Among the wackiest things to come from Donald Trump’s mouth recently is the former US president trying to take credit for China’s US$7 trillion stock reckoning.

“I mean, look, the stock market almost crashed when it was announced that I won the Iowa primary in a record,” Trump told Fox News on February 11. “And then when I won New Hampshire, the stock market went down like crazy.”

In reality, China’s spectacular stock rout has been playing out since 2021, well after Joe Biden moved into the White House. But there is one investor crowd taking notice of the growing odds Asia might soon be grappling with a Trump 2.0 presidency: currency traders.

Trump’s threats to impose tariffs exceeding 60% on Chinese goods has the cost of hedging the yuan soaring to the highest levels since 2017.

In China, “the most frequently asked questions among local investors include implications for China should Donald Trump become the next US president,” says Goldman Sachs economist Maggie Wei after a series of recent meetings with mainland mutual funds, private equity funds and asset managers.

Even today, well before Trump might have a chance to shake up global trade anew, “the outlook for trade flows going forward is likely one of moderation,” says Rubeela Farooqi, economist at High Frequency Economics. The downshift is thanks to “expectations of slower demand and growth going forward, both domestically and abroad.”

The specter of a supersized trade war is the last thing the global economy needs as 2024 unfolds. Any added headwinds from the West would compound the domestic troubles that have knocked Chinese stocks sharply lower, namely a deepening property crisis, weak retail sales, sputtering manufacturing activity and deflationary forces.

The threat of significantly higher taxes on Chinese-made goods destined for the US could slam business and household confidence. Executives might be even less inclined to add new jobs at a moment when youth unemployment is at record highs.

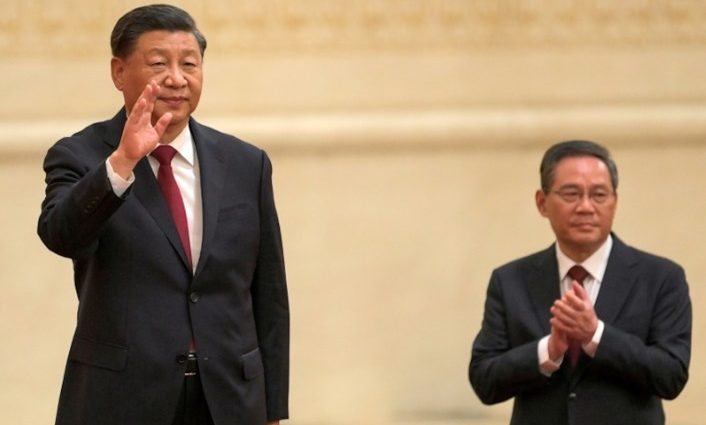

Trade war worries also might make China Inc less willing to fatten paychecks. This could imperil President Xi Jinping’s hopes of recalibrating economic engines toward a consumer demand-led growth model.

It also could lead to a big spike in exchange rate volatility and put downward pressure on the yuan. That’s precisely what Xi and Premier Li Qiang don’t want in 2024. For one, it could increase default risks of property developers with offshore debt. For another, it could set back Xi’s success to date in deleveraging the financial system.

Then there’s the upcoming US election. The one thing on which President Joe Biden’s Democrats and Republicans loyal to Donald Trump agree on is being tough on China. And a weaker yuan falling ahead of the November 5 contest could provoke Washington in unpredictable ways.

In the meantime, the mere threat of a bigger trade war could spook investors currently piling into US stocks. If Trump were to add another 60% tariff on top of those that he imposed during his 2017-2021 presidency, American consumers would bear the brunt through costlier goods.

Trump’s initial trade war neither catalyzed a US manufacturing boom nor narrowed the US trade deficit with China. Meanwhile, the US government had to throw billions of dollars of federal aid to US farmers as China scrapped purchases of American agricultural goods in retaliation.

A big spike in US tariffs would necessarily be inflationary, complicating the US Federal Reserve’s hopes of cutting interest rates. Prolonging the period of high US bond yields would undermine corporate America while also reducing household disposable spending.

The inflationary impact of a Trump 2.0 presidency could shake up the economic trajectory of nations everywhere, not least in export-oriented Asia. An analysis by Bloomberg Economics reckons that a 60% tax on all Chinese imports would effectively shrink a vital $575 billion trade relationship to a trickle.

All this leaves Xi’s Communist Party with decidedly mixed feelings about whether China would fare better under another four years of Biden or a second Trump term.

On the surface, at least, Biden is endeavoring to restore ties with Xi’s party, a pivot on full display last November when Xi visited San Francisco for the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit, a grouping dedicated to trade promotion.

