China’s economic aspirations have evolved rapidly. What has remained constant for centuries is a determination to return to the domestic wealth and international power that most Chinese view as the only acceptable norm for a civilization that long led the global economy.

Under Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin (1978– 2003), the leadership’s model of how to achieve that evolved rapidly in the direction of market-oriented reform and international opening to trade and investment, along with political and administrative institutionalization and meritocracy.

Under Hu Jintao (2003–2013), reform, opening, and institutionalization as thus understood largely stagnated; that administration’s achievements focused on elimination of some unfair treatment of farmers, spreading the economic miracle to China’s interior, and surviving the 2008 global financial crisis.

Hu’s legacy included these achievements, but also worsened problems of coordinating parts of the central government, dissonance between the central and local governments and a spectacular increase in the visible scale of corruption.

China’s changing view of the Western model

Until the mid-2000s, China looked up to Western economies and Western polities. That absolutely did not mean that the Chinese intended to copy them in detail, but they saw them as models of how both mature economies and mature polities work.

They took most World Bank advice. They imported Hong Kong officials wholesale in the belief that Hong Kong’s market-friendly structure provided a primary economic model for China. At the turn of the century, the Central Party School was working on three models for democratization, including one modeled on Japan and one on Taiwan.

At a RAND Corporation conference in November 2001, during a debate about Taiwan, the political leader of a Central Party School delegation surprised the Americans by declaring, “We hate everything [then-president] Lee Teng-hui is doing in cross-Straits relations, but we admire the way he has taken Taiwan politics to a new level.”

The Carter Center and the International Republican Institute were advising on village elections. There was even high-level discussion of whether someday Taiwan’s Guomindang Party might be allowed to compete and win in China’s Fujian Province.

Two things changed that reverence for supposedly more mature Western models. The global financial crisis of 2008 shocked and damaged China and convinced officials there that greater government control of the economy was essential to prevent crises and recover from them.

The emergence of Donald Trump and Boris Johnson reduced to absurdity, in their view, any argument that Western democracy would ensure governance in the interest of the people.

This puts us in a situation analogous to the 1920s and 1930s. On one side was visionary socialism charging forward with attractive social arguments, but implemented by institutions that severely damaged human dignity. On the other side was laissez-faire democratic capitalism that produced advanced technology but also catastrophic business cycles, wanton ecological destruction exemplified by the Dust Bowl, unsafe food and a combination of tycoons and heartlessly exploited workers that was morally indefensible.

Subsequently, the totalitarian socialist side proved unable to adapt and self-destructed. The democratic capitalist side learned to moderate its business cycles through novel fiscal and monetary policies and it borrowed socialist and socialist-like ideas such as social security, government medical insurance, strong unions, support for farmers, food safety regulation and suffrage for women and Native Americans. This ability to learn and adapt ensured survival and victory.

Western democratic capitalism is again in trouble. Pew Research polls show US popular support for democracy declining rapidly. Viktor Orbán of Hungary and other illiberals are more sustainable than Trump. Whether our system retains its historic ability to adapt is an open question.

Unlike the late Soviet Union, China has been very adaptable, but one must ask whether Beijing’s current leaders are destroying that adaptability.

China’s new economic model

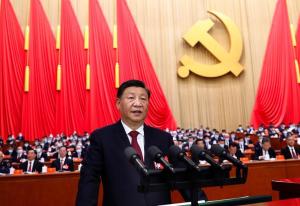

Under Xi Jinping, China seeks to create a new system with extremely centralized executive leadership of the government and state enterprise leadership of the economy while retaining the full benefits of market competition.

It wants to strengthen the state enterprises while retaining the benefits of a private sector that provides 90% of urban employment, 100% of net job creation, over 50% of exports, and, according to Vice Premier Liu He, more than 70% of all innovation.

Likewise, it wants to retain the advantages of foreign direct investment while preventing foreign companies from attaining a leadership role in any Chinese sector and while achieving Chinese global dominance in every aspect of modern manufacturing.

