Foreign businesses have been pulling money out of China at a faster rate than they have been putting it in, official data shows.

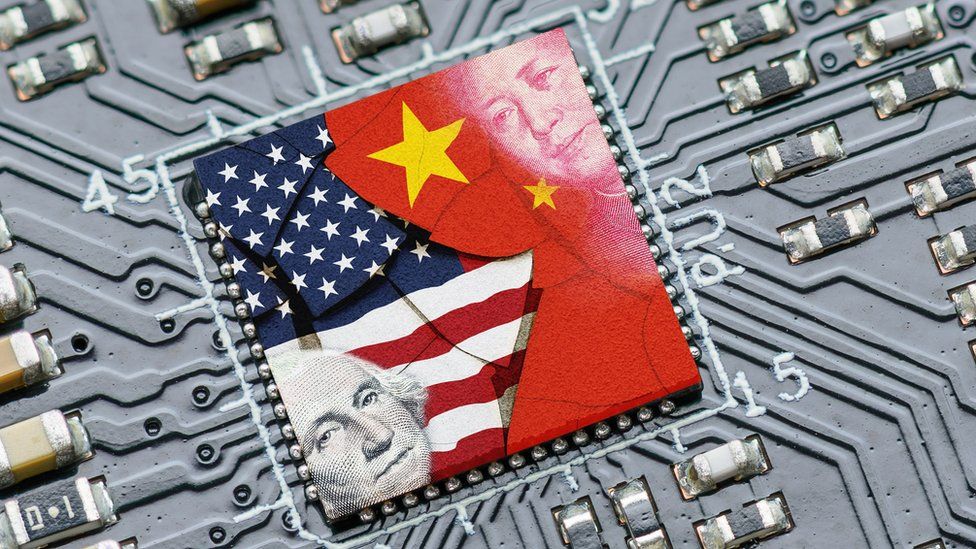

The country’s slowing economy, low interest rates and a geopolitical tussle with the US have sparked doubt about its economic potential.

All eyes will be on a crucial meeting between Chinese leader Xi Jinping and US President Joe Biden this week.

But businesses appear to be already erring on the side of caution.

“Anxieties around geopolitical risk, domestic policy uncertainty and slower growth are pushing companies to think about alternative markets,” says Nick Marro from the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU).

China recorded a deficit of $11.8bn (£9.6bn) in foreign investment in the three months to the end of September – the first time since records began in 1998.

This suggests that foreign companies are not reinvesting their profits in China, rather they are moving the money out of the country.

China needs to make ‘corrections’

“China is currently facing slower growth and needs to make some corrections,” says a spokesperson for the Swiss industrial machinery manufacturer Oerlikon, which pulled 250m francs ($277m; £227m) from China last year.

“In 2022, we were one of the first companies to transparently communicate that we expect the economic slowdown in China to impact our business,” the spokesperson adds. “Consequently, we began early to implement actions and measures to mitigate these effects.”

China remains a key market for the firm. It has close to 2,000 employees across the country, which accounts for more than a third of its sales.

Oerlikon noted that the Chinese economy was still expected to post growth of around 5% in the next few years, “which is among the highest in the world.”

Since the onset of the pandemic, businesses like Oerlikon have contended with the challenges of operating in what is the world’s biggest market.

China had implemented one of the world’s strictest pandemic lockdowns through its “zero-Covid” policy.

This caused disruptions to the supply chains of many companies, such as technology giant Apple, which makes most of its iPhones in China. The firm has since diversified its supply chain by moving some production to India.

Mr Marro believes more companies have heeded calls for diversification this year, as tensions between China and the US rose with fresh export restrictions on raw materials and technology needed to make advanced chips.

“We aren’t seeing many companies pulling out of China. Many of the big multinational firms have been in the market for decades, and they’re not willing to give up market share that they’ve spent 20, 30 or 40 years cultivating. But in terms of new investment, in particular, we are seeing a reassessment.”

Low interest rates

Businesses are also considering the impact of interest rates. China bucked the trend as many countries around the world raised rates sharply last year.

Many major central banks, including the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank, have been hiking interest rates to tackle inflation. The higher cost of borrowing, which promises higher returns, also attracts foreign capital.

Meanwhile policymakers in China have cut the cost of borrowing to support its economy and struggling property industry. The yuan has depreciated by more than 5% against the dollar and euro this year.

Rather than reinvesting China earnings back in the country, business are spending the money, the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China says.

It adds: “Those with excess cash and earnings in China have been increasingly transferring these funds overseas, where they will earn a higher investment return compared to investments in China.”

Some firms had withdrawn earnings from China as “part of their long-term cycles” of taking profits “once their projects reach a specific scale and profitability”, Michael Hart, president of the American Chamber of Commerce in China, observed.

“The withdrawal of profits does not necessarily indicate that companies are unhappy with China, but rather that their investments here have matured.”

Mr Hart says it’s “encouraging because it means companies are able to integrate their China operations into their global operations.”

Canada-based aerospace electronics company Firan Technology Group invested up to C$10m ($7.2m; £5.9m) in China over the last decade, and withdrew C$2.2m from the country last year and in the first quarter of 2023.

“We are not exiting China at all. We are investing and growing our business there and taking out any excess cash to invest elsewhere in the world,” says the firm’s president and chief executive Brad Bourne.

“We had surplus cash in China and bringing it back to help fund our recent US acquisitions was just prudent cash management, and it meant that our borrowing was reduced,” he adds.

Uncertainty ahead

Analysts say there is much uncertainty about what lies ahead – both in terms of interest rates and China-US ties.

China’s central bank could move to lower interest rates further this year to support its economy, says Dan Wang, the chief economist of Hang Seng Bank China.

Lowering interest rates could put more pressure on the already weakened yuan. “There is very limited room for monetary easing right now because of the pressure of currency depreciation,” she says.

“If economic sentiment improves next month, it’s safe to say that China will lower interest rates. But if sentiment doesn’t improve, the central bank will have a very difficult decision to make.”

Businesses are cautiously optimistic about the upcoming meeting between Presidents Xi and Biden, says the EIU’s Mr Marro.

“Direct meetings between the two presidents tend to exert a stabilising force on bilateral ties. We have also seen a flurry of US-China diplomatic engagement over the past couple of months, which has contributed to this feeling that both sides are aiming to put a floor under the relationship,” he says.

“That said, it doesn’t take much for things to fall apart again. Until companies and investors feel like they can navigate with more certainty, this drag on foreign investment into China will continue.”