Singapore leaders send condolence letters to Palestinian counterparts after Gaza hospital blast

Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, President Tharman Shanmugaratnam, and Foreign Affairs Minister Vivian Balakrishnan sent letters of condolence to their Israeli rivals on Wednesday, October 18, following an explosion at a clinic in Gaza. The Al-Ahli al Arabi Hospital explosion on Tuesday, which was the bloodiest one incident inContinue Reading

FDA: No signs of deadly children’s syrup here

Indonesian court situation highlights contaminants that resulted in more than 200 fatalities.

18 October 2023 at 20: 18 PUBLISHED

According to the Food and Drug Administration( FDA ), unlike in Indonesia, the country’s syrup medications for children have not been found to contain any deadly contamination.

According to Dr. Narong Aphikulvanich, acting FDA secretary-general, the agency has not discovered any contamination with toxic diethylene glycol ( DEG ) or ethylene glucose( EG ), in medications sold in the nation.

He was speaking in response on Wednesday to a court case that is still pending in Indonesia against the producers of toxin-tainted cough sugar drugs that killed more than 200 kids the previous month.

According to Dr. Narong, the cases in Indonesia were caused by the deliberate use of the toxins to taint the propylene glycol used by pharmaceutical companies in India and Indonesia to make sugar medications.

He added that the FDA did no locate any locally produced goods made by Afi Farma, the Indian pharmaceutical company named in the legal actions.

The FDA has examined children’s sugar drugs imported from India and Indonesia over the past year, and it has not detected any contamination with DEG or EG. According to Dr. Narong, the picking and evaluation would go on for the sake of public safety.

Korat fossil came from âancient alligatorâ

In contrast to species found in the US and China, Nakhon Ratchasima has recently undiscovered types.

18 October 2023 at 20:03 PUBLISHED

According to the Department of Mineral Resources, an eel coal discovered in Nakhon Ratchasima in 2005 has been identified as being of a different species than those found in the United States and China.

A native of the Non Sung area discovered the fossilized bones, which are made up of a skull, two incisors, and five other fragments. He alerted the department.

Under two meters of shallow sediment, the legs were discovered.

The bones, which have been carbon-dated to roughly 230, 000 years ago — commonly referred to as the Pleistocene period — were then identified by the department with the assistance of a group of German researchers. & nbsp,

The bones were compared by the experts to known specimens of Alligator jasmine, which are widespread in China, and endemic to the United States.

They came to the conclusion that the eel from which the bones originated was probably a different local types.

The team’s findings were recently published in Scientific Reports, a peer-reviewed blog associated with Nature, according to Thitiphan Chuchanchot, assistant commander of the Department of Mineral Resources.

According to Mr. Thitiphan, the bones were discovered in the Mun River valley, so we gave the animal the name Alligator munensis, a guide to the location of its initial discovery.

Alligators are currently only found in the United States and China, where they run the risk of going extinct, according to Kantapon Suraprasit, a researcher with the Centre of Excellence for the Morphology of Earth Surface and Advanced Geohazards in Southeast Asia( MESA CE ).

It is unknown how the two types diverged from their shared father, but some experts think they must have both descended from the same species, an old alligator species that again roamed the Yangtze and Mekong-Chao Phraya river basins.

Hong Kong sticks a fork in disposable plastic products

HONG KONG: Is there a diner in Hong Kong that will accept plastic forks? Travel on Earth Day, nbsp; According to a bill that the city’s legislature passed on Wednesday( Oct 18 ), customers will need to start looking for more environmentally friendly cutlery starting on April 22. The fundContinue Reading

Two veteran Bangkok Post photographers pass away

18 October 2023 at 19: 19 PUBLISHED

The Bangkok Post has experienced a terrible week as two seasoned general photographers passed away due to disease.

Kamthorn Sermkasemsin, 86, passed away on Sunday after battling a protracted condition in the hospital.

Jarin Trakullertsathien, another 86-year-old fellow, passed away early on Tuesday. At the time, he was moreover receiving medical care in a hospital.

