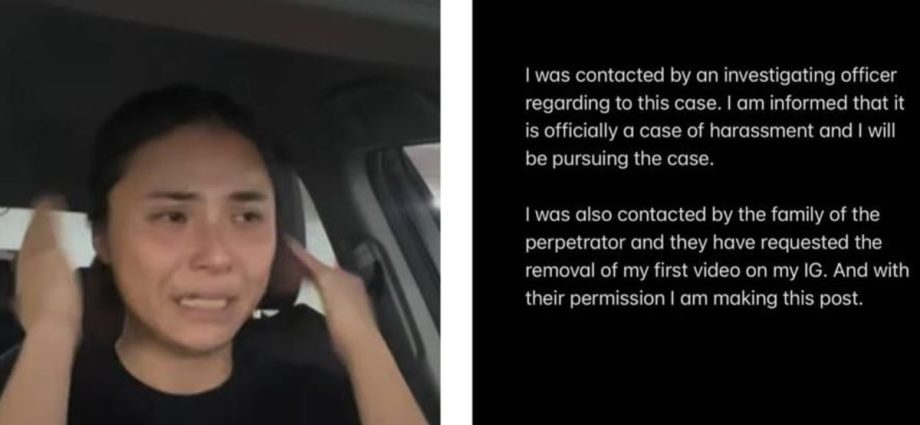

Commentary: What can you do if someone photographs or films you in public without your consent?

IS IT Socially RIGHT, NOT ILLEGAL?

While taking pictures or videos of someone in community is typically not against the law, some people feel that doing so violates their protection and is morally wrong. Similar to this, some people believe that as long as the content is neither offensive nor dangerous, it is acceptable to take pictures and videos of other people in public.

Even if these images or videos aren’t offensive or hazardous, one should still be aware of the potential repercussions on the subjects, particularly a case of unfavorable behavior.

This covers their potential effects on their friends and family, as well as how they might be affected at work or in class. The moral and legal repercussions of taking a picture or photo of someone else in public are finally up to the individual. If the circumstances allow, it would only be appropriate to get permission before taking any video or pictures, especially if they involve a baby.

What can you do if you find yourself the unwitting area of a harmless video or image, then?

Ask the other party to stop taking photos or videos of you as you quietly and politely approach the situation. Additionally, you can request that any previously taken footage and / or photos be deleted. It’s crucial to refrain from yelling, arguing, intimidating, or being hostile.

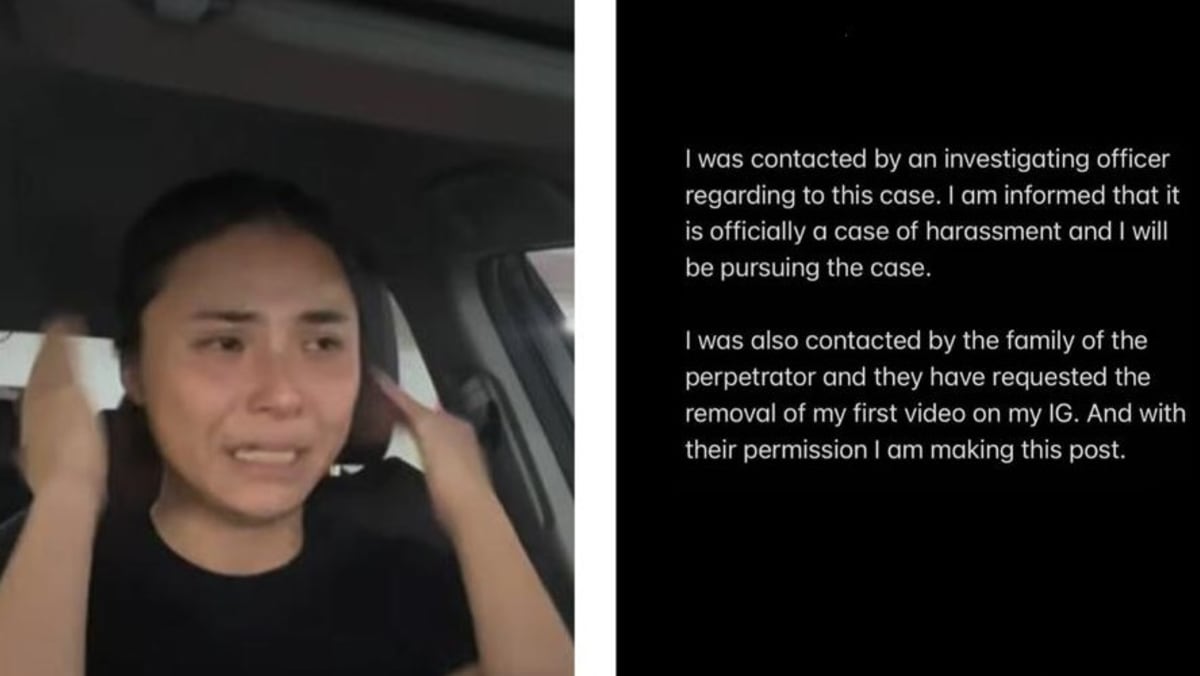

Additionally, avoid getting real with them, such as attempting to steal their products or pushing them hard. You might want to record a statement or call the police if the guy keeps filming or photographing you.

It’s important to realize that you don’t have the right to require their personal recognition files or stop them from leaving, even though you may have specific information from them in order to file your report. You have the option of submitting a judge’s grievance to provide instructions for further action if your police report for the crime has not been investigated or prosecuted. You might also think about filing a lawsuit against the individual for any financial losses or emotional distress they may have experienced.