This research appeared earlier this week in the Asia Times ‘ International Risk-Reward Monitor, a regular examination of market forces.

Given our current position of information about the new government’s intentions, we foresee a steadily deteriorating socioeconomic environment in 2025 with continual high interest rates, higher than expected inflation, and weaker than expected earnings.

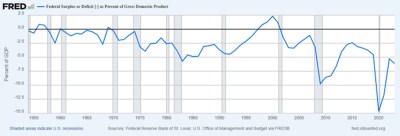

The Biden Administration bequeathed Donald Trump the largest-ever federal deficit ( at 6.1 %  , of GDP ) in an economic expansion.  , The president-elect wants to renew , his 2018 corporate tax cut at an estimated cost of$ 400 billion per year,  , and , eliminate taxes on Social Security income at a cost of about$ 150 billion per year.  , That would raise the federal deficit, now at$ 1.7 trillion, by about a quarter, minus possible revenues from additional tariffs ( which now bring in about$ 80 billion a year in revenue ), and whatever cost savings , his team can obtain from spending reductions.

What didn’t go on forever didn’t, according to Okun’s Rules, and the United States doesn’t continue to run up the federal deficit continuously. But it has a price to pay to continue doing so for the near future. America doesn’t encounter a” Liz Truss time” , , as Swiss Re economist , Jerome Jean Haegeli , told the Wall Street Journal , November 21, referring to , the blowup of the UK tie business in October 2022 after the short-tenured prime minister proposed deep tax cuts.  , For the time being, the US can fund the Treasury’s saving need with , local resources. However, that comes at a high price, and it’s possible that financial pressure may become stronger in 2025.

Unlike the aftereffects of the 2008 World Financial Crisis, when foreign central banks financed the boom in Treasury loans, US regional economic institutions , absorbed the bulk of post-Covid Treasury financing, with some help from international personal investors and US homes. The presence of financial institutions in Treasury funding is more clearly visible graphically in terms of levels.

Lenders can continue to get Treasuries, but only if interest rates remain high. According to McKinsey, return on equity for large parts of the finance sector would be lower than the institutions ‘ individual cost of capital without the rise in interest rates of the previous two years. The supply on medium-term Treasuries is approximately equivalent to the bank’s loans from the central bank, which means that the deficit cannot be funded by the legendary printing press. Deposits, while, cost much less than borrowed money, and the Biden Administration’s massive governmental increase of 2019-2020 unleashed a flood of payments into the banking system. Payments rose much faster than institutions ‘ loans and leases, and were channeled into Treasuries.

That began a period in motion. Federal subsidies caused the gap to balloon, but a sizable percentage of those subsidies were reinvested back into the Treasury securities that provided the deficit. The grants unleashed prices, and the Federal Reserve , raised interest rates, making Treasuries appealing for businesses.  , Higher interest rates , doubled the cost of servicing the federal debt, to$ 1 trillion last year from$ 500 million in 2020.

In short, the rising of Treasuries on banks balance sheets, the higher price setting, the higher deficit expected to doubled interest payments, and higher inflation are all facets of the same problem.

What could go bad?

For one thing, a year ago, the surge in payments that made it possible for banks to purchase Treasuries with inexpensive customer money stopped. Lenders will have to make a higher yield than they already receive for immediately money from the Federal Reserve in order to continue funding the deficit. The secured over funding rate is currently higher than the supply of five-year Treasuries.

Businesses can use inexpensive reserves to finance buying of Treasury securities, but no expensive borrowings from the central bank. As we see in the chart above,  , the year-on-year shift in business businesses assets of US Treasury and Agency stocks tracks the year-on-year shift in payments.

Lenders will only be able to continue funding the Treasury gap once the spread between the central bank’s cost of funds and the produce on Treasury securities has dried up. One chance, of course, is that the main institution could provide cheaper revenue to the banks. That would in effect allow the printing press to fund the Treasury deficit, which is a badly inflationary move. Fed head Jerome Powell didn’t do this.

Another possibility is that medium-term Treasury yields need to climb. Rising long-term curiosity rates, though, may reduce if not eradicate economic growth.

Furthermore, US households may stop consuming and purchase a lot more government securities.  , American families save only 4.4 % of their disposable income, or about$ 1 trillion a year. If homeowners doubled that to$ 2 trillion a month, they could fund the gap by themselves. However, a rapid decline in use may lead to a recession, lower taxes revenues, and a bigger deficit.

Accidents are often feasible – for example, a big problem in the multi-trillion industry for short-term funding of government securities. As the Federal Reserve shrank its portfolio holdings of Treasuries, the illiquidity of the Treasury market ( as measured by the bid-asked spreads of off-the-run Treasuries ) worsened.

However, it’s unlikely that a liquidity seize-up would cause any long-term harm. Central banks have a way to react to these kinds of situations; they simply purchase whatever is available until the market drops.

The consequence of the expansion of US debt, high inflation, high Treasury rates and high debt service costs is likely to be gradual – a headwind, not a cyclone.  , This will hit US consumers the hardest.

US consumers borrowed money from credit markets to maintain their level of consumption after the Biden subsidies expired in response to high ( and significantly higher than expected ) inflation. Credit card debt increased significantly, while the interest rate on revolving credit increased from 14 % to 22 %. Revolving credit’s total interest payments increased from$ 100 billion to$ 250 billion last year.

The tax cuts that Trump’s team has  , discussed don’t have supply-side effects. Extending the old corporate tax cut doesn’t change incentives to invest, and removing taxation of Social Security benefits won’t bring more 70-year-old into the workforce.  , Tariffs cannot help but increase prices, both for consumers and for production inputs. Higher tariffs on imported capital goods will likely lead to a lower investment because the US currently imports more capital goods domestically than it produces.