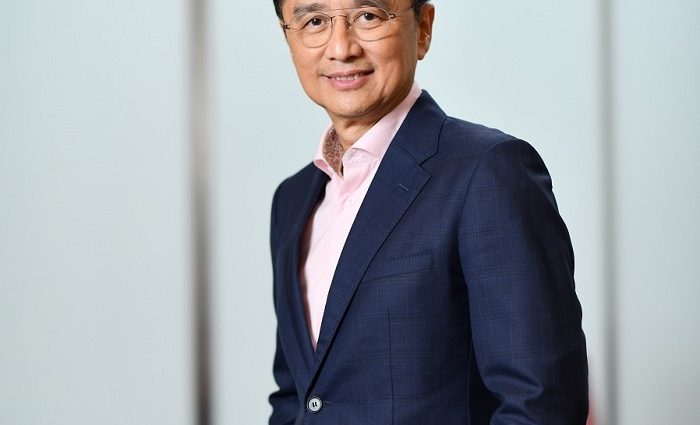

Mavcap welcomes Ter Leong Yap as its new chairman

Founder and professional president of Sunsuria Group, a real estate tycoonhas a profile worth nearly US$ 209 million that is managed directly and indirectly.Ter Leong Yap is welcomed as the new chairman of Malaysia Venture Capital Management Bhd ( MAVCAP ), effective 15 Dec 2023.Ter, who is currently the founder and…Continue Reading