In this new system, state enterprises will control the commanding heights of the economy. The government will support the private sector, but every company will have a party secretary with ultimate decision power over strategic business decisions and every company will eventually have at least a small share of government ownership.

Foreign investment will be encouraged, but foreign companies will never be allowed to dominate any important sector. The education system will be remodeled and shortened to rigorously support industrial needs.

The overarching theme of Xi’s new model is “common prosperity,” and the core promise of common prosperity is a fairer system without the divisive income and wealth inequality that currently plagues both China and the United States.

This is an inspiring wish list – as socialist critiques and promises a century ago were inspiring. Actual policies are accomplishing much that Western democracy currently seems incapable of implementing, such as exceptionally rapid progress on green energy.

But it is also a wish to have one’s cake and eat it too. Foreign companies and countries will reject a system where they are lured in for their technology but excluded from the kind of market access that China demands from the West.

Xi’s support for the private sector is sincere – but no matter how many times he tells the big Beijing banks to lend more to private companies, they still will never get their money back if they obey. Bank executives are punished, sometimes severely, when the money doesn’t come back. Subsidized state enterprises eat up the private ones. Private sector investment and growth have plunged.

The extensive political controls on business will be either costly or ineffective. Xi’s administration has forgotten one of the central lessons of socialism’s history: Political leaders believe state ownership will give them control of the economy, but the big companies inexorably end up owning the politicians.

The German education and apprenticeship model, which Xi seems to be copying, is seductive – but it has largely confined the German economy to refining early twentieth-century technologies like the automobile while the United States dominates the modern service economy.

China’s industrial policies look like 1970s Japan, which had some very expensive successes and even more expensive failures. While Xi has waged a sincere war against corruption, hierarchical single-party states grow corruption the way a wet log grows mushrooms.

The Beijing administration is imposing this new system, or important parts of it, in the context of the weakening of the core drivers that have driven China’s exceptional growth, along with emerging drags on growth. More on this below.

Above all, achieving the fairness promised by the “common prosperity” slogan will ultimately require a substantial property tax, a highly progressive income tax, termination of the controls on migration to the cities, greatly liberalized rural land rights and a shift in the balance of taxing power between the center and the localities.

So far, Xi has used campaign-style tools – fire top executives, press big companies and rich people to contribute to charities, weaken the political power of companies – but 11 years of high-level conversation about the needed property tax have failed to implement even an experimental version.

Ultimately, Xi and Biden appear equally impotent to alter their countries’ egregious maldistribution of wealth.

China’s long-term economic prospects

Ironically, just as Chinese triumphalism is fading in China, a mirror of it continues in the United States. Many commentators, particularly those associated with the US defense establishment, project superior Chinese economic growth indefinitely into the future and infer that China will soon overwhelm US power.

I suppose I bear some responsibility as the first one to compile impressive Chinese statistics and predict that China would become a superpower, back in my then-controversial 1993 book The Rise of China: How Economic Reform Is Creating a New Superpower. But three decades have elapsed and the gee-whiz industry is becoming obsolete.

That industry assumes that superior past Chinese growth implies superior future Chinese growth. Even though forecast numbers are adjusted downward, they typically are not based on clear economic analysis of what will drive growth.

A surprising amount of higher level “Chinese” manufacturing is actually foreign companies’ production based in China, and the technological progress of many Chinese companies has relied on collaboration with foreign companies that are becoming disillusioned with unfair Chinese practices.

Historically, the United States overestimates its competitors and underestimates itself. Throughout the Cold War, Americans (intelligence agencies, economists, media opinion makers and informed public opinion) egregiously overestimated the Soviet economy. In the 1970s and 1980s, we grossly exaggerated Japan’s prospects. Most recently, we have grossly overestimated Russian military capabilities.

One way the prowess of Japan and China has been exaggerated is by focusing on manufacturing prowess and ignoring the service economy, which is larger and more important than manufacturing even in China. US dominance of services likely will persist.

The core drivers of China’s “miracle” growth have been heavy infrastructure, property development and urbanization. During this decade, those drivers will be largely exhausted.

