Seeing “China Evergrande Group” trending on global search engines is the last thing Xi Jinping needs as 2023 goes awry for Asia’s biggest economy.

News that exports plunged 14.5% in July year on year was the latest blow to China’s hopes of growing its targeted 5% this year. It’s the biggest drop since February 2020, when Covid-19 was sledgehammering trade and production worldwide.

Yet the default drama at Country Garden Holdings is a reminder that the call for help is coming from inside China’s economy.

This week, Country Garden was trending in cyberspace as it faced liquidity troubles akin to those of the humbled China Evergrande in 2021.

The whiff of trouble that tantalized markets in recent weeks proved true amid reports noteholders failed to receive coupon payments due on August 7.

That has global investors worried about an Evergrande-like domino effect. “If Country Garden, the biggest privately owned developer in China, goes down, that could trigger a crisis in confidence for the property sector,” says Edward Moya, senior market analyst for Oanda.

Analyst Sandra Chow at advisory firm CreditSights notes that “with China’s total home sales in the first half of 2023 down year-on-year, falling home prices month-on-month across the past few months and faltering economic growth, another developer default – and an extremely large one, at that – is perhaps the last thing the Chinese authorities need right now.”

The risk is slamming investor sentiment toward China. And it spotlights the urgent need for Chinese leader Xi and Premier Li Qiang to repair the shaky property sector and accelerate state-owned enterprise (SOE) reform.

A more vibrant and resilient property market is crucial to China’s economic recovery in the short run and reducing the frequency of boom-bust cycles in the longer run. The sector, if running smoothly, can generate as much as one-third of China’s gross domestic product.

Earlier this month, Li pledged to “adjust and optimize” Beijing’s approach to building a healthier, more stable property market. Li has urged major cities to devise measures to stabilize markets in their own jurisdictions.

That followed a pledge by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) to provide developers with 12 additional months to repay their outstanding loans due this year.

This week’s default chatter raised the stakes. On August 3, Moody’s Investors Service slashed Country Garden’s credit rating to B1, putting it in the “high risk” category.

“This downgrade reflects our expectation that Country Garden’s credit metrics and liquidity buffer will weaken due to its declining contracted sales, still-constrained funding access and sizable maturing debt over the next 12 to 18 months,” says Moody’s analyst Kaven Tsang.

Country Garden’s stock has cratered over the last week after the company’s warning of an unaudited net loss for the first six months of 2023. Clearly, Country Garden has been grappling with liquidity chaos for some time.

As the company noted in a July 31 exchange filing, it “will actively consider taking various countermeasures to ensure the security of cash flow. Meanwhile, it will actively seek guidance and support from the government and regulatory authorities.”

A day later, Country Garden reportedly canceled an attempt to raise US$300 million by selling new shares.

As analysts at Nomura wrote in a note, “recent signals from top policymakers… suggest Beijing is getting increasingly worried about growth and have clearly recognized the need to bolster the faltering property sector. They are starting a new round of property easing and may introduce some stimulus to redevelop old districts of large cities.”

More important, though, is for Xi and Li to tackle the underlying cracks in the financial system. The sector’s troubles are structural, not cyclical.

Thanks partly to slowing urbanization and an aging and shrinking population, demand for new housing is on the wane. When economists worry about a Japan-like “lost decade” in China, the unfolding property crisis is Exhibit A.

The more that already massive oversupply increases, the more difficult it’s becoming for Beijing’s stimulus to flow through to construction activity.

And the more the property sector acts like a giant weight around the economy’s ankles, the more China’s financial woes look like Japan’s bad-loan crisis.

This dynamic is a clear and present danger to China’s ability to surpass the US in GDP terms, a changing of the economic guard many thought might happen as soon as the early 2030s. Yet so is the slow pace of SOE reform as China’s economic model shows growing signs of trouble.

Xi and Li clearly understand the urgency. In recent months, Xi’s Communist Party set out to help boost the valuations of SOE stocks, which represent a huge share of China’s overall market.

According to Goldman Sachs Group, SOEs in sectors from banking to steel to ports account for half the Chinese stock market universe. Yet Xi’s talk of creating a “valuation system with Chinese characteristics” is a work in progress, at best.

The SOE conundrum is a microcosm of Xi’s challenge to balance increasing the role of market forces and boosting investment in listed state companies, while also pulling more international capital China’s way.

In his second term in power, from 2018 to 2023, Xi more often than not tightened his grip on the economy at the expense of private sector development and dynamism.

The most drastic example was a tech sector crackdown that began in late 2020. It started with Alibaba Group founder Jack Ma and quickly spread across the internet platform space.

Since then, global money managers have grown increasingly more cautious about investing in Chinese assets. This, along with a steady flow of disappointing economic data, is undermining Chinese stocks, which are among the worst-performing anywhere this year.

That has given Xi and Li all the more reason to ensure that the practices of China’s largest state-owned giants come into better alignment with global investors’ interests and expectations.

