How Chinaâs gallium and germanium bans will play out

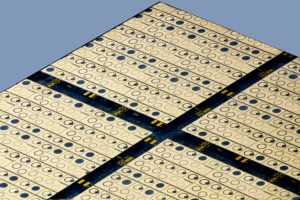

From August, China is to restrict exports of gallium and germanium, two critical elements for making semiconductor chips.

With China dominating the supply of both elements, exporters will now need special licenses to get them out of the country. The move has the potential to harm a range of Western tech manufacturers that use these elements to make their products.

The move is reportedly in response to Western restrictions on equipment vital for making semiconductor devices.

Above all, the US CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 curtailed exports of high-end microchips and technology to China, potentially affecting Beijing’s capacity for high-performance computing in areas such as defense. Other nations such as Japan and the Netherlands have also imposed restrictions.

So how important are the new Chinese restrictions and what are the implications likely to be?

Silicon is the most widely used material in semiconductors, and is very abundant. But germanium and gallium have specific properties that are hard to replicate and lend themselves to certain niche applications. These get incorporated into countless devices such as smartphones, laptops, solar panels and medical equipment, as well as defense applications.

Both elements are also crucial to technological advancement over the next few years. Germanium is particularly useful in space technologies such as solar cells because it is more resistant to cosmic radiation than silicon.

With the physical limits of silicon being approached in some technologies, increased use of germanium is mooted as a way of overcoming these limits. It is already used in small quantities in some semiconductors to improve things like electron flow and thermal conductivity.

As for gallium, 95% of it is used in a material called gallium arsenide, which is used in semiconductors with higher performance and lower power-consumption applications than silicon. These are used in things like blue and violet LEDs and microwave devices.

Meanwhile, gallium nitride is used in semiconductors in components for things like electric vehicles, sensors, high-end radio communications, LEDs and Blu-Ray players. Its use is expected to grow significantly.

Both gallium and germanium are on the European Union and US lists of critical elements. The UK considers gallium to be critical to its manufacturing interests, though sees germanium as less important.

China controls about 60% of all germanium supplies. The element is derived in two main ways, as a by-product of zinc production and from coal. These respectively account for about 75% and 25% of the total supply.

China dominates germanium that comes from zinc production. The US is one of the alternative suppliers, with deposits in Alaska and Tennessee and additional refining capacity in Canada. But as it stands, the US is still over 50% reliant on imported germanium.

Germanium from coal has several drawbacks. Two of the main producers are Russia and Ukraine, and the war has affected supplies to the west from both countries. In the years 2017-20, Russia was supplying 9% of the US germanium requirement, for instance, but this is now likely to have stopped.

In response to the Chinese restrictions, Russia plans to increase germanium production for its domestic market. This may at least alleviate global demand, even if it won’t help the West directly.

Germanium from coal is also at the mercy of the power industry, since certain coals rich in the element are burned as an energy source. In addition, germanium from coal will become more difficult as much of the world seeks to phase out coal power, which again could tighten supplies.

With gallium, China accounts for around 80% of the world supply, deriving it mainly from aluminum production. There’s actually no shortage of gallium, but even before the new controls, the supply was restricted by a lack of production capacity.

Gallium is also obtained by recycling semiconductor wafers, which are thin slices of semiconductor used in electronic circuits. But once the circuits are integrated into products, the quantities of gallium in each one are so small that it becomes challenging to recycle.

A Nature Communications paper in 2022 noted that gallium is “almost never functionally recycled” once it reaches final products.

The full impact of China’s new export regime depends on a number of factors, including the severity of the controls in practice, and the response of Western governments and companies. As it stands, the controls look likely to lead to higher prices for gallium and germanium, as well as longer delivery times.

This could make it more expensive and difficult for Western companies to produce electronic devices, which could in turn lead to higher prices for consumers. It could also make it more difficult for Western companies to compete with Chinese companies.

In an echo of how the global microchip shortage during the Covid pandemic considerably affected tech manufacturing, this points to a significant impact on the global economy.

The long-term effects of the controls are difficult to predict because so many factors are involved. Stockpiles of the elements should help to some extent: the US has said it holds inventory of germanium, though not gallium.

Western manufacturers may be forced to diversify their supply chains by obtaining components containing the elements from countries to which China is willing to export. This could lead to increased costs and complexity.

Another avenue is to increase production from alternative sources. In the past, germanium has been derived from minerals mined in Germany, Latin America and Africa, so these options may come back on the table. There is also the potential to invest in researching devices that are less reliant on these critical materials, but that would take time to bear fruit.

Clearly, the move is a significant escalation in the tech war between China and the West. The concern is that it could go further: China dominates the supply of a whole range of vital materials known as rare earth metals, as well as other materials which are required for the clean energy transition. Even before the escalation in hostilities over the past couple of years, China had used its dominance over certain materials as leverage in trade disputes.

So this latest development is concerning to say the least. At a time when the international challenges faced by humanity are greater than ever, the emergence of a new resource nationalism is the last thing anyone needed.

Gavin D J Harper, Research Fellow, Birmingham Centre for Strategic Elements & Critical Materials, University of Birmingham

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Singapore’s cultures can grow stronger by evolving, learning from each other: Tharman

SINGAPORE: “Xiang hu jing zhong”. As he uttered these words, which mean “respect for all”, former Senior Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam received cheers and applause on Sunday (Jul 9) at his first public event since he left his government posts. Clad in a signature batik shirt alongside his wife who donnedContinue Reading

Japan sea sludge tells story of human impact on Earth

That perfect preservation is the result of several unique characteristics, explained Yusuke Yokoyama, a professor at the University of Tokyo’s Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute, who has analysed core samples from the site. The bay floor dips down quickly from the shoreline, creating a basin that traps material in theContinue Reading

Is there an opportunity for Malaysia in carbon capture?

46 trillion cubic feet of potential carbon storage capacity identified

Tax incentives were announced in Budget 2023 to spur activity

Malaysia has pledged to cut carbon intensity against GDP by 45% by 2030 compared to 2005 levels, in line with its commitment to achieving carbon neutrality by 2050. As previously reported by…