The 35% decline in the yen and 25% decline in the euro relative to the dollar, and the US dollar index up by 25% since 2017, are being rationalized as a response to the US Federal Reserve’s raising interest rates to battle inflation. Analysts remind us that such policy is similar to the one Paul Volcker pursued in the 1980s to put an end to inflation.

Not so.

Volcker’s own take is not the only reminder of what is gravely mistaken in both the Fed’s policies and those of all central banks now, as well as the above analyses, but it also shows what would be the lasting, stable solution – not being discussed now.

In his 1992 work Changing Fortunes, Volcker said that between 1980 and 1982, the higher interest rates “attracted more and more foreign funds to help finance our deficits and investments.”

“The adverse repercussions of this policy mix on international markets became obvious – except to members of the administration who interpreted it as a vote of confidence in US policy. [But] the high interest rates and a strongly rising dollar made it harder to deal with the debt crisis [and] the competitive position of our industry; and markets began to be seriously undermined.”

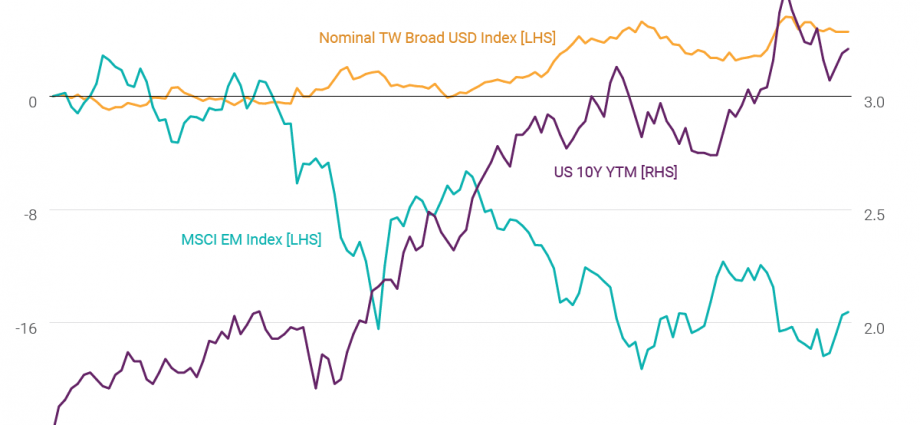

This is similar to the scenario unfolding now before our eyes, as the wildly gyrating exchange rates noted above show. Dollar-indebted countries’ currencies such as India’s and Chile depreciated this year, and Sri Lanka defaulted on its overseas bonds in May. Their central banks have been spending reserves and raising rates to mitigate their currencies’ fall and prevent defaults without success.

As of August, their reserves had shrunk by $379 billion this year, and Pakistan and Ghana have been negotiating with the International Monetary Fund after losing some 30% of their reserves.

Meanwhile the European Central Bank as well as central banks in Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK, as well as Indonesia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Turkey, are pursuing tightening.

The fact that an estimated 40% of the $28.5 trillion in annual global trade is priced in US dollars and the Bank for International Settlements estimates dollar debts owed by borrowers outside the US at $13 trillion in 2021, all suggest that a debt crisis looms – as it did during the 1980s.

Volcker added that though he anticipated the Mexican debt crisis before it materialized in 1982, he did not think that lowering rates by 1-2 percentage points in 1981 would have prevented it. However, by July 1982 he had changed his mind, and eased monetary policy.

The weakening of American industry because of the strong US dollar contributed to the change in policy, though Volcker thought it was “strange and paradoxical” that the dollar continued rising until 1985. However, he did anticipate that a “sickening fall in the dollar would come” – which it indeed did between 1985 and 1987, the dollar index plunging 50%.

He noted too that to be successful, central banks’ monetary tools were not enough to lower inflation quickly: To absorb the liquidity that led to the high inflation on the late 1970s, early 1980s, reducing the budget deficit should have complemented the Fed’s policies.

Volcker added that this “would have relieved the pressures on our own money and capital markets and our dependence on foreign capital; effective effort to restore budget balance could [have] reinforced what we were trying to do.”

It took time for both the easing of monetary policy in 1982 and for the changes in fiscal and regulatory policies to stabilize the US economy and lower the inflation rate to 5% in 1984, and to 4% in 1987, the year of Volcker’s departure.

As to the dollar: In 1985, the US dollar index was at 160, up from 80 in 1980. This led to his observation that “increases of 50% and declines of 25% in the value of the dollar or any important currency over a relatively brief span of time … are a symptom of a system in disarray.” The disarray led to the Plaza and Louvre accords (1985, 1987) – after which the dollar index dropped from 160 back to 80, its level in 1980.

US industries restored their strength during these upheavals helped by both then-US president Ronald Reagan’s fiscal and regulatory policies and the large increase in hedging instruments developed in the financial market – by now standing at hundreds of trillions in notional value. The latter allowed US companies to stay in their lines of business and mitigate the impact of volatile exchange rates.

However, currency hedging is not just costly and in some countries prohibitively so, preventing companies access to credit and grow, but it brings a misallocation of talents in a floating world. Brains and capital are allocated to an expanding financial sector, and less so to Main Street.