Both were seasoned photography who worked for the Bangkok Post when it had its headquarters on Ratchadamnoen Avenue. In contrast to today’s online and suddenly accessible photographs, it was a time when rolls of film had to be created.

Both joined the Post as photographers on October 1, 1964, as luck would have it, and it seems as though their profession were intertwined.

In 1968, Kamthorn was appointed Chief Photographer. Jarin was given more duty when he was elevated to Assistant Picture Editor in 1983, which also included promotion to photo editor.

Kamthorn was appointed Chief News Editor in 1986, but after 24 years of employment with the Post, he left in 1988. Jarin was appointed Chief Photographer in 1988 as a result of Kamthorn’s surrender, and he held that position until his retreat in 1997. He spent 33 years working at the Post.

Both gentlemen had different leadership styles, according to Sayant Pornnantharat, a previous Chief Photographer at the Post who worked for both of them.

Kamthorn was an expert at organizing and had a good sense of what kind of images would best capture an event or history. Before they left on an assignment, he had simple photographers.

They were sent out to take the photo once if they didn’t get what was assigned, according to Mr. Sayant.

He claimed Jarin was a more subdued leader who was honest, trustworthy, and committed to the team’s job.

Up until Friday, Kamthorn’s worship ceremonies may be held at Wat Thepsirin, Sala 4. On Saturday at 2 p.m., there will be a death meeting. In accordance with his desires, Jarin has donated his brain to Siriraj Hospital.

The Bangkok Post news, specifically its photography, will regrettably miss both people.

Activists demand âtruthâ about Thaksin hospital stay

Group threatens to go to Police General Hospital’s 14th surface for a first-hand examination.

Published on October 18, 2023, at 18:43

Thaksin Shinawatra, a former prime minister who is currently imprisoned, has been urged by the Ministry of Justice to halt bestowing special privileges on him. The organization is known as the Network of Students and People Reforming Thailand.

The team has threatened to visit Thaksin’s alleged lodging in the Premium Ward on the 14th surface of the Police General Hospital to determine whether he is actually there and ill enough to warrant being treated there if the government does not comply with its demands.

Days after returning from 15 years of self-imposed captivity on August 22, Thaksin was taken to the hospital from Bangkok Remand Prison. Prior to 2006, while serving as top, he was given an eight-year jail term that was later reduced to one time by a royal pardon for abuse of power and conflict of interest.

According to group representative Pichit Chaimongkol, the group’s three-point demand is that Thaksin be sent back to prison right away, that his treatment be continued outside of prison, and that a human rights organization be permitted to keep an eye on his health and spread the” truth” to the public.

He claimed that the department had been unable to persuade the populace of Thaksin’s true illness.

Last month, a picture of Thaksin being taken for an MRI test went viral on social media. Officials claimed that he was immediately taken back to his room. Officials from the Department of Corrections and medical staff at the hospital have declined to discuss the prisoner’s condition, citing calm confidentiality.

Thaksin, 74, is renowned for having high blood pressure, heart and respiratory issues, and another aging-related illnesses. According to his daughter Paetongtarn, he underwent surgery last quarter for an unidentified state.

The requirements of the protesters are directed at Phongsaward Neelayodhin, the everlasting minister of justice, who will soon have to determine whether Thaksin can continue to receive care outside of a prison hospital.

Any be longer than 30 days may be approved by the director general of the Department of Corrections based on a medical mind under the rules governing criminal payments to outdoor facilities. The decision was made on September 22.

The permanent secretary for Justice must approve the treatment if it lasts longer than 60 days, or after Oct. 22 in Thaksin’s event. If a course of treatment lasts longer than 120 time, the justice minister must approve it.

Another group representative, Nazer Yihma, stated that the ministry would be forced to ascend to the hospital’s 14th floor to determine whether Thaksin was actually poorly or not if it did not answer its call.

The team will then appeal the National Anti-Corruption Commission to look into Ms. Phongsaward for dereliction of duty if she doesn’t answer the call, he continued.

