Unmasking Russiaâs military soft spots in Asia

Russia faces four potential military problems in the Indo-Pacific:

- Vulnerability of the sea leg of its nuclear triad as part of the Pacific Fleet;

- Escalation of tensions around Japan’s territorial claims to the Kuril Islands;

- Large-scale regional armed conflicts, primarily on the Korean Peninsula, but also around Taiwan or in the South China Sea, and between India and China;

- Shifts in strategic trends between Russia and China, and between Russia and India.

Russia’s regional security outlook revolves around these four problems.

The future deployment of intermediate-range missiles in the region by the United States and its allies (especially Japan and the Republic of Korea) is a direct threat to Russian strategic nuclear forces. These missiles could also lead to a clash in the Kuril Islands due to aggressive actions by Japan.

The US Army and US Marine Corps both have programs nearing completion (LRHW Dark Eagle and SMRF Typhon for the former, and uncrewed Long Range Fires launchers for the latter).

Japan is also actively developing such capabilities (including in the hypersonic domain), and the Republic of Korea has already fielded such weapons, namely the advanced missiles of the Hyunmoo family.

The integration of early warning and space situational awareness systems by the United States, Republic of Korea, and Japan should be considered in the same context. In the long term, this will likely result in the buildup of joint and integrated air and missile defense, as well as counterspace capabilities, including through the development and forward deployment of new land- and sea-based missile defense capabilities by those countries.

Meanwhile, the Australia-United Kingdom-United States trilateral partnership (dubbed AUKUS) – which will equip the Australian Defense Force with nuclear-powered submarines and long-range precision weapons and strengthen Australian anti-submarine warfare capabilities – will further increase threats to both the submarine and surface forces of the Russian Pacific Fleet.

Australian submarines will free up US Navy forces and assets to counter the Russian Navy and, possibly, patrol in the Northern Pacific themselves. The fielding of increasingly capable anti-submarine warfare patrol aircraft also contributes to increasing vulnerabilities for Russia.

None of these developments has been explicitly labeled “anti-Russian,” but capability matters more than policy.

Adversary pressure in the immediate vicinity of the Russian sea, air and land borders in the Indo-Pacific is also maintained by freedom-of-navigation operations, flights of bomber aircraft (within the so-called Dynamic Force Employment doctrine) and reconnaissance flights by the United States and its allies – including during exercises and tests of Russian strategic nuclear forces.

The United States’ and allies’ interests in establishing and enforcing so-called “air defense identification zones” – a fictional concept that often leads to media headlines about “airspace violations” – create additional pressure.

The “materialization” of US extended nuclear deterrence, expressed not only in a declarative “nuclear umbrella” for allies, but also in the possible forward deployment of nuclear warheads, adds another dimension to these problems.

Moreover, there seem to be changes to the way extended deterrence operates. US nuclear capabilities protect “US allies and partners,” but the latter’s conventional forces are developing a role in facilitating and supporting US missions involving nuclear weapons.

To put it more bluntly: enhanced and expanded allied non-nuclear capabilities now enable US nuclear missions, aligning with the new US concept of integrated deterrence.

As for possible armed conflicts in the region, be it in the Korean Peninsula, Taiwan Strait, South China Sea or South Asia, each would have a direct effect on Russia as a Pacific country.

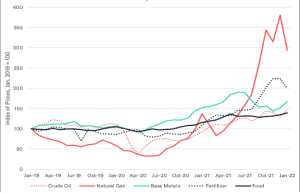

The consequences of such conflicts would lead to dramatic changes in supply chains (which already face immense pressure due to the breakdown of relations between Russia and “the West”), the shake-up of the regional markets (which are increasingly important for Russian exports and imports) and migration waves.

The result would have direct effects on the Russian economy. The effects would be even greater because of the inevitable involvement of China, Russia’s strategic partner.

So far, Russia has managed to maintain relatively stable and even fruitful relations with both China and India. Its relationship with Japan suffers, however, and the relationship with the Republic of Korea will probably follow suit – due both to Seoul’s ever-growing involvement in providing military industrial support to Western countries and to Moscow’s possible cooperation with the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

To be sure, the future of Russia-China and Russia-India relations will depend not only on Moscow, but also on Beijing and New Delhi. Given increasing strategic tensions – augmented by the United States’ interest in rallying India to the US side against China as well as in limiting Russia-India cooperation – established strategic relations might evolve.

These changes might not lead to direct military conflicts but could well drive Moscow to greatly re-prioritize Russian military development.

Russia’s military security depends squarely on the Russian Far East. The Pacific Fleet has the most advanced SSBNs of the Borei family. New surface ships and submarines with Kalibr cruise missiles are entering service.

Anti-ship and air/missile defense missile batteries are deployed to the Kuril Islands and throughout the region. And even a new heavy bomber regiment might be established. The Russian Navy and Long-Range Aviation also routinely hold joint patrols with their Chinese counterparts.

Furthermore, the deployment of US-made intermediate-range, ground-launched missiles in the region (which seems inevitable) would mean the so-called “moratorium” on such weapons no longer stands, and Russia will likely deploy similar capabilities as well, with everyone’s security undermined.

But Russia has bigger vulnerabilities, in that it lacks general-purpose naval forces: submarines, surface ships, and aviation. At this point, it is unclear if the Russian defense industry can address this problem in view of the priority it gives to the Western front. Growing military-technical cooperation with China might offer a solution, however.

Still, if Russia wants to remain a relevant military power both in the region and globally, Moscow must do more. Otherwise, even the ability to sustain the regionally deployed elements of its nuclear triad will be questioned – both by adversaries and partners.

Dmitry Stefanovich ([email protected]) is a research fellow at the Center for International Security, IMEMO Russian Academy of Sciences.

This article was first publishled by Pacific Forum. Asia Times is republishing it with permission.