Global depopulation: saving the Earth while killing the economy? – Asia Times

Right now, animal community development is doing something much thought impossible – , it’s hesitating. It’s then possible world population was top much earlier than expected, topping 10 billion in the 2060s. Therefore, it may begin to fall.

In wealthier states, it’s currently happening. Japan’s population is falling quickly, with a net loss of 100 people every minute. In Europe, America and East Asia, fertility rates have fallen quickly. Some developing nations with lower or middle incomes are on the verge of a decline.

This is an amazing change. Practitioners had predicted that our figures, which were away from around 8 billion immediately, could reach 12.3 billion ten years ago.

Some campaigners have tried to save the setting by halting world population growth for the past 50 years. In 1968, The Population Bomb forecast large epidemics and called for large-scale baby power.

Population growth is slowing without community control, and rich countries ‘ populations are declining, triggering furious but largely inefficient efforts to encourage more babies. What might the culture be affected by a declining global people?

Depopulation is currently happening

For much of Europe, North America, and some of Northern Asia, emigration has been live for centuries. While longer life expectancies mean that the proportion of very old people ( over 80 ) will double in these areas in the next 25 years, fertility rates have steadily decreased over the past 70 years and have remained low.

China was until lately the world’s most populous state, accounting for a fifth of the global community. But China, too, is then declining, with the drop expected to quickly expand.

By the end of the century, China is projected to possess two-thirds fewer people than yesterday’s 1.4 billion. The long neck of the One Child Plan, which ended in 2016, is to blame for the unexpected fall, which was too late to stop the decline. Japan was once the country’s 11th most filled state, but is expected to reduce before the end of the century.

What’s going on is known as statistical change. As countries move from being mostly agrarian and agrarian to business and service-based economies, reproduction drops quickly. Communities begin to decline when low birth rates and lower fatality rates combine.

Why? Option is a significant factor. People are having more children later in life and, on average, have fewer because of better options and freedoms in terms of learning and careers.

Why are we immediately focused on emigration, given birth rates in wealthy countries have been falling for years? Most countries experienced a slight decline in birth rates before the Covid pandemic hit in 2020, while fatality rates rose as well. That strategy helped to accelerate the general trend of people drop.

A falling people poses real difficulties financially. There are fewer personnel accessible, and more senior citizens require assistance.

Countries in rapid decline may begin to halt migration to ensure they stay the fewest workers at home and stop the population from getting older and declining. The need for qualified employees will grow worldwide. Of course, migration does n’t change how many people there are – , just where they are located.

Are these all prosperous country problems? No. People rise in Brazil, a huge middle-income state, is now the slowest on record.

By 2100, the earth is expected to have just six states where babies outweigh deaths – Samoa, Somalia, Tonga, Niger, Chad, and Tajikistan. The other 97 % of the world’s fertility rates are thought to be below replacement levels ( 2,1 children per woman ).

Bad for the business – , good for the environment?

Fewer of us means a break for character – , correct? No. It’s not that easy.

For example, the per capita energy consumption rate drops between 35 and 55, then drops, and then rises again at age 70 as a result of older people’s longer-term indoor habit and living only in larger homes. Population declines caused by population declines could be offset by this century’s incredible population growth.

Then there’s the great gap in reference use. Your carbon footprints is nearly twice as large as it is for residents of the United States or Australia, the world’s biggest total transmitter.

Eat more in wealthy nations. Therefore, it’s good that more of the world’s population will be higher emitters as more countries become wealthier and healthier but with fewer kids. Unless, of course, we decouple financial rise from more pollution and other economic costs, as many countries are attempting – but very carefully.

Hope more lenient immigration laws to increase the number of people who are working. This is already happening; movement has now past projected levels for 2050.

Migration to a developed nation can be useful for both the new country and the country where they were born. Environmentally, it does improve per capita emissions and economic effects, given the website between income and emissions is pretty obvious.

