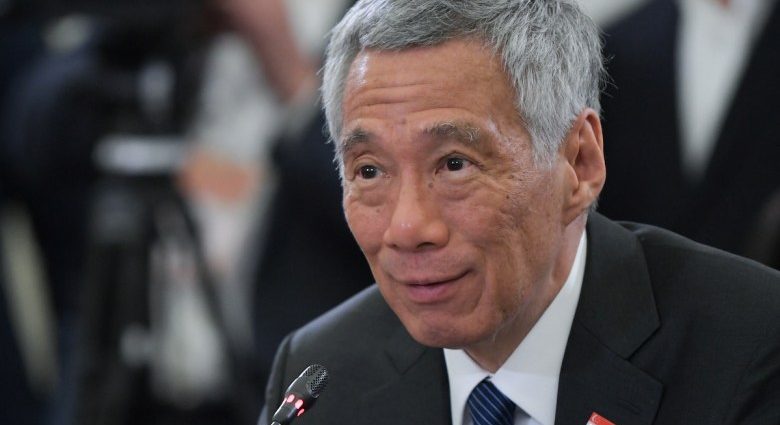

MANILA – “Are you sure you (Filipinos) want to get into a fight where you will be the battleground?”, Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong cautioned at a recent forum in the city-state when asked about rising tensions in the South China Sea.

The leader’s comments came shortly after yet another incident that risked tilting toward violence between Chinese and Philippine coast guard forces.

Manila accused Beijing of conducting “dangerous maneuvers” during its latest resupply mission to the hotly disputed Second Thomas Shoal, a feature which precariously hosts a detachment of Filipino soldiers atop a grounded vessel. Beijing has consistently claimed Manila is the provocateur in recent incidents around the shoal.

In the event, a Chinese Coast Guard vessel fired a water cannon at a Philippine counterpart after Beijing said it “entered the waters adjacent to [Second Thomas Shoal] Reef in China’s [Spratly] Islands without the permission of the Chinese government.”

China also warned the Philippines against refurbishing its de facto naval base in the area, the largely dilapidated BRP Sierra Madre vessel, lest it risk armed confrontation.

For its part, Manila has maintained that since the disputed feature is just a low-tide elevation within its continental shelf, as per a 2016 arbitral tribunal ruling under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the Second Thomas Shoal is not even a territory to be claimed by Beijing.

Western powers, Japan and traditionally neutral nations like India have publicly expressed support for the Philippines amid multiple encounters and near-collisions with Chinese maritime forces in recent months. But most Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) members have remained largely silent on the issue.

“The South China Sea is important, but it is not the only thing at stake,” Singapore’s leader Lee said while expressing his hope that none of the region’s rival claimants “truly want to push it to the brink.”

Malaysia, Vietnam and Indonesia also have rival sea claims with China, but none are pushing back as hard as the Philippines.

Lee’s comments, however, didn’t go down well with many Filipinos who lament the lack of support, if not outright abandonment, from its ASEAN brethren amid its intensifying maritime tussle with the Asian superpower.

Philippine exceptionalism

Home to Asia’s first anti-colonial revolution, the Philippines sees itself as a key member of the Global South. In fact, its voting record at the United Nations has largely tracked with fellow post-colonial nations including among ASEAN members.

At the same time, Manila has aligned with more Western democratic nations during many key UN votes, most notably on the creation of the State of Israel, the recent Ukraine conflict and the current Israel-Hamas war.

Throughout the Cold War period, the Philippines also kept a healthy distance from its more communist-friendly counterparts, most notably Indonesia and India, during the 1955 Bandung Conference.

Although the Philippines is one of the founding members of ASEAN, originally devised as an anti-communist bloc, it has had relatively testy relations with neighbors over the interceding decades. This largely stems from Manila’s geographic and cultural distance from the rest of Southeast Asia.

Geographically, Manila is far closer to Taipei than all ASEAN capitals. Manila is just as close to Guam, Tokyo and Seoul as it is to key Southeast Asian capitals such as Jakarta and Singapore.

This has had major geopolitical implications, namely making Manila historically central to determining the broader order in the Western Pacific and Northeast Asia.

As a former Spanish and American colony, the Philippines’ cultural distance from the rest of ASEAN is just as pronounced. A Catholic-majority nation with a long history of liberal democratic politics, the Philippines has arguably more in common with Latin American nations than some of its immediate neighbors.