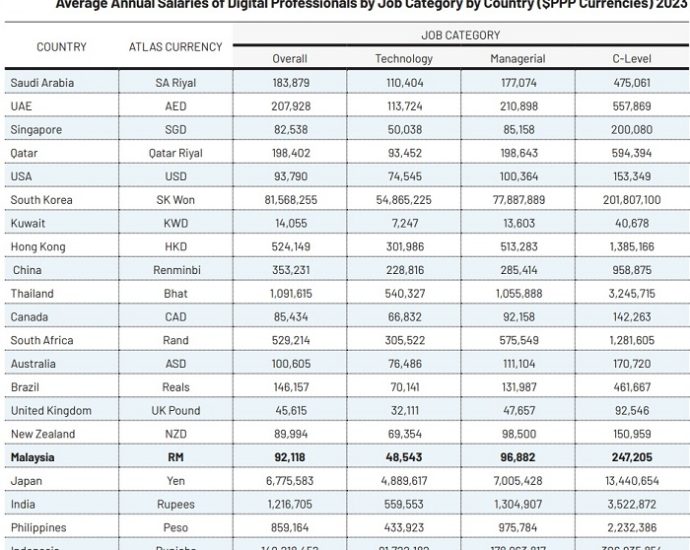

IT salaries in Malaysia show largest % jump according to Pikomâs Economic and Digital Job Market Outlook 2023

25.5 % projected growth in the digital economy in 2024, surpassing the national goalPikom also experiences an annual average growth rate of 6.45 %& nbsp over a 10-year period.According to Vanessa Tan, CEO and owner of HT Consulting( Asia ) Sdn Bhd of Pikom’s( National ICT Association of Malaysia ) Economic…Continue Reading

Police seek scam gang linked to girlâs suicide

Permits are being sought for the owners of a bogus mobile phone shop that enticed teenagers to make payments in installments.

A 19-year-old student who was tricked into paying for an phone 13 that she never received is thought to have committed suicide by hanging, and authorities are preparing to file an arrest warrant for them.

According to a police investigation, the Mathayom 6 ( Grade 12 ) student had used Facebook to get in touch with the” Hannah” mobile phone shop.

However, investigations revealed that the store was false, and the website provided a false tackle for Chiang Rai’s Mae Sai area.

The woman, who resided in the southern state of Nakhon Si Thammarat, was tricked into paying for an iPhone 13 and forced to make installment payments for various expenses.

The woman ultimately paid 18,500 baht in full. The funds were sent to the ghost purchase through a bank account that was registered with the name Dokkaew Kewjerm. Since then, the bill has been frozen.

Additionally, the victim was duped into making a” guarantee” payment of an additional 2, 000 baht.

The woman sent the final payment and didn’t get a call, according to the officers, when she realized she was being duped. She tried in vain to get in touch with the seller through a Line talk class but was unsuccessful.

She was so stressed out that she feared her relatives had chastise her for borrowing money from two school associates to purchase a unit they couldn’t afford.

She expressed her frustration with the strain she was experiencing in her last talk message with her friends. Her companions suspected something was wrong and called her home when the child’s information abruptly stopped.

On Monday, the woman hanged herself at her residence in the Pak Phanang neighborhood of Nakhon Si Thammarat’s tambon Koh Thuad.

According to Pol Lt Gen Worawat Watnakhonbancha, the CCIB chief, Koh Thuad police transferred the case to the Cyber Crime Investigation Bureau( CCIB ) on Tuesday after the victim’s parents complained online.

According to Pol Lt. Gen. Worawat, CCIB Division 5 officials are tracking the girl’s transfers to the seller as well as the Facebook website and Internet handle of the fake store.

Within two weeks, the offenders should be apprehended, according to the authorities. To challenge arrest warrants, information has already been gathered.

The Division 5 captain, Pol Maj Gen Charin Kopatta, claimed that the mob had four pony bank accounts, one in Chaiyaphum and the others in Chiang Rai.

According to police, the woman’s cash transfers were sent to a bank in the border city of Tachileik in Myanmar from Chiang Rai.

When Ms. Dokkaew, the owner of the horse account that received the girl’s bills, was questioned by authorities in Chaiyaphum, she denied having any connections to the band.

She asserted that she was unaware that the bill had been opened using her personal information, including her citizenship ID cards.

