A passion for wine in Vietnamâs Central Highlands – Southeast Asia Globe

The climate of Vietnam’s Central Highlands, rising high above the country’s muggy coast and river deltas, wasn’t lost on erstwhile French colonists. In the early 20th century, seeking relief from tropical lethargy and illness, they carved a health resort from pine forests at 1,600 metres elevation. They named it DaLat.

As it turned out, apart from íts benefits for well-being, DaLat was a great place to grow things that didn’t do well at sea level. Vegetables and fruits like avocados, artichokes and strawberries thrived in the cooler climate. So, too, did flowers: orchids, roses, hydrangeas. Coffee farms and cashew orchards proliferated on the steep-sided mountain slopes.

Much to the gall of the Gauls, however, grapes didn’t do as well. French being French, they loved their wine, and they had high hopes that the upland climate might yield something akin to the Vitis vinifera of their European homeland: A merlot, perhaps. A robust cabernet. A crisp sauvignon blanc.

Through many fits and starts, they finally have it, although the French colonists (obviously) are long gone.

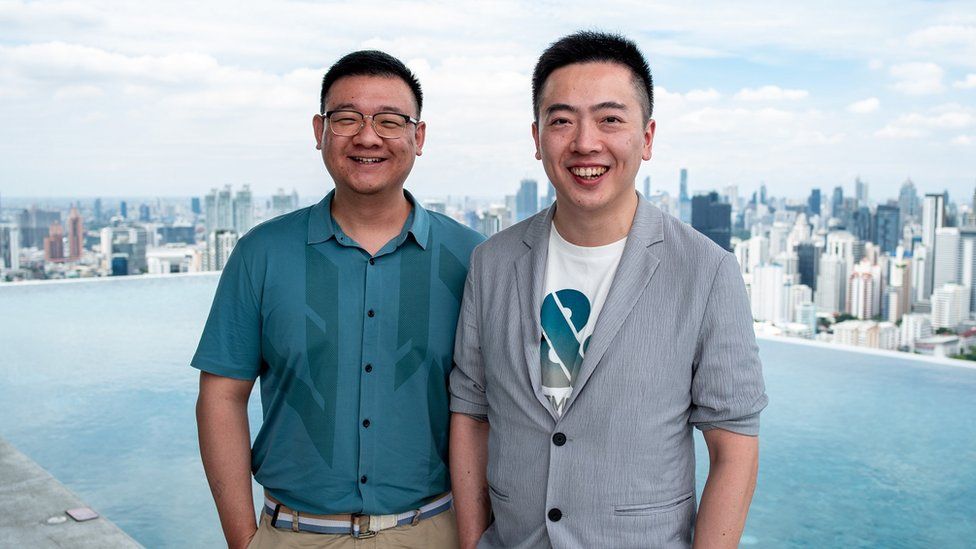

Today the Ladora Winery, operated by Ladofoods, is firmly established in greater DaLat. Its wines may not be to the taste of many Westerners, but as wineries go, it is the “only one with a proper vineyard and winemaking”, affirmed Tu Lê Huy, president and co-founder of the Saigon Sommelier Association. Indeed, Ladora is the only start-to-finish winery anywhere in the former French Indochina.

Ladora grows its own grapes and processes its own wines. The grapes — cabernet sauvignon, shiraz, merlot and sauvignon blanc, plus the hybrid Cardinal varietal — are grown in 125 hectares of vineyards near Phan Rang, not far from ancient Champa Empire ruins. Immediately upon their twice-yearly harvest, they are trucked 60 kilometers to the Ladofoods factory to be de-stemmed, crushed, fermented, pressed, filtered, aged and bottled.

The French had found the local grapes to be far too tart for wine. Even with vineyard cuttings from Europe, the heat and humidity produced only low yields of bitter berries. So they turned their attention to making sweeter fruit wines, especially apple and strawberry. (The Vietnamese already knew that tropical fruits, including bananas and pineapples, could be fermented to produce a high-proof if barely palatable household plonk.)

Upon the normalization of diplomatic relations with the West in the 1990s, wine grapes made a reappearance in Vietnam, boosted by Australian and European investment and modern technology. The key to success was planting in a different climate zone than the production facility.