Property already shows signs of plateauing or tipping over. The property and infrastructure booms leave mountains of debt that must be serviced. This means that by 2030 China’s growth potential should be similar to that of the United States.

The heavy political controls that Xi is imposing will, if they persist and are strongly implemented, slow that growth. Officials’ innovative entrepreneurship at all levels has been a crucial source of growth; under Xi’s tight controls, that entrepreneurship has largely died.

In China’s graying society, the number of working-age people is declining and the welfare burden of caring for the aged is increasing. The Japanese experience shows what an extraordinary burden a graying society can be. China’s graying problem is worse. Increasingly, China is mimicking Japan’s failed industrial policies.

In addition, the party is using party committees and government ownership stakes to intrude into the decision-making of every business. A banking system that has become much more centralized and hierarchical cannot adequately service the private sector economy that provides most economic growth, all net new jobs and most innovation.

Vice Premier Liu believes that innovation will replace the old drivers, but the political controls, the emphasis on state enterprise control of the commanding heights of the economy and the collapse of private sector funding and investment will hinder innovation.

For decades of the reform era, GDP grew fast and government revenue grew at twice that rate. This created the illusion in Beijing and abroad that China had unlimited resources. Now GDP grows more slowly and government revenue growth has to converge with GDP.

The severe belt-tightening of the Belt and Road Initiative and the debt problems resulting from its early extravagance are indicators of incipient, painful sobriety.

Xi having gotten his third term, the controversies over zero-Covid, Russia, decapitation of the big platform companies, political controls on the economy, private sector malaise, severe political repression and extreme decoupling of Chinese elites from global society will be sand in the gears of the economy for five years, possibly followed by a historic succession struggle.

In all these aspects non-economists tend to repeat the errors of the past, exaggerating the power of a competitor and undervaluing their own country. A slower-growing China will remain a huge market and a superpower, but it will not remain today’s dominant driver of growth in developing economies and dominant magnet for developed countries’ corporations.

While China’s GDP may still become as large as America’s, that may not imply overwhelming geopolitical clout. In purchasing power terms, China is already larger. In nominal terms, it may well reach America’s by 2030 or earlier. But its per capita income will still be a fraction of America’s and its technological level may seriously lag.

Harvard Professor Lawrence Summers vividly captured the comparison problem when he recently pointed out that, if the United States absorbed Mexico, its GDP would increase but its international power would not necessarily increase. Inside China are many Mexicos.

Likewise, University of California Professor Bradford DeLong has characterized China as sixty million people living at Spanish levels, three hundred million living at Polish levels, and one billion living at Peruvian levels.

Given its loss of powerful drivers and its demographic problems, China’s potential growth after 2030 is probably similar to that of the United States. Xi’s over-centralization, Japan-style industrial policy, kneecapping of the private sector, and political controls may further reduce China’s potential growth.

Therefore, if the United States keeps growing at recent rates, the curve of Chinese GDP might rise to bounce off America’s and then be left behind.

That outcome would depend on efficient US economic management, at best an uncertain prospect. The reality of Sino-American economic competition is that we are currently in a historic race between Xi Jinping and Trump-Biden to see which country can degrade its economic management faster through protectionism, failure to deal effectively with great social changes and dominance of politics over economics.

Presently, Xi is winning that downward race, but no outcome is inevitable.

Geopolitical responses

These are great historical tides. On the historical record, governing elites are very slow to recognize alterations in historical tides. Changed policies tend to occur only when the inertia of ingrained ideas and institutionalized doctrines hits a brick wall.

The assumptions that China’s rise is inexorable, that Xi’s policies are forever, and that the Sino-America relationship is a zero-sum game are already so ingrained in US officialdom and US academia that they are not likely to change soon in line with altered reality.

The brick wall is not currently visible. Let us hope that it will be economic rather than military.

William H Overholt is a senior research fellow at Harvard’s Kennedy School. The author of multiple books about China, he has held RAND’s Distinguished Chair of Asia Pacific Policy and served as president of Fung Global Institute.

This article was first published by The International Economy. Asia Times is republishing it with kind permission.