The 27-year-old user of the phone company” Family” in Nakhon Sawan complained to the local authorities on Wednesday after discovering the con artists had used the store’s symbol on their website.

Civilization and its enemies: a letter to a Chinese friend

I had the privilege of writing the entry for Professor Wen Yang’s book The Logical of Chinese Civilization next year. China Daily published an abridged version of & nbsp. How has Foreign society survived for 5,000 years while all other societies in Western Asia and Europe vanished? & nbsp,

Professor Wen contends that while the West also reflects the traits of its hunter-gatherer grandparents, China developed a sedentary lifestyle thousands of years ago. & nbsp,

I noticed that China” assimilated individuals representing six main and 300 small language groups.” China united its diverse peoples through a common method of characters and downstream infrastructure, while native spoken languages, religion, and culture flourished. This is in contrast to Europe, which required its people to convert to Christianity in order to enter Western civilization. & nbsp,

But absorption occasionally failed. The Han dynasty was in danger from the wandering Xiongnu in the third century BCE. In order to deal with north nomad, the Han Dynasty tried a variety of strategies, including paying tribute to the warriors and marrying Chinese ladies to Xiongnu monarchs and encouraging the adoption of Taiwanese culture. These strategies included offensive and defensive wars. & nbsp,

The Han Dynasty was unfortunately forced to battle the Xiongnu. General Wei Qing’s troops did not overcome a sizable Xiongnu power until 124 BCE. The risk of the barbarians persisted. The Mongol and Manchu warriors conquered all of China more than a thousand years after.

Chinese culture was so resilient that it eventually assimilated the savage invaders, though not without great suffering and loss. All of the major systems used in the Industrial Revolution in Europe were created by the Tang and Song empires. Why did China never experience the Industrial Revolution, researchers wonder. The solution may be that barbarian invaders disrupted China to the point where its advances were unable to develop.

The threat of barbarians still exists despite China’s spectacular military prowess and unmatched economic growth. I’ve heard Chinese scholars claim that the United States purposefully incubated jihadists to destroy China during numerous trips to China over the past ten years. Although I don’t think the US intentionally did this, China undoubtedly suffered as a result of British mistakes in the so-called Global War on Terror. & nbsp,

In order to have the Sunni uprising against the American-sponsored Shi’ite majority government in Iraq, the Bush administration gave General David Petraeus a blank check in 2008. Past Sunni military officers received salaries from Petraeus totaling US$ 16 million per month.

The foundation of ISIS was afterwards formed by a large number of Sunni soldiers who were funded and armed by the US. According to an a & nbsp report released by the Defense Intelligence Agency in 2012, America’s support for Sunni jihadists in Syria encouraged the rise of ISIS.

Uighurs fighting in Syria take aim at China, according to a report by The & nbsp on the Associated Press in 2017. According to the AP statement:

Since 2013, dozens of Uighurs, a Muslim majority from northern China who speak Turkic, have traveled to Syria to station with the Turkistan Islamic Party and fight alongside al-Qaida, taking important part in numerous wars. As the six-year issue comes to an end, Syrian President Bashar Assad’s forces are currently engaged in combat with Uighur combatants.

However, China’s worst worries might start with the end of the war in Syria.

Ali, who would only give his first name out of concern for retaliation against his family back home, said,” We didn’t worry how the battle went or who Assad was.” We only intended to return to China after learning how to use the arms.

The same anti-civilizational warfare that taught jihadists to kill Chinese includes Hamas.

During trips to China, I had the opportunity to hear the opinions of eminent Chinese scholars and military managers as a panel member of an Israeli foundation that was involved with Israel-China relationships. A persistent worry has been the possibility of warfare spreading to Southeast Asia. The Chinese scientists emphasized that China has close ties to numerous Arab nations and a Muslim community that supports the cause of the Palestinians. & nbsp,

I don’t intend to give China advice on how to do diplomacy because China has its own grounds for remaining impartial on Israeli-Palestinian problems. Nevertheless, some aspects of the issue might not be fully understood.

