In the homestretch of 2023, China is calming fears for the year ahead that it might engage in a race to the bottom on exchange rates.

In recent days, China’s biggest state-owned banks bought the yuan in unison to support the currency. By swapping yuan for dollars in onshore markets and selling those dollars in spot markets, major banks are reassuring traders worried Beijing might chase the falling Japanese yen lower.

There are a few possible explanations for why China is putting a floor under the yuan. One is to reduce default risks among property developers servicing offshore debt. Another is to avoid fresh trade tensions with Washington. Beijing also wants to stanch the capital outflows now making global headlines.

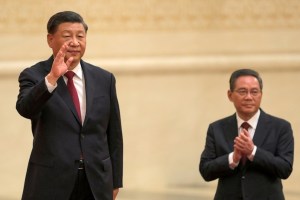

What’s interesting, though, is that Chinese leader Xi Jinping is tolerating a firmer yuan at a moment when Asia’s biggest economy could really use an export boost. Overseas shipments fell 6.4% in October year on year following a 6.2% drop in September.

Yet Xi’s long-term commitment to internationalizing the yuan is taking precedence over short-term economic growth priorities — and that’s likely a good thing.

Since 2016, when China won inclusion into the International Monetary Fund’s top-five currencies club, Xi has made increasing the yuan’s role in trade and finance a major policy priority.

This objective paints China’s capital outflows dynamic in a new light. In other words, not all outflows are “bad” given that a large share at the moment appears to reflect China Inc leveraging overseas growth.

In the first 10 months of the year, China’s non-financial outbound direct investment (ODI) increased 17.3% year on year to 736.2 billion yuan (US$104 billion).

“The allure of new global markets and evolving business models are driving Chinese enterprises to venture abroad and expand their presence on the global stage,” notes economist Yi Wu, an author of the China Briefing newsletter published by Dezan Shira & Associates.

There are valid reasons why China’s take of foreign direct investment flows is facing headwinds. One is default concerns confronting County Garden Holdings and other giant property developers.

Photo: CNBC Screengrab / Zhang Peng / LightRocket / Getty Images

Another is disappointing data on manufacturing and retail sales. Xi’s team also has been slower to ramp up stimulus than in the past, fanning complacency concerns.

Yet an argument can be made that Xi’s real goal is staying focused on longer-term retooling, not short-term economic sugar highs.

“China only takes meaningful actions when there is a real crisis. The government and the market may have different opinions on whether China has an economic crisis,” says As Qi Wang, CEO of MegaTrust Investment. “It turns out the market over-worried, and China may be right not to over-stimulate.”

China, he adds, “doesn’t seem to be in a crisis mode,” at least “until recently” when the government finally realized it faces a “confidence crisis” as the economy slides back into deflation.

In recent weeks, this manifested itself in Beijing’s “national team” buying shares in top banks and loading up on exchange-traded funds to boost investor confidence. Xi’s recent visit to San Francisco, where he made nice with US President Joe Biden, marked the start of a financial charm offensive.

But machinations in Beijing smack more of longer-term objectives than panic in Communist Party circles. This goes, too, for China deflation risks, which burst back into global headlines.

Last month, mainland consumer prices fell a greater-than-expected 0.2% year on year. While not precipitous, the trend adds to “evidence of renewed economic weakness,” Capital Economics wrote in a note to clients.

Still, economist Robert Carnell at ING Bank calls it a “pernicious” turn of events for Xi’s party. “What China has right now,” he explains, “is a low rate of underlying inflation, which reflects the fact that domestic demand is fairly weak.”

Data show that Chinese suppliers of goods face intensifying headwinds, too. China’s producer price index, which measures goods prices at the factory gate, dropped 2.6% in October year on year.

The trend “reflects uncertainty around the solidity of China’s recovery,” says HSBC economist Erin Xin. It “will likely keep policymakers on guard to keep support coming through.”

And yet many observers are surprised the People’s Bank of China isn’t acting more forcefully to attack deflationary forces, lest “Japanification” speculation might intensify. The yuan exchange rate may be the missing link.

At a moment of ebbing global confidence in China’s economy, Xi and the PBOC are working to display some at home. The rationale appears to be that a stable exchange rate communicates self-assuredness on the part of Chinese institutions.

The PBOC is encouraging lenders to cap the volume of new loans in early 2024. Governor Pan Gongsheng’s team also is prodding banks to shift some lending programs forward to stabilize China’s credit cycle. Again, few hints of panic.

Here, the ODI-is-a-good-thing argument also comes into play. Increased outward direct investment is a natural sign of economic maturity whereby domestic firms expand operations to foreign countries.

As Japan and South Korea demonstrated, it’s natural to tap overseas growth in case domestic markets become saturated.

In the first 10 months of 2023, Chinese ODI increased 11% from a year earlier. This strategy both reduces concerns about China’s balance of payments and hints at a longer-term payoff to Beijing keeping its cool.