And as America’s oldest ally in Asia, the Philippines has been a key pivot point of Washington’s grand strategy in the region. Already enjoying a Status of Visiting Forces Agreement with Australia, the Philippines is also the only Southeast Asian nation to have openly backed the Australia-UK-US (AUKUS) defense pact.

It’s also the only regional state pursuing a Visiting Forces Agreement-style deal with Japan.

The Philippines’ distinct geopolitical alignment is not only a reflection of its unique strategic culture but also an upshot of its growing frustration with ASEAN.

For more than three decades, Manila has incessantly pushed for greater regional diplomatic intervention to protect the interests of smaller claimant states in the South China Sea.

During the negotiation of the UNCLOS in the 1970s, the Ferdinand Marcos Sr administration mobilized regional states in order to collectively lobby for the rights and interests of smaller maritime nations in the UNCLOS negotiations.

Shortly after the bloody Sino-Vietnamese skirmish over Johnson South Reef in the late 1980s, Manila started pushing for a regional Code of Conduct (COC) in the South China Sea.

Thanks to incessant diplomatic efforts by multiple Filipino governments, most notably under the Fidel Ramos administration, ASEAN and China finalized a transitional Declaration on the Conduct of Parties (DOC) in the South China Sea in 2002 as a prelude to a legally binding COC.

Two decades later, however, ASEAN has yet to finalize even a final draft of the agreement, with China constantly dragging its feet and sending mixed signals during the protracted negotiations.

Deafening ASEAN silence

With most ASEAN nations deeply dependent on China’s markets and economic largesse, the COC negotiations have been largely pro forma rather than substantive. To the Philippines’ chagrin, some ASEAN neighbors, most notably Cambodia, widely seen as a China satellite, seem uninterested in even discussing the disputes.

In 2012, ASEAN faced a major diplomatic crisis, when Hun Sen, as the regional body’s rotational chairman, tried to block even the mere mention of the disputes just months after Manila lost control over Scarborough Shoal to China. In response, then-Philippine president Benigno Aquino warned, “The ASEAN route is not the only route for us.”

When the Philippines filed an international arbitration case against China at The Hague, no ASEAN nation expressed public support. Once it was clear that the unprecedented legal case was about to bear fruit, Hun Sen lambasted the Philippines by complaining: “It is very unjust for Cambodia, using Cambodia to counter China…this is not about laws, it is totally about politics.”

Nor did ASEAN as an organization even mention, never mind support, the arbitral tribunal award at The Hague, which rejected the bulk of China’s claims to the sea in favor of the Philippines.

The only exception was Vietnam, which informally supported the Philippines’ arbitration case and, once the final ruling was published, broadly agreed with the precedent and its legal implications for its claims in the South China Sea. Vietnam has since weighed whether to file a parallel case against China over their sea disputes.

In fairness, Singapore, which is not a claimant in the South China Sea, has historically stood for a rules-based order in the region. Ahead of the 2016 arbitral tribunal ruling, Lee also emphasized the importance of UNCLOS as a foundation for managing maritime disputes in the region.

Singaporean leaders, most notably the late Lee Kuan Yew, have also constantly emphasized the importance of America providing a military and economic counterbalance to China in the region.

Although not a US treaty ally, Singapore also has a robust defense relationship with America, including the Memorandum of Understanding in 1990, the Strategic Framework Agreement in 2005 and the 2019 Protocol of Amendment to the 1990 MOU, which granted the Pentagon significant access to the city-state’s naval facilities.

From 2019 to 2021 alone, the United States authorized the permanent export of over US$26.3 billion in defense equipment to Singapore. Significantly, the city-state is the only Southeast Asian nation to gain access to US-made F-35 fighter jets.

Against this backdrop, the Singaporean leader’s recent statements on the South China Sea disputes were met with a mixture of perplexity and criticism in the Philippines, where a vast majority favor a tougher stance against China in tandem with allied nations.

Philippine Foreign Secretary Enrique Manalo has made it clear in the past that the maritime disputes are “not the sum” of bilateral relations with China. Nevertheless, Manila is determined to draw the line in the South China Sea to protect its core interests after six years of fruitless flirtation with Beijing under the Rodrigo Duterte presidency.

And with the rest of ASEAN largely silent on the Philippines’ rising struggle teetering toward confrontation, there is a growing perception that Manila should just rely more on its traditional Western allies rather than fellow ASEAN members, many of which seem more keen to please Beijing rather than uphold regional solidarity.

Follow Richard Javad Heydarian on X, formerly Twitter, at @Richeydarian