Recent decades have witnessed extraordinary economic progress owing to enormous innovations in technologies. Well known is the important role of private venture capital in financing early-stage companies that grew into many of giant corporations that dominate many new industries.

Less well known is the role of the much larger private equity funds that finance the growth and modernization of established companies in many industries.

From their beginning in the early 1980s, private equity (PE) funds now manage US$7.6 trillion in assets globally, of which US funds comprise two-thirds, according to a McKinsey and Company estimate.

They had $496 million available for investment in 1983. By 2021 that number rose to $242 billion. Private equity attracts investment because in most years during the past four decades, the mean return on investment in private equity funds exceeded that of money invested in publicly traded companies.

What explains this success?

The answer is that these funds have successfully provided growth capital to many established companies while actively working with management to use this capital effectively to increase the value of the business. The emergence of new technologies and markets creates demand for capital which cannot be funded out of operating profit cash flow. That’s where PE steps in.

For the management of many private companies, PE funding is a good alternative to raising capital through an initial public offering (IPO) on the stock markets, which requires public disclosure of corporate activities, and subjects the firm to fluctuations in publicly traded share prices.

Major private equity funds that started in the 1980s were dubbed “buy-out funds” because an early strategy involved buying public companies and selling the component divisions to increase the firm’s value. Such transactions were financed by a combination of debt and private equity. But buy-out strategies now represent a minority of PE investments.

Over time, PE funds have expanded to investments in private companies aimed at providing capital to finance acquisitions, technology roll-out, marketing expansion, or improved manufacturing.

As their investment strategies broadened, PE funds expanded their staff to include experienced operating experts. In effect, the PE firms went from being a source of financing to a multi-tiered, transformational capital partner, with staffs of experts able to help portfolio companies.

In general, an acquired company will remain in a private equity portfolio for a few years during which it is expected to grow in value to allow a profitable sale to a corporate acquirer, or to the public through a stock-market listing.

The private equity industry has its share of critics. A recent example is Brendan Ballou’s book Plunder: Private Equity’s Plan to Pillage America. But Ballou’s tirades miss the point. Private equity on the whole has done so well because it has made businesses more efficient and better able to meet the needs of their customers.

A common complaint is that the transformation of portfolio companies under PE investment is sometimes unsuccessful, leaving a damaged company with substantial job losses. This sometimes happens. But transforming businesses is never easy or predictable. Poorly managed businesses fail sooner or later, and it is unlikely that the laggards would have succeeded without PE involvement.

Evidence of benefits

With many years of experience in the industry, I believe that the PE industry enhances industrial productivity through the beneficial transformation of companies that need to evolve to meet new technological or competitive situations that threaten their future. Some examples from my experience may be helpful.

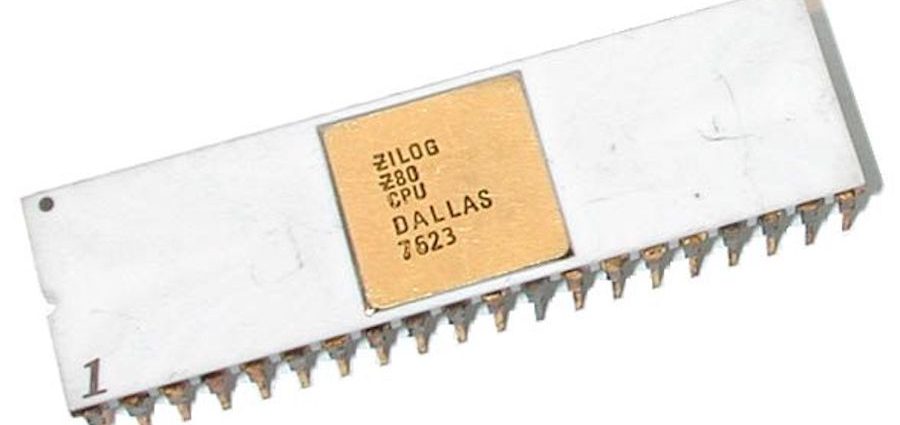

Zilog was a unit of Exxon Enterprises that designed and manufactured semiconductor chips but proved unable to grow, as it competed with large companies with obsolete products and production plant. We bought the company and, with fresh capital, its capable chief executive officer transformed the company into the world’s leading supplier of low-cost controller chips for consumer products such as appliances and TV remote controllers.

Production was modernized and marketing expanded globally. Employment grew, as did revenues and profitability. The company had an IPO on Nasdaq.

A second example of transformation is a spun-out unit of AT&T, Telcordia, that had developed much of the software used to operate American telephony. We acquired the company in partnership with another private equity firm.

The business had to be transformed from its roots in the old AT&T monopoly into a free-standing, competitive, and profitable business. This transformation took some years and involved some acquisitions, staff reductions in unproductive areas, and management changes. The company was eventually acquired by Ericsson, one of the three leading suppliers of telecommunications technology in the world.

A third example involves the leading information-technology service company in Israel. Working with a local investment banker, Raviv Zoller, we became aware that while Israel was emerging as a leading venue for IT development, it lacked a company scaled up to exploit that capability globally. We funded the acquisition of several small but excellent Israeli software companies that became the foundation of Ness Technologies.

Under the leadership of Zoller, the firm acquired several companies in Europe and India and grew to the point that Ness became the largest IT service company in Israel along with IBM. The company had an IPO on Nasdaq and was profitable.

These examples from three industries were chosen from many that illustrate what can be accomplished with focused private equity operating in open markets. In all cases, a combination of factors explained the success of the investments, but the selection of exceptional management was uppermost. All success stories start there.

Henry Kressel is a technologist, inventor, author, and long-term private equity investor at Warburg Pincus.