Europe wants solar power sovereignty from China

Europe generates a lot of solar power, most of it using photovoltaic (PV) modules imported from China. Now, in the name of energy sovereignty, the European Union (EU) and its solar industry firms want to reduce that dependence.

The organizers of the Intersolar Europe 2023 trade exhibition and conference, held in Munich, Germany, from June 14 to 16, put it this way in their introduction to the event:

“PV production is set to return to Europe – with strong political tailwinds. In order to achieve energy sovereignty and make its energy system permanently resilient, Europe must minimize its technological dependencies and supply chain disruptions… Politicians and economists agree: Photovoltaics production must be brought back to Europe.”

That was a follow-up to a statement made last October by European Union Commissioner for Internal Market Thierry Breton when the European Commission formally endorsed the continent’s new Solar Photovoltaic Industry Alliance:

“To meet Europe’s renewable energy objectives — and avoid replacing a dependency on Russian fossil fuels with new dependencies — we are launching an industrial alliance for solar energy. With the alliance’s support, the EU could reach 30 Gigawatt of annual solar energy manufacturing capacity by 2025 across the full PV value chain. The alliance will foster an innovative and value-creating industry in Europe, which leads to job creation here. Europe’s solar industry already created more than 357,000 jobs. We have the potential to double these figures by the end of the decade.”

30GW would be 3.6 times the 8.3GW estimate of European PC module capacity in 2021 issued by Intersolar. More recent data is hard to come by – McKinsey & Company gave a range of 6GW to 8GW in a report issued at the end of 2022, which seems oddly low,

But if Europe’s capacity is currently 10GW, then that would be just 15% of the 68.6GW installation demand forecast for Europe by market researcher TrendForce in February. Most of the rest comes from China.

The EU wants to raise its self-sufficiency in PV module production to 40% by 2030. That might sound like a modest target, but the EU also wants to increase Europe’s total installed solar power generating capacity from a bit more than 200GW in 2022 to 320GW by 2025 and nearly 600GW by 2030.

This will require financing amounting to tens of billions of euros, which will be mostly private but directed and supported by EU policy funds.

Intersolar Europe is part of the so-called “smarter E Europe.” This year, it was held in conjunction with three related exhibitions: ees Europe (batteries and energy storage systems), Power2Drive Europe (charging infrastructure and electric vehicles) and EM-Power Europe (energy management and integrated energy solutions).

The smarter E Europe, which bills itself as “Europe’s largest platform for the energy industry,” promotes renewable energy, the decentralization and digitalization of the energy industry, and coordination of the electric power, heating and transport sectors.

Intersolar Europe 2023 alone attracted 1,372 exhibitors; the combined events attracted 2,469 exhibitors from 57 countries and more than 106,000 visitors from 166 countries.

Exhibitors included manufacturers of solar wafers, cells, modules, PV production equipment, and providers of related services. In addition to the product exhibitions, there were presentations on cell and module technologies and production equipment made in Europe.

While Europe has a legitimate solar power supply chain, it still lacks economies of scale. According to McKinsey & Company, European companies have only 11% of the global market for solar polysilicon, 1% for ingots and wafers, 1% for solar cells and 3% for PV modules.

By 2025, those shares are expected to increase to 12%, 4%, 4% and 5%, respectively. Wacker is the only European maker of solar polysilicon and the only European company in the industry with a significant market share.

However, as noted by Intersolar:

“The European PV industry is already taking action in response to the growing demand. Here are some recent examples: SMA Solar Technology (Germany) is building a 20GW factory for system solutions for large-scale PV plants in Hesse. Inverter manufacturer Fronius (Austria) is investing 233 million euros in expanding its production capacity this year. Belinus (Belgium) is planning 5GW module factories in Belgium and Georgia, respectively, and FuturaSun (Italy) is planning a 2GW module factory in Cittadella (Veneto). Italian utility company Enel is building a 3GW module factory in Sicily and Lithuanian module manufacturer Solitek is investing in a new factory in Italy.”

China is far and away the largest producer and user of solar power, producing close to 80% of the world’s solar silicon, 95% of its solar ingots and wafers, 75% of its solar cells and 70% of its solar modules, according to McKinsey & Company.

More than half of Chinese-made PV modules were exported in 2022, according to PVTIME, and the largest market for those modules was Europe.

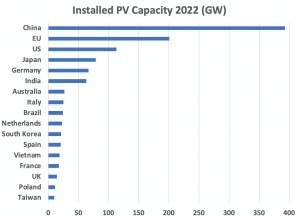

According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), China accounted for 37% of total worldwide installed PV solar energy capacity in 2022, followed by the EU at 19%, the US at 11%, Japan at 7.5% and Germany and India at about 6% each.

Moreover, China is likely to install more than twice as much PV capacity in 2023 as Europe and 3.7 times as much as the US, according to data from TrendForce.

Seven out of the top 10 suppliers of PV modules are Chinese. One is headquartered in Canada but makes most of its products in China, one is American and one is South Korean.

Lists compiled by other market research outfits are slightly different, but all of them show a preponderance of Chinese companies and no European companies except for Q-Cells of Germany, which was rescued from bankruptcy and acquired by South Korea’s Hanwha Group in 2012.

China’s enormous production capacity, supported by a complete supply chain of materials, equipment, production and assembly, gives it unmatched economies of scale and a cost advantage it is unlikely to lose even if Europe reaches its energy sovereignty goals.

The gap is wide: Market research and consulting company Wood MacKenzie reports that Chinese PC modules were sometimes less than half the price of modules made elsewhere in 2022. But issues of energy security and the long-term development of European industry are taking priority over price.

The difference will have to be made up with subsidies and the restriction of imports. Nevertheless, by its own calculations, Europe will remain dependent on China for a large share of the solar power capacity it plans to install for years to come.

On the other hand, the revitalization of the European solar power manufacturing industry should speed up the move away from fossil fuels and contribute to the development of new clean technologies.

The EU aims to scale up production of solar photovoltaic products and components in order to accelerate the deployment of solar power and make its energy system more robust.

The final version of its Solar Energy Strategy, announced last year, names EIT InnoEnergy as the leader of its Solar Photovoltaic Industry Alliance, with Solar Power Europe and the European Solar Manufacturing Council also on its steering committee.

EIT InnoEnergy brings together innovators and industry, entrepreneurs and investors, graduates and employers to facilitate the development of sustainable energy and decarbonization. It supports education and invests in start-ups and companies with untapped growth potential. So far, it has invested in about 180 companies.

SolarPower Europe is an association with some 300 members that connects policymakers and the solar industry. The European Solar Manufacturing Council represents the interests of the European PV manufacturing industry.

Follow this writer on Twitter: @ScottFo83517667