China needs a huge increase in global investment to realize its vision for a 5G-driven technological revolution. Monetary stimulus can’t get China Inc there any more than Bank of Japan stimulus can revive Japan’s animal spirits.

Given the fallout from Covid-19 and crackdowns of recent years, China’s biggest tech companies are no longer cash rich or self-supporting. And the transition from SOE-driven to private sector-led growth has become increasingly muddled.

“If SOEs are able to pick and integrate the right targets, control risk effectively and promote innovation, outcomes should be credit-positive for the firms involved and beneficial for China’s growth,” says analyst Wang Ying at Fitch Ratings.

The global environment hardly helps, as evidenced by recent declines in export activity. US efforts to contain China’s rise – whether one calls it “decoupling” or de-risking” – is an intensifying headwind.

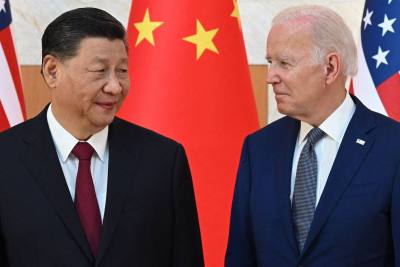

On August 9, US President Joe Biden detailed new plans to curb American investments in Chinese companies involved in perceived as sensitive technologies such as quantum computing and artificial intelligence.

Though nominally aimed at preventing US capital and expertise from flowing into mainland technologies that could facilitate Beijing’s military modernization, the limits are sure to have an added chilling effect on market sentiment.

Lingering pandemic fallout hardly helps. Adam Posen, president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, a Washington-based think tank, argues that China is suffering “economic long Covid” that could mean its condition is even weaker than global markets realize.

In a recent article in Foreign Affairs, Posen said that “China’s body economic has not regained its vitality and remains sluggish even now that the acute phase – three years of exceedingly strict and costly zero-Covid lockdown measures – has ended.

He warns that the “condition is systemic, and the only reliable cure – credibly assuring ordinary Chinese people and companies that there are limits on the government’s intrusion into economic life – can’t be delivered.”

Xi is, of course, trying. The campaign, which recently fueled a jump of over 50% in some SOE stocks, is accompanied by a slogan of buying into a “valuation system with Chinese characteristics.”

Last month, Chinese Vice Premier Zhang Guoqing said the government is redoubling efforts to deepen and hasten SOE reform.

Zhang, a member of the Political Bureau of the Communist Party of China Central Committee, said the aim is to boost core competitiveness and prod SOEs to innovate, achieve greater self-reliance and raise their science and technology games.

More recently, Liu Shijin, a former vice minister and research Fellow of the Development Research Center, said government agencies must begin viewing entrepreneurs not as “exploiters” but as growth drivers.

But pulling off a transition toward private sector-driven growth would be much easier to pull off if China’s underlying financial system was more stable. The biggest risks start with the property sector.

“The problems of China’s property developers are only getting more severe,” says economist Rosealea Yao at Gavekal Dragonomics.

“The sales downturn is likely to throw many more private-sector developers into financial distress — a risk underscored by Country Garden’s recent missed bond payments. Unless sales can be stabilized, developers will be trapped in a downward spiral.”

Yao cites three reasons why a continued downturn in sales could push many private sector property developers into financial distress.

First, private developers have been mostly shut out of capital markets and thus unable to roll over maturing bonds since late 2021, when China Evergrande fueled investor concerns that other highly leveraged private sector developers would also be unable to repay their debts.

“Private sector developer issuance in the onshore bond market is now minimal, and has collapsed in the offshore market as well,” Yao says. “Companies with state ownership, by contrast, still mostly retain the faith of onshore bonds with bondholders demonstrating that they are not entirely risk-free.

“The combination of both weak revenues and lack of refinancing ability has led many firms to default or negotiate repayment extensions since the start of 2022, and the number of defaults and extensions remains elevated this year.”

Two, cash liquidity positions of private sector developers are deteriorating. According to the annual reports of 86 non-state-owned developers, she notes, short-term liabilities exceeded cash on hand by 725 billion yuan ($100 billion) in 2022, compared to a shortfall of 171 billion yuan ($23 billion) in 2021.

“This,” Yao says, “suggests that the firms may have insufficient liquidity to repay their maturing debts – though Country Garden boasted more cash on hand than its short-term liabilities at the end of 2022, suggesting this measure could understate the problem, as developer reserves may be shrinking rapidly this year.”

Third, many private-sector developers are not just illiquid – they are getting closer to insolvency. That is mostly due to rising impairment charges as the companies are forced to recognize that assets on their balance sheets have declined in value, often under pressure from auditors.

“Such charges deplete the asset side of companies’ balance sheets, pushing them closer to a situation in which the value of their liabilities could exceed the value of their assets — similar to the more traditional path to insolvency through negative net profits reducing equity,” she adds.

Again, Xi and Li clearly know what needs to be done to put China on more solid economic and financial ground. They just need to accelerate badly needed reform moves – before more indebted property developers like Country Garden hit investor confidence in the country’s prospects and direction.

Follow William Pesek on Twitter at @WilliamPesek