Looking at Japan’s example, deflationary currents require a major recalculation in economic planning. Part of it is the PBOC knowing what it can and can’t control.

The capital outflows China is experiencing are as much a product of rising US bond yields as concerns about Xi’s economic strategies.

It remains unclear whether the US Federal Reserve will tighten rates further in the weeks ahead. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell’s team remains noncommittal.

This uncertainty is keeping Sino-US rate differentials at levels that favor the dollar. As money seeks higher returns, Chinese FDI fell nearly $12 billion in July-September year on year, the first quarterly drop since the State Administration of Foreign Exchange began reporting the data in 1998.

All this makes the yuan’s recent rise to four-month highs all the more noteworthy. At a minimum, it buttresses the argument that Beijing is propping up the yuan in defiance of where traders might want to push exchange rates.

This helps explain why as exports fall for a sixth straight month, imports are rising in ways that could support neighboring economies. Imports rose 3% from a year earlier to $218.3 billion. With exports dropping to $274.8 billion, Beijing’s trade surplus is now $56.5 billion, a 17-month low.

The lessons from Japan suggest that deflation tends to portend a strong currency down the road. Yet in Tokyo’s case, the emphasis has been on defying the laws of economic gravity and engineering a weak exchange rate.

As 2024 approaches, Japan is being reminded of the limits of this strategy. Since the late 1990’s, government after government clung to a weak exchange rate strategy to support the export-geared giants towering over Japan’s economy.

Yet the last decade of Bank of Japan hyper-easing merely exacerbated Tokyo’s all-liquidity-no-reform problem. It produced record corporate profits but failed to incentivize companies to boost wages, invest big in innovation, increase productivity or take risks on promising new industries.

A weak yen is the cornerstone of 25 years of modern capitalism’s most generous corporate welfare, one that continues to hold Japan back. Why should CEOs bother restructuring, recalibrating or reimagining industries when the BOJ prints free money decade after decade?

Xi’s team seems determined to avoid this outcome. Of course, Xi’s work to increase the yuan’s global footprint is far from done.

“The internationalization of the RMB is an ongoing process, with a promising future for China ahead,” says economist Elvira Mami at the Overseas Development Institute think tank. “Nevertheless due to the tight capital controls in China which prevent capital outflow, despite its growing use, the RMB is not likely to replace the US dollar in the nearest future.”

Of course, discussions of China’s troubles can tend toward hyperbole.

“We do see some indications that supply chain shifts are underway globally and that FDI decisions are changing as well,” says Jeremy Zook, director of Asia-Pacific at Fitch Ratings. “But our view is that China will likely remain the dominant player in global supply chains for a long time and such shifts will only be gradual.”

A key prerequisite is restoring trust in China as a destination for capital. Since late 2020, when Xi launched a crusade against tech founders — starting with Alibaba Group’s Jack Ma — China has too often been in global headlines for all the wrong reasons. This has had Wall Street analysts debating whether China was becoming “uninvestable.”

Since March, newish Premier Li Qiang has worked to flip the script. Li’s team stepped up outreach efforts to reassure overseas chieftains that China is once again open for business.

The efforts come as international business lobbies urge Beijing to level playing fields, reduce local protectionism, make the regulatory environment less erratic and tamp down on national-security-related crackdowns.

In San Francisco last week, Xi received something of a hero’s welcome from Western CEOs keen to re-engage with China Inc. Attendees included Apple’s Tim Cook, Tesla’s Elon Musk and Blackstone’s Steve Schwarzman, among others.

Equally important, Xi and Li are making their most assertive push to date to fix China’s property crisis. The vital sector faces a nearly $450 billion shortfall in cash needed to regain its footing and to complete millions of unfinished apartments weighing on local economies.

Li’s reform team is cobbling together a list of 50 builders that will receive financial support. Among the distressed developers Beijing is targeting are Country Garden and Sino-Ocean Group. If coupled with bold regulatory reforms, investors have reason to hope China will avoid Japan’s lost decades.

The structural reform piece is vital. Any steps to increase transparency, allow full yuan convertibility, create a robust credit rating matrix, increase the size and freedom of the private sector, curb the role of state-owned enterprises and build social safety nets to encourage greater consumption would cheer global funds and improve China’s FDI trends.

Efforts by Xi and Li to communicate that China is addressing these cracks and others are clearly falling short, witnessed in the huge capital flight unsettling world markets.

Yet even here it’s best to remember that not all the capital leaving reflects investors giving up on China. A growing share of outflows reflects China Inc going global in ways to be expected from any fast-rising economic superpower.

The same goes with letting the yuan rise, a sign that China’s leaders and policymakers aren’t as worried about the trajectory of the economy as many would suspect.

Follow William Pesek on X, formerly Twitter, at @WilliamPesek