes the purchase of corporate bonds and commercial paper worth up to 1.6 trillion won (US$1.12 billion).

But can tight monetary policy and QE co-exist? Not only is it permissible, but it is practiced. As an example, despite the rate increase, the European Central Bank’s printing machine is in no hurry to stop. To be more precise, there are plans to begin quantitative tightening (QT) but no action whatsoever. The Bank of England was also forced to resume its bond-buying program to save pension funds and the pound sterling.

The problem is that one mechanism contradicts the other. As the European regulator notes, the program supports economic growth and inflation. Thus, despite higher interest rates, inflation pressures keep building. Importantly, growing debt-servicing costs can cause debt ratios and debt dynamics to deteriorate and rollover risk to rise.