China tech giants offer upside surprises

As Chinese Communist Party leaders gathered at the beach resort of Beidaihe in recent days, the many storm clouds on the horizon were impossible to ignore.

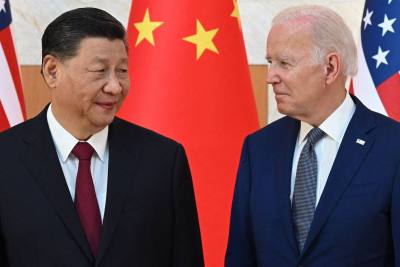

Between an economic slowdown, deflationary forces, new property market distress and ongoing hostilities with the West, Chinese leader Xi Jinping has a full slate of headwinds with which to contend.

Yet it’s worth noting key areas where Beijing is picking up potentially powerful tailwinds, too. Despite the various sources of turbulence, Chinese tech earnings are racking up some impressive gains.

From Ant Group making a net profit of 13.37 billion yuan (US$1.85 billion) in the three months to March 31, a 17.5% year-on-year jump, to Huawei reporting 2.2% year-on-year growth in consumer business revenue for the first half of the year, there’s reason for optimism that the worst may be over for China’s battered tech giants.

Such signs of hope are badly needed at a moment when US President Joe Biden’s White House is cranking up the punitive pressure on China’s tech firms, nominally in the name of US national security.

Last week, Team Biden banned US investors from investing in sections of China’s chips, quantum computing and artificial intelligence (AI) industries. The step could upend efforts to lift Sino-US ties from their historic lows. Team Xi might retaliate anew.

One interesting wrinkle surrounding this year’s Beidaihe confab is the theme of scientific and tech self-sufficiency.

To amplify the point, invites were extended to a large number of semiconductor and AI experts — at least 57 — on the “forefront of domestic technology.” Such invitations tend to shed light on the concerns that Beijing views as most urgent.

The official Xinhua news agency quoted Xi’s chief of staff Cai Qi saying “We hope all experts … make new and greater contributions to achieving high-level scientific and technological self-reliance.”

On the ground, though, there are myriad signs that China Inc is coming out the other side of the last few years of regulatory crackdowns on tech platforms — and showing convincing signs of life.

Take Alibaba Group reporting a 14% year-on-year jump in quarterly sales in the April-June period despite sputtering mainland economic growth.

All of the key business units of the e-commerce colossus Jack Ma built are returning to life and buttressing the argument that Xi’s wealth and confidence destroying clampdown is in the rearview mirror.

“Big tech earnings may show continued recovery, with profits expected to rise 10.4% year-on-year in 2Q,” says Marvin Chen, an analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence.

This was the pledge that Premier Li Qiang made in March when he became Xi’s No 2 official and financial reform enforcer.

News that the domestic commerce unit of Alibaba — ground zero of Xi’s tech clampdown in late 2020 — is now producing about $16 billion in revenue, a 12% rise year on year in Q2, seems indication enough that China’s Big Tech may be ready to shift into higher gear.

The bold corporate overhaul Alibaba announced in March is by all indications off to a solid start. China’s online commerce leader announced plans to split its $220 billion empire into six business units, a major restructuring that promises to yield several initial public offerings (IPOs).

The breakup frees up Alibaba’s main divisions from e-commerce and media to the cloud to operate with far more autonomy, laying the foundation for future spinoffs and market debuts that create fresh wealth and jobs.

The maneuver also offers a blueprint for other tech giants to navigate around regulators’ efforts to curb monopolistic behavior among internet platforms. As Neo Wang, analyst at Evercore ISI, puts it, the six-way split-up could “serve as a template for Alibaba’s peers.”

Since November 2020, when regulators clamped down on Ma’s empire, Baidu, Meituan, Tencent and a who’s-who of Big Tech names have felt the monopoly-curbing, regulatory heat.

Yet it was Ma’s Ant that bore the initial brunt of the market-shaking putsch. Beijing regulators pounced in particular on Ma’s plans to take his fintech unit public, a planned $37 billion IPO that would have been history’s biggest.