Then there’s the looming tumult of climate shift. As the planet heats up, forced movement– where people have to leave home to avoid drought, conflict or another climate-influenced disaster – , is projected to jump to 216 million people within a quarter century. Forced movement may change pollution patterns, depending on where individuals find shelter.

Putting all of these things away, it’s possible that a declining global population will lower overall consumption and lessen the strain on the environment.

Environmentalists have long hoped that the world’s population will decline despite concerns about urbanization. They might shortly receive their wish. Not through imposed baby control laws, but mainly through the options of educated, wealthy women choosing to live in smaller families.

Is whether declining population may lessen the pressure on the environment remains a mystery. This is not a guaranteed outcome unless pollution reduction and consumption patterns change in developed nations.

Andrew Taylor is associate professor in population, Northern Institute, Charles Darwin University and Supriya Mathew is postdoctoral scholar in climate change and health, Charles Darwin University

This content was republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original content.

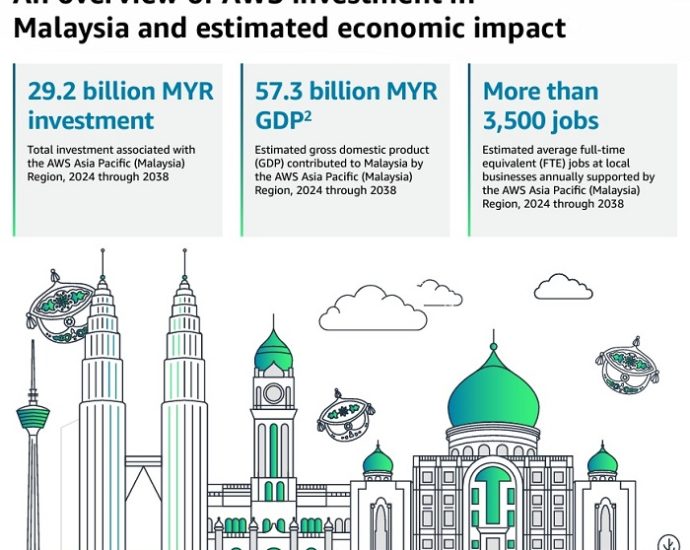

The new AWS Region in Malaysia, led by Prasad Kalyanaraman ( pic ), vice president of infrastructure services at AWS, enables organizations across Asia Pacific to fully exploit the potential of the world’s most extensive and reliable cloud, assisting customers in deploying advanced applications with a wide set of AWS technologies like AI and ML. With today’s release, AWS is happy to support Malaysia’s modern transformation and help promote its function as a local hub for AI”.

The new AWS Region in Malaysia, led by Prasad Kalyanaraman ( pic ), vice president of infrastructure services at AWS, enables organizations across Asia Pacific to fully exploit the potential of the world’s most extensive and reliable cloud, assisting customers in deploying advanced applications with a wide set of AWS technologies like AI and ML. With today’s release, AWS is happy to support Malaysia’s modern transformation and help promote its function as a local hub for AI”.

.jpg) fabric roads, and proximity to key local data systems. ” Johor offers a unique blend of communication, system, and ability, making it an ideal place for our latest data center campus”, he impressed.

fabric roads, and proximity to key local data systems. ” Johor offers a unique blend of communication, system, and ability, making it an ideal place for our latest data center campus”, he impressed.

Additionally, he highlighted the emergence of a circular economy to facilitate long-term sustainability, as being a growing trend: “Look at the battery ecosystem for example, a huge industry is developing around the recycling of batteries – additionally the recycling of solar panels, turbines and so forth is being considered. The recycling industry is becoming larger as ultimately, unless there is a circular economy around it, resources will be wasted. New action is being taken to develop a fully circular product lifecycle.”

Additionally, he highlighted the emergence of a circular economy to facilitate long-term sustainability, as being a growing trend: “Look at the battery ecosystem for example, a huge industry is developing around the recycling of batteries – additionally the recycling of solar panels, turbines and so forth is being considered. The recycling industry is becoming larger as ultimately, unless there is a circular economy around it, resources will be wasted. New action is being taken to develop a fully circular product lifecycle.”