Biden, though, has so far refused to lift the Trump-era tariffs that so enraged Xi’s economic team. The Biden administration also has gone at China’s soft targets with surgical precision, including limiting its access to cutting-edge technology like high-end semiconductors and the gamut of chipmaking equipment.

The last two years also saw the US devise a screening program to curb investments in China’s efforts to raise its game in quantum computing and artificial intelligence. Though Biden has taken the rhetorical tone down a notch, his policies have arguably exacted greater damage than Trump’s.

This includes investing hundreds of billions of dollars in domestic tech capacity that the Trump administration neglected. The US building new economic muscle at home worries Xi more than 1980s-style policies around which China can generally easily navigate. Here, think of Trump’s failed effort to kill giant Chinese telecom gear maker Huawei.

Looked at through this prism, there’s an argument that China might prefer Trump redux. As Zhu Junwei of Grandview Institution notes, there’s a reason the Beijing think tank’s research suggests 60% of Chinese prefer Trump because of how his unruly presidency might further dent America’s global standing.

Either way, Xi’s party is bracing for an US election cycle sure to see Democrats and Republicans trying to one-up each other at China’s expense.

Increased data security measures are sure to emerge as the year unfolds. The icy reception Shou Zi Chew, CEO of ByteDance-owned TikTok, received on Capitol Hill recently dramatized the race to curb services and transactions across industries.

China’s electric vehicles (EVs) market could face its own onslaught of data security speed bumps from either a Biden or Trump administration.

In a speech in late January, Biden’s National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan said there are “competitive structural dynamics” in the US-China relationship. But, he claimed, this competition “doesn’t have to lead to conflict, confrontation or a new Cold War.”

It already seems too late for that. But as November 5 approaches, currency traders are becoming increasingly antsy, as seen in recent spiking volatility. The gap between nine-month implied volatility on the offshore yuan and measures of six-month volatility is the highest in nearly seven years.

As that electoral contest approaches, strategists at Deutsche Bank expect the US dollar will stay mainly within 2023 ranges even if the US Federal Reserve begins cutting interest rates, as many investors expect. “The market is likely to start adding to a dollar safe-haven premium through the year as election risks build,” Deutsche Bank argues in a note.

There’s an argument, too, that the dollar might be doomed if Trump gets another shot at naming a Treasury secretary. In 1971, then-US president Richard Nixon’s Treasury chief famously said that “the dollar is our currency, but it’s your problem.” This seems even truer now than in 1971 and the sentiment could be supersized during a Trump 2.0 presidency, if his first term was any guide.

While running for president in May 2016, Trump even hinted at defaulting on US debt. Trump told CNBC “I love debt. I love playing with it.” When asked what he might do if the budget deficit grew too fast, he said: “I would borrow, knowing that if the economy crashed, you could make a deal. And if the economy was good, it was good. So, therefore, you can’t lose.”

In April 2020, the Washington Post detailed how Trump officials, looking to punish China, mulled canceling debt held by Beijing. However, Treasury officials succeeded in talking Trump out of a stunt that likely would have made the 2008 Lehman Brothers crisis seem like a hiccup.

But who knows what tricks Trump may have up his sleeve in a second term? The risk is hardly a non-negligible worry for Japan, China and other top Asian central banks sitting on more than $3 trillion of US Treasury securities.

The US entered 2024 with its national debt topping $34 trillion and Moody’s Investors Service warning it might yank away America’s only remaining top rating.

That came three months after Fitch Ratings downgraded the US to AA+ as Republicans and Democrats wrestled over funding the government and 12 years after a Standard & Poor’s downgrade amid partisan bickering over the debt ceiling.

More recently, Moody’s warned that “the greatest near-term danger to the dollar’s position stems from the risk of confidence-sapping policy mistakes by the US authorities themselves, like a US default on its debt for example. Weakening institutions and a political pivot to protectionism threaten the dollar’s global role.”

Moody’s adds that “although we expect that politicians will eventually agree to raise or suspend the debt limit and avoid a default on government debt, greater polarization in the domestic political environment over the last decade has weakened both the predictability and effectiveness of US policymaking. Sanctions further inhibiting the free flow of the dollar in global trade and finance could encourage greater diversification.”

Team Biden has raised concerns of its own over a “weaponized” dollar as Washington squares off with Russia over Ukraine. Those allegations emerged after the Biden administration, as part of sanctions, moved to freeze hundreds of billions of dollars of Moscow’s foreign reserves.

Yet at least one thing is clear: Asia’s markets will find themselves in harm’s way as Trump and Biden try to prove on the campaign trail who is tougher on China. But as the rival candidates flex and joust, there is much more at stake than the US presidency.

Follow William Pesek on X, formerly Twitter, at @WilliamPesek