Engineer with PhD loses over B8m to scammers pretending to be from DSI

A 32-year-old expert with a PhD claimed defrauders had duped him into paying more than 8 million ringgit into their accounts.

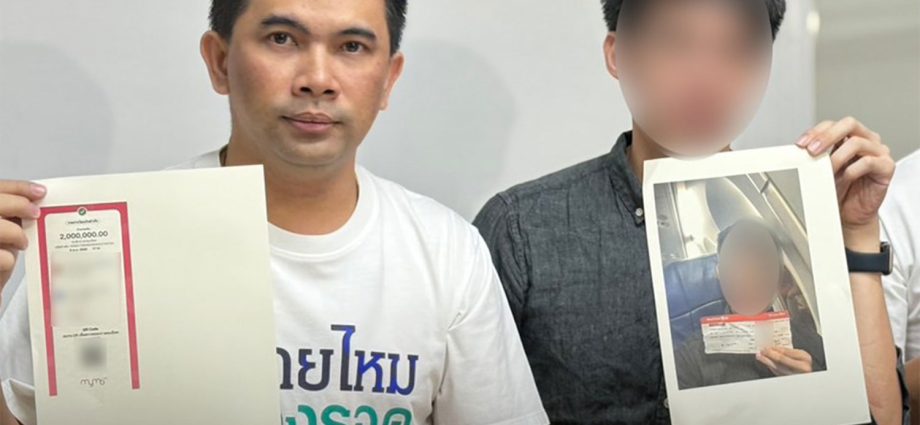

After losing a sizable sum of money to members of a call center scam gang posing as Department of Special Investigation ( DSI), the victim, who was only identified as Siwat, turned to social media activist Ekkapop Luangprasert, the creator of the Sai Mai Tong Rod ( Survive ) Facebook page for assistance.  ,

On Thursday, a popular social media platform shared his story, which quickly went viral.

Mr. Siwat, an architect, informed Mr. Ekkapop that on April 5, he received a call from a person claiming to work for the DSI. The man informed him that he was suspected of opening horse accounts for a well-known past politician who had previously been detained.  ,

Eventually, he was instructed to put the guest as a companion in the Line talk application, and the two made a video call. The visitor instructed him to move his income for “examination of the money trail” and sent him files about the sequestration of the alleged animal accounts. The visitor had mandated that the caller remain in a room or any other location without being disturbed.

Anxiety and threats

The engineer claimed that the visitor had informed him that if he did not follow the instructions, that both his and his family members ‘ property may be confiscated at the time.

Eventually, a young girl calling herself a different DSI official called him, and the call was then routed to a different person. He claimed that names were therefore made daily for seven nights and seven times. He made 11 cash payments from five bank records to the group during this time, totaling 8.46 million baht, for “examination.”

Additionally, he was instructed to travel to Songkhla province’s Hat Yai area to transfer money from a Government Savings Bank tree there. The phone remained on hold throughout Helmet Yai, aside from when he boarded a journey.  ,  ,

He didn’t realize until he told his father what had happened that he had fallen for a con crew.  ,  ,

Mr. Siwat claimed to have never been victims of this kind of fraud despite having spent nine years worldwide. He frequently received phone calls from swindlers in Thailand after returning to his job a year earlier, but he was conscious of their schemes. However, the scammers used a different method to document their schemes this day. He claimed that he felt compelled to follow their instructions because he had been frightened by their challenges.  ,

He nearly lost his property area, which is for about 7 million baht, in addition to the money he transferred. The group attempted to exchange the proceeds from the mortgage process to the owner of the condominium room, but the outcome was unsuccessful.

He claimed he had tried unsuccessfully to contact lenders to help them recover the money that had been transferred to the crew.  ,

Mr. Ekkkapop claimed to have collaborated with cybersecurity investigators to locate those linked to the hoax gang.

The social internet environmentalist demanded that the government take drastic steps to combat scams.