Rather than listing in New York, as Alibaba did in 2014, Ant was to sell shares in Shanghai and Hong Kong. The IPO had promised to raise the Greater China region’s status as a tech and finance superpower.

Now, as economic growth stalls and property woes dangerously fester, Team Xi needs to lean into these tech green shoots to strengthen the tailwinds coursing through the economy.

Since March, Premier Li has been linearly focused on catalyzing more scientific and technological innovation and affording the private sector more space to grow and create well-paid jobs.

According to Li’s plans, Beijing regulators are going easier on tech giants and supporting the development of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSME) to address record youth unemployment, which hit a record 21.3% in June, without relying on large-scale stimulus.

China cut interest rates this week in a move that surprised many analysts and underscored the deepening depths of China’s economic troubles.

“The market was expecting the People’s Bank of China to wait until September before easing again, and [recent] cuts suggest that the authorities’ concern about the state of the macroeconomy is mounting,” says Robert Carnell, head of Asia-Pacific research at ING Bank, said.

A big piece of the economic revival puzzle is reversing Xi’s efforts to maintain the dominance of state-owned enterprises (SOEs). In the years since 2015, the year when Shanghai stocks collapsed, Xi’s response has been to support SOEs to boost economic growth.

Li’s charge now is to diversify the economy away from exports and smokestack industries, which ultimately means incentivizing greater private sector innovation and productivity.

The key will be for Xi to give Li the latitude to get his reform plans dating back to 2013 back on track. A decade ago, Xi pledged to let market forces play a “decisive” role in Beijing’s decision-making.

Since then, though, China has become less, not more, transparent, withholding key data needed for efficient market mechanisms. Indeed, Xi’s recent regulatory crackdowns and other restrictions on private business have made it harder and harder for outside credit ratings companies to assess where China Inc is headed.

Last month, Li said the government is stepping up efforts to normalize China’s regulatory environment. The goal, Li has said, is to “reduce the costs of compliance and promote the healthy development of industry.” He said that “on the journey of building a modern socialist country, the platform economy has great potential.”

In a speech in mid-July, Li told tech chieftains in the audience – including officials from Alibaba Group, TikTok owner ByteDance and food delivery group Meituan – to “push to increase their international competitiveness and dare to compete on the global stage.”

To analyst Kelvin Wong at OANDA, the latest rhetoric from the top man on China’s State Council is “likely to boost positive animal spirits in the short-term at least.”

But Team Xi also must work harder to pull in more foreign capital. “Inbound investment has fallen despite Premier Li’s best efforts to roll out the welcome mat for foreign executives and local government officials crisscrossing the globe in search of new sources of capital,” the Eurasia Group consultancy wrote in a note.

Eurasia Group points out that “multiple factors” have contributed to China’s failure to boost FDI.

“Cash-strapped local governments are unable to offer the generous subsidies and access to free land that they once did. The nationwide push for a ‘unified market’ increasingly discourages preferential treatment or discriminatory policies at the local and provincial levels,” the Eurasia Group report said.

“Domestic firms are becoming formidable competitors in industries such as automaking, narrowing the opportunities for foreign firms in sectors that have attracted a large share of FDI in the past,” the same report said.

“Hawkish signals from Beijing over national security” – including a revised anti-espionage law that went into effect on 1 July – a crackdown on the activities of foreign consultancies and due diligence firms operating in the country, are also denting new FDI, the Eurasia Group said.

That, and other recent moves targeting select multinationals, “have contributed to a deepening anxiety among foreign companies, many of which are weighing China opportunities against third country alternatives as they try to ‘de-risk’ their supply chains in the face of rising geopolitical tensions,” the report said.

Yet recent signals from China’s top tech companies suggest better days lie ahead. Team Xi just needs to accelerate efforts to ensure the virtuous cycle continues.

Follow William Pesek on X, formerly known as Twitter, at @WilliamPesek