“DaLat is too rainy, too fertile for grapes,” said Huy, one of three Vietnamese men who founded the sommeliers’ group in 2017. (It has now grown to 120 members.) “DaLat is great for tea and coffee, but not good for grapes. That’s why Lado grows its grapes in Ninh Thuan province.”

Wine in Asia

Elsewhere in Vietnam, Hanoi’s MAM Distillery, established in 2019, blends rice wine with fermented fruit juices, 15 in all, kumquats to raspberries to lemons. Sơn Tinh, founded in Hanoi by a Swiss winemaker in 2000, makes a small-batch rice wine noted for its herbal qualities.

The DalatBeco wine company, launched in 2007, has been importing fruit from France to counter struggles with the quality and consistency of grapes produced by local growers, despite a joint-venture partnership with wine experts in Avignon. “A lot of bulk wine importers bottle their own wine here,” Huy noted.

The nearest full wineries to southern Vietnam are 1,000 km from DaLat, in Thailand’s Khao Yai hills northeast of Bangkok. (Cambodia has a fruit winery at Battambang.) Other Asian countries are slowly progressing.

One of their champions is American wine educator and author Liz Thach, a certified Master of Wine and a professor at California’s Sonoma State University.

“I am pleased to see the growth of wineries in Asia, along with consumer interest in wine,” Thach said. “China actually has a very old wine culture and over 400 wineries, with some of them producing excellent award-winning wines. Bali now has four wineries, and I recently visited one of them and was extremely impressed with the quality of the wine.

“Vietnam has also been producing wine for many years, and they have become very creative in pairing wine with the delicious Vietnamese cuisine. Wineries are growing in number in Thailand, Japan, Korea and India. I believe there is an exciting future for wine in Asia.”

Huy was less enthusiastic about Chinese wine than Japanese. “China is still very much in the early stage of winemaking,” he said. “I tried some; it still has a lot of tannin and lacks character. But Japan makes some nice whites, which they’ve crossed with native grapes suitable to the climate.”

Profit and projection

From a profitability standpoint, wine is far from big business in Vietnam. Consumption of imported wines far exceeds domestic brands, yet in 2023, the market yielded only US$229 million, about $2.30 per capita. (By contrast, U.S. wine revenue was over $56 billion, with per capita consumption of about $58.) Continued growth in the Vietnam wine market is anticipated at a rate of just under 4 percent per year through 2027.

Figures from Ladofoods highlight the fallout the domestic industry experienced in 2022 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Vietnam’s leading wine producer netted US$10.15 million in sales in 2021, yet that figure plummeted to $7.85 million in 2022. It’s likely that 2023 will show a recovery to more than $9.2 million (223 billion in Viet Nam Dong).

About 40 percent of Ladora’s production is exported to other Asian countries, said tasting-room manager Ngoc Dung. Of that, Japan gets the lion’s share, followed by Korea. Lesser amounts are shipped to Thailand, Cambodia, Malaysia, Singapore, Laos, China and Taiwan. That leaves 60 percent for the domestic market.

“The Vietnam market is definitely an entry-level market,” said Huy. “They are only starting to get the idea of wine pairing. There’s a niche market of well-educated and really wealthy Vietnamese for whom classic Bordeauxs are number one.

“They’ve started to drink white with seafood. But for the most part, white wine is not working well here. It’s better in the north because North Vietnamese have a different palate. They like more acidity but not sweet. Central Vietnam likes more spice. The South likes sugar.”

A visit to Ladora

The Ladora Winery is located 28 kilometers east of DaLat city in the hill country of the Phat Chi district. The elegant Chateau DaLat, sitting atop a garden knoll, is at the heart of a building complex overlooking a landscape of greenhouses that provide colourful flowers to the markets of DaLat and Ho Chi Minh City.

Twenty-five steps beneath an earth-covered hummock is an elaborate and extensive wine cellar. Oak barrels filled with aging cabernet sauvignon, shiraz and merlot, and stainless-steel drums of sauvignon blanc, are stacked against the walls. A tower of unlabeled bottles of reds occupies the middle of one room. A long tasting table awaits tour groups, not present on this day.

