Volume One 2024 magazine out now | FinanceAsia

We are delighted to announce that the first volume of FinanceAsia’s 2024 bi-annual magazine, is now available for your perusal.

In this edition, we celebrate all the winners the FinanceAsia Achievement Awards 2023 and explain the rationale behind why each institution won. In addition to the Deal and House Awards for Asia and Australia and New Zealand (ANZ); this year we added a new category, the Dealmaker Poll, which recognises key individuals and companies based on market feedback.

In feature format, Christopher Chu examines the potential and reach of artificial intelligence (AI) in Asia – the fast-moving technology is presenting both huge challenges and opportunities for investors. While it remains caught in the cross-hairs of geopolitics and regulation, he examines how AI could be a game-changer for productivity.

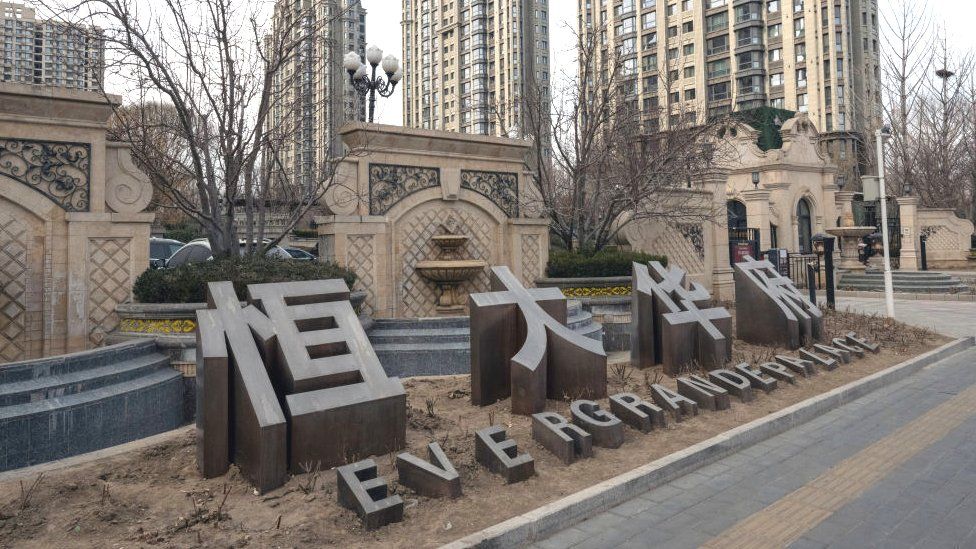

Ryan Li explores the proposed breakup of Chinese giant Alibaba and how the firm’s ambitions fit in with wider developments across China’s tech sector.

Also in the magazine, Andrew Tjaardstra reviews IPO activity across key Asian markets in 2023 and looks ahead to how public markets might perform in 2024 – while it certainly hasn’t been an easy ride for the region’s equity markets over the last 12 months, there have been some bright spots, notably India and Japan, which are set to continue their momentum this year.

Finally, read Ella Arwyn Jones’ exclusive interview with Rachel Huf, the new Hong Kong CEO of Barclays. Huf shares her transition from lawyer to leader, offering insights around her career path and the strategic direction of the bank in the Special Administrative Region (SAR) over months to come.

¬ Haymarket Media Limited. All rights reserved.