Ukraine war risk and the gold hedge – Asia Times

Subscribe now , for access at a special price of only$ 99/year.

Ukraine conflict risk and the silver hedge

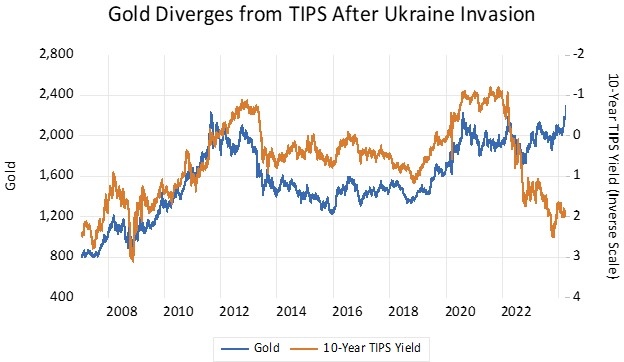

The recent spike in gold prices is analyzed by David P. Goldman, who attributes it to a number of factors, including political risks, governmental challenges faced by major industrial nations, and central banks activities.

Russia is thinking about Ukraine’s upcoming corporate decisions.

James Davis discusses the Russian airstrikes against Ukrainian system and the increase of Soviet air strikes in the Avdeyevka and Bakhmut regions of Ukraine.

US to China: Quit working so hard

Scott Foster writes that Janet Yellen’s new criticisms of China’s export-driven growth design and her support for financial protectionionism are both echoes of Trumponomics.