Israel’s treatment of Hamas over the past few years has been modeled after the Han dynasty in its original attempts to appease the Xiongnu. Israel urged Qatar to give Hamas$ 40 million per month in incentives. According to reports, the mind of Mossad visited Qatar in 2020 to advocate for such grants. Israel opened the Gaza borders to 20,000 Arabs working in Israel over the course of the previous year in an effort to improve financial problems. & nbsp,

The Netanyahu government believed it had all strategic bases covered and that it could bribe Hamas to remain on the sidelines as it negotiated diplomatic relations with Saudi Arabia, as I stated in an & nbsp, October 11 essay & ndrp for the American website Law & amp, Liberty. It lulled itself into a careless cloud that obscured the ancient world’s recalcitrant elements that opposed the Abraham Accords’ modernizing impulse.

That is where the” knowledge loss” began, allowing tens of thousands of Hamas jihadists to invade Israel and kill more than 1,300 people, including hundreds of children and teens. Israel’s tragedy reports are not a tool of American propaganda. The majority of them are known to us thanks to video posted online by Hamas, which aims to frighten both Israelis and the rest of the world.

According to Professor Wen’s theory, Hamas is a holdover from the pre-civilizational, wandering earth that won’t accept assimilation. A two-state option is not what Hamas wants. According to its contract, Israel must be destroyed and an Islamic state should be established in its place. This is not a typical cultural issue that can be resolved by dividing the issue in half. & nbsp,

According to Hamas’ Charter,” The Islamic Resistance Movement is a recognized Palestinian movement, whose loyalty is to Allah, and which practices Islam.” Israel will be and may continue to exist until Islam destroys it, just as it destroyed another before it ,” it adds, attempting to raise the banner of Allah over every square inch of Palestine.

According to remark in guancha.cn, per capita income in the West Bank, where Israel continues to be the supreme power, is twice that of Gaza, which Hamas annexed in 2007 after Israel withdrew from the region on its own. Its arbitrary massacre of defenseless civilians, including children, is eerily similar to ISIS ‘ tactics.

No state has the right to survive if it allows a neighbor to off thousands of its citizens. Israel has no other option but to exterminate Hamas. In order to win sympathy from the rest of the world, Hamas tries to increase the number of casualties among its own civilizational people, as I explained in the remark for guancha.cn that was cited. Hamas asserts that it is battling Zionist” occupation.” nbsp

In actuality, Israel gave the Palestine Authority control of Gaza after formally ending its occupation in 2005. In 2007, Hamas deposed the Palestine Authority administration. More than 20,000 rockets have been fired at Israeli civilian goals since then by islamist terrorists. These were a lot of rudimentary products. & nbsp,

Some returned to the densely populated Gaza Strip, as I noted in my opinion from 2022, and killed a lot more Arabs than Israelis. One of many instances of criminal rockets killing Gazans more than Israelis was the loss of a hospital in Gaza on October 17.

Because Hamas uses Gazan civilians as human shields, Israeli actions in self defense will eventually result in human deaths. This will stoke Arab sentiment throughout much of the earth. The optimistic public stance of China is not unexpected. However, China should carefully consider where its interests in the Gaza fight lie.

China is worried about the free flow of oil from the Persian Gulf, which supplied 54 % of China’s oil imports in 2022, in the short term. With imports to Saudi Arabia almost tripling between 2018 and 2023, China’s business success in the Persian Gulf has matched its political accomplishments. Iran is the primary supplier of arms to Hamas and aids in the ongoing issue. China may undoubtedly advise Iran to prevent increase.

However, China’s involvement in the fight goes beyond just power security. China’s export to the Global South, which have doubled since 2019 and now outnumber those to developed industry, have a significant impact on its financial future. & nbsp,

China is bringing digital and physical infrastructure to billions of people who are currently at the periphery of the global economy, integrating them quickly into global markets, as I stated in my 2020 book: & nbsp, You Will Be Assimilated: China’s Plan to Sino-Form the World and in many subsequent articles. & nbsp,

China exports investment and technology to support the attempts of young people in the Global South as its local labour force shrinks. China wants to double its infrastructure-driven development model around the world, which is both an economical and a hegemonic essential.