Assistant winemaker Nguyen Lan said the company makes two principal kinds of wine with these same grapes, for two distinct markets. The Chateau DaLat brand is designed for those of European predilection; wines are plus or minus 12 percent alcohol. Vang DaLat, its grapes blended with the hybrid Cardinal varietal, is typically over 15 percent. (Ladoro also makes a sweet but lower-alcohol Nouvo Sangria and a sparkling Vivazz fruit wine.)

“Mostly, Asians like the sweeter wines,” Lan said. “So we add mulberries, whose sugar increases the alcohol content while making the colour a bit lighter.”

“In DaLat, there’s just not enough sugar in the natural wine,” sommelier Huy reiterated. “The mulberry adds more sugar and more colour.”

Europeans, by contrast, prefer the unblended Chateau DaLat varietals, made under the direction of head winemaker Lê Binh together with European consultants. Some of these have been honoured at wine competitions in Hong Kong and San Francisco.

A sample tasting

A visit to Ladora’s sophisticated, Czech-designed tasting room begins with a video presentation introducing the Ninh Thuan vineyards. The company owns one-fifth of the grapes here; the remaining 100 hectares belong to private farmers contracted to sell the grapes to Ladora. Drip irrigation ensures the plants have sufficient water in the dry season. Flocks of ducks patrol the wine hedges to eat insect pests.

Annual grape production averages 10 to 15 tonnes per hectare, Lan said. All of the fruit is transported uphill to the modern Central Highlands factory, where the temperature is maintained at a steady 18 to 20 degrees Celsius.

It would be impossible to taste each one of the more than two dozen wines in the Ladofoods catalogue in a single sitting. A sample tasting is more instructional than comprehensive. The 2017 Chateau DaLat Special sauvignon blanc (12.5 percent) is very dry, a little sour, with aromas of lime and passion fruit. It’s recommended to be enjoyed with shellfish.

The Vang Dalat Classic Special is a 70-30 blend of Cardinal grapes with mulberries. Despite high acidity and peppery spice, it has a mellow finish. “It’s my favorite,” said the assistant winemaker. Vang Dalat Strong, at 15 percent alcohol, is an 85-15 blend of Cardinal and mulberries with a lighter ruby colour and the aroma of sweet berries, almost like jam on bread. “Korean guests love this one,” Lan said. Because of their mulberry content, the Vang Dalat wines don’t carry a vintage date.

More traditional in approach is the 2018 Chateau Dalat Reserve cabernet sauvignon (12.5 percent), aged in French-made American oak barrels for 1½ years. A subtle flavour of black currant presides over a gentle red that retails at US$14. Aged six months longer, the 2019 Chateau Dalat Signature shiraz (13 percent) is earthy and full-bodied with rich tannins and a white-pepper finish. Its retail price is US$34. “Japanese and Koreans love this one,” said Lan.

“Most people in Vietnam have the idea that import wine is better than wine from Vietnam,” the assistant winemaker said. “So it’s hard to change their mind.”

Of course, not all Vietnamese are enamoured with their country’s domestically produced wines. Lê Huy, the sommelier, suggested that they lack originality: “Welcome to the government company,” he laughed. (Formerly state-owned, Ladofoods is now in fact a Vietnamese joint stock corporation.)

Looking ahead

Today, as a picturesque city of nearly half a million people, Da Lat is a favorite of tourists both domestic and international. It remains a health resort as well as a center for education, its universities famed for their work in biotechnology, nuclear physics and architecture. Beautiful gardens surround its urban lakes. A street market is renowned throughout Vietnam.

But there are no winery tasting rooms even though there is apparently no prohibition against them. DaLat wines are widely available in shops in that city, and in Ladofoods’ showroom in Ho Chi Minh City, but consumers have no chance to taste the wines before buying them. It seems that someone is missing a great great marketing opportunity.

Foreign investors have looked into the possibility of establishing other wine regions in Vietnam. But Huy said it’s unlikely that will happen.

“In the North, we don’t have a delta big enough for vineyards,” he said. “It’s only rocks.

“The BaNa Hills near DaNang are very suited for wine grapes, but the best climate is in the middle of a national reserve — and money cannot talk in the national reserve. There was interest from an Italian winemaker, but the wine would have had to be priced at US$70 a bottle. There would be no way to sell it.”