The coming US-China financial divorce – Asia Times

The United States and China’s economic ties no longer pose a hazard in the future. It is formalized, moving, and deeply disruptive around. Understanding this novel time is crucial for investors because it is not recommended.

More than just a business skirmish, the broad tariffs on Chinese imports have now been passed into law. They represent a traditional shift in the world’s supply chains, scientific ecosystems, and capital flows.

It’s not just about economy here. Control and financial power are both at play here. Investors may then adjust to a world where the fundamental principles of international commerce are being restored quickly and under pressure.

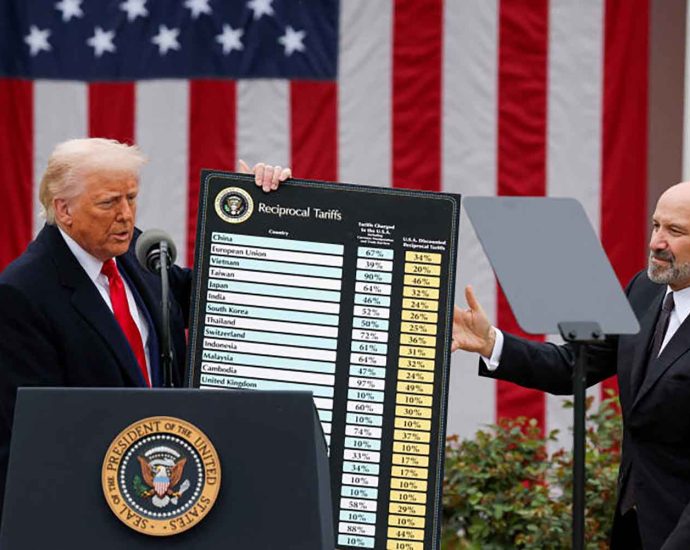

President Trump signed a broad common 10 % tax on all imports on April 2, which would increase to an extraordinary 60 % on Chinese products. These new taxes are atop an already formidable 85 % tax roof, which results in total costs of 145 % on Chinese exports to the US.

Beijing launched the initial volleys of retaliation, including banning the trade of crucial minerals that are vital to the American tech and aerospace sectors, as soon as supply chains started to splinter, and cost pressures raged across industries.

The two largest economy of the world are currently at odds with one another structurally, not in terms of strategy. Although the term” Cold War” is frequently overused, it is becoming more difficult to ignore the parallels. Realizing this is the end of the long-held notion that economic integration would act as a buffer against political issue.

What do a full-fledged economic divorce entail?

First, cash flows will become more and more polarized. Will more and more restrictions and attention been placed on dealings between American and Chinese entities, which were once thought to be routine. Actions with a dollar denomination may be restrained. US pension finances, university endowments, and index-linked ETFs could confront direct restrictions or growing political pressure to sell from Chinese goods.

This could lead to a flood of delistings from US exchanges, more stringent CFIUS reviews, and more inbound investment controls aimed at specific industries. Trump’s officials are now sending out clear warnings that the US government should not be “funding China’s fall.”

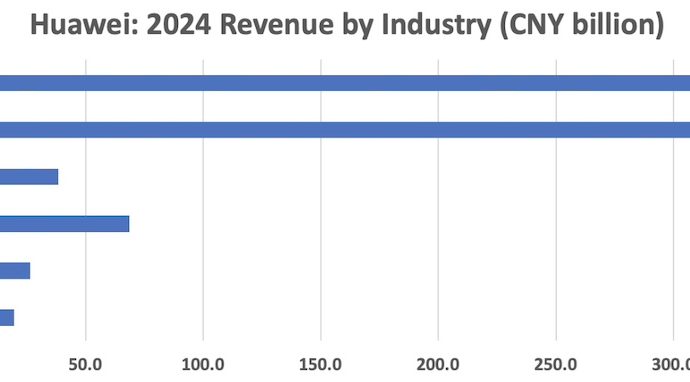

Next, the technological gap may grow and grow bigger. Firms like Huawei, ZTE, and DJI were put under a lot of stress in the past. Focus is now turning more and more toward AI, semiconductor manufacturing, clean energy platforms, and the next-generation industries. Washington is moving to wall away full innovation ecosystems, not just to limit exports.

Hope tighter registration standards, more stringent investment restrictions, and more drastic sanctions against Chinese businesses as well as those of allies that have close ties with Beijing. This is about granting China access to fundamental capabilities while imposing technical dominance.

Third, the very foundation of international funding is being challenged. The dollar-based method has been the natural arbitrator of global commerce for decades. That independence is diminishing.

China is aggressively promoting the yuan internationalization in anticipation of limits on its currency’s exposure. Its Cross-Border Interbank Payment System ( CIPS) is being touted as a SWIFT alternative, aiming to make a competing financial system less reliant on Western sanctions.

The development of parallel financial systems will alter the flow of capital, restructure trade agreements, and add new layers of complexity to currency markets.

This transition may bring volatility but even opportunity for investors.

On the one hand, nations that are close to the United States will be a source of corporate capital. As businesses expand their manufacturing operations away from China, there are already important outflows from India, Vietnam, Mexico, and some parts of Eastern Europe.

Reshoring and friendshoring, once considered commercial words, have evolved into obvious government policy, supported by strong economic bonuses and political will. On the other hand, China is repositioning rather than retreating.

President Xi Jinping’s effective romance of the Global South highlights Beijing’s plan to strengthen relationships with developing countries that are under pressure from American isolationism.

Through partnerships in 5G, AI, clean energy, and superior production, Xi’s new visits to Vietnam, Malaysia, and Cambodia, which are nations that are directly impacted by Trump’s tariffs, highlight Beijing’s effort to integrate these nations into its sphere of influence.

Buyers must be aware that this is no longer about military tariff fights or headline-driven ruckus.

It’s about a fundamental restructuring that will affect every aspect of index content, foreign exchange approach, ESG frameworks, and capital allocation. The outdated notion that industrialization was a push invincible is being broken down in front of us.

The speed behind the economic divorce suggests it is about to become inevitable, even though it is not yet final. And like with any sloppy isolation, fortunes will be made not by those who react physically, but by those who anticipate where assets, impact, and opportunities may flow when the ancient household is split.

The discerning investment will be guided by a mastery of the fresh rather than a return to the old.