China is a global modernizing army. China’s reputation in the Global South, where the general public has a favorable view of China, has improved thanks to the Belt and Road Initiative. However, this will not take place without criticism. Anti-modern tendencies from pre-civilizational parts in society still exist and represent the biggest barrier to China’s aspirations. & nbsp,

Numerous Chinese citizens have been killed in terrorist attacks by Hamas-like jihadists in Pakistan, and according to press reports and nbsp, security concerns are impeding Chinese investment in the$ 65 billion nation. & nbsp,

Anti-civilizational aspects around the world will take center and look for new target if Hamas survives the current conflict with Israel. Israel is currently at the center of society. The underlying interest of China is for the warriors to be driven out of Gaza.

The path of least resistance suggests a global split along professional – and anti-American lines. Israel became an American friend following the 1967 War as a result of Cold War planning. & nbsp,

But, it is not a creature of the United States. Israel made a concerted effort to stay out of the Ukraine War and keep cordial ties with both Russia and China. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared he may travel to China in June. & nbsp,

America is forced to support an alliance that has been brutally attacked in the current crisis, and its critics are aligning themselves against it. That will only result in more conflict and subsequent issue escalation. & nbsp,

For the time being, Iran is unlikely to get involved, but it will make an effort to gird Israel in the future. Israel is prepared to use its numerous atomic weapons if its survival is in jeopardy. Although I don’t think a world war is imminent, the escalation of tensions between Israel and the rest of the world could result in an impending disaster.

China may hope that Israel is successful in eradicating the barbarians who pose a short-term threat to Israel’s existence and, over the long term, to civilization itself if it wants stability in the area and the development of civilization. & nbsp,

David P. Goldman, a deputy editor for Asia Times, serves on the SIGNAL ( Sino-Israel Government Network and Academic Leadership ) Advisory Board.

This article’s opinions are his own and do not always reflect those of any organizations to which he is affiliated.

South China Sea a ticking time bomb waiting to explode

In the midst of yet another round of hostilities in the South China Sea, Vice Admiral Alberto Carlos, the head of Western Command of the Armed Forces of The Philippines( AFP ), stated that” these[ dangerous ] maneuvers pose significant risks to maritime safety, collision prevention, and danger to human lives at sea.”

The major Asian military official stated that China must stop these risky actions right away and conduct itself professionally by abiding by international law after it was claimed that a Chinese navy ship had attempted to cross the path of another ship in the disputed Spratly island chain close to Thitu Island.

According to Philippine authorities, the incident happened on October 13 as a People’s Liberation Army-Navy ( PLAN ) ship known as Ship 621 and the Philippine Navy( PN ) BRP Benguet were engaged in combat. According to reports, the Taiwanese ship attempted to avoid a resupply mission by crossing the Spanish ship’s bow at close range of 320 meters.

The Philippines has maintained control over the strategically located Thitu Island since the 1970s by constructing military facilities and completely establishing a human community, including occasionally residing mayors, on the disputed feature.

General Romeo Brawner, the chief of staff of the Philippine Armed Forces, quickly responded to the most recent sea tensions by cautioning China against” dangerous tactics and violent actions towards Asian arteries ,” which he claimed was endanger” the life of coastal personnel from both sides.”

The Philippines and China have been embroiled in a months-long political and maritime conflict in the South China Sea, making it far from an isolated event. & nbsp, Manila is taking a little firmer approach to the problems, signaling to China the new political reality in the contested waters, and is now enjoying growing support from friends and like-minded powers, including agreement friend the US.

The Second Thomas Shoal, the Reed Bank, and recently improved US access to Spanish bases near Taiwan are just a few of the issues that are escalating diplomatic tensions, which are also causing the Philippines to experience multiple” ticking explosives.” It’s unclear how far the Philippines can go without eliciting a hostile Chinese answer.

Before the wind, quiet

China had a very advantageous position in the South China Sea up until recently. Rodrigo Duterte, a former president of the Philippines, not just threatened to destroy his nation’s defense ties with the West, but he also cautioned against asserting Asian sovereign rights in the contentious waterways.

The Philippines’ traditional mediation award victory at an judicial tribunal in The Hague, which rejected China’s extensive claims in the South China Sea, was the first thing Duterte decided to” set off.” The then-Pakistani president made dubious claims on numerous occasions, claiming that if the Philippines pursued its lawful claims, it may harm going to war with China.

Following one of his meetings with the Chinese leader, Duterte declared,”[ Xi’s ] response to me was ][ we’re friends, we don’t want to quarrel with you, but we wanted to maintain the presence of warm relationship. However, if you force the issue ,” we’ll go to war. Beijing not endorsed or refuted Duterte’s claims as being true.

Following this, the Filipino leader adopted a profoundly fatalistic stance, cautioning that” standing up to China, including over the Thitu Island, is tantamount to” preparing ] for suicide missions.” Duterte contradicted his own defense authorities by dismissing the incident as a” little maritime accident” when it occurred, which involved the ramming into and subsequent sinking of an unknown Chinese military vehicle.

When Ferdinand Marcos Jr., who topped most pre-election studies conducted prior to last year’s election, emerged as Duterte ‘ most likely son, China was upbeat about the progression of the then-subservient foreign policy of Manila. After all, Marcos Jr. frequently questioned the value of the Philippines’ bond with the US and emphasized the importance of speech with China when running for president.

However, the Marcos Jr. leadership changed course on the South China Sea just a month after taking business. This came about as a result of the revelation that Duterte’s China-friendly foreign policy had only served to weaken the nation, with China refusing to make any significant concessions despite ongoing high-level discourse for more than six years.

As a result, not only did the new president of the Philippines adopt an unyielding stance on the marine disputes, but he also favored increased defense cooperation with the US and its supporters. The Philippines has most significantly increased the scope of the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement( EDCA ) by giving the Pentagon new access to a number of strategically situated bases that face both Taiwan and the South China Sea.

However, the East Asian country likewise used intense public politics at the same time, frequently exposing China’s alleged aggressive behavior in the contentious waters.

Under the previous [ Duterte ] government, any issues involving China were only brought to public attention if they were particularly severe, but under Marcos Jr., there is a” commitment to transparency and … resolve to protect the country’s sovereignty ,” according to Jay Tarriela, spokesman for the Philippine Coast Guard.

There is now agreement among the Spanish coastal security establishment that the fight must be taken to China through vigilant diplomacy as well as increased naval and law enforcement operations. By essentially ignoring Beijing’s warnings and reducing its safety assistance with the US and its allies, Manila has thus been able to fortify its proper position.

difficult decisions

Both factors will have to make difficult decisions in the near future. The Second Thomas Shoal, where a Filipino sea insulation has been dangerously stationed over an abandoned grounded vehicle, is where the Philippines first encounters its moment of truth. The Philippines must seize control of the contentious Reed Bank, which is thought to contain sizable hydrocarbon militia, because it is running out of time to develop alternative energy sources.

While obstructing Spanish supplies expeditions to the Second Thomas Shoal, China has harassed Spanish electricity exploration efforts in the Reed Bank. If Manila construct new buildings on the disputed shoal, China has also issued a warning about direct intervention.

Manila, now outfitted with and deploying ever-more present vessels, hopes to disrupt Beijing’s invasion strategy in the contested waters by leveraging its growing defense relations with the West.

However, the Philippines’ decision to give American forces access to military facilities in the northern provinces bordering Taiwan, directly affecting any future Chinese dynamic action plans, is just as contentious. & nbsp,

The end result is a complicated” Taiwan-South China Sea link” that has increased the risk of potential Foreign retaliation while also bolstering the Philippines’ strategic location.

In the future, Manila might consider restricting American military presence near Taiwan in trade for China implicitly acknowledging the Southeast Asian country’s right to protect its position in the Second Thomas Shoal and, possibly as part of a service agreement, produce hydrocarbon resources at the Reed Bank.

For the time being, however, it is evident that both factors are testing the waters in an effort to avoid a potentially fatal armed opposition by holding and fortifying their positions. & nbsp,

Follow Richard Javad Heydarian at @ RicheyDarian on X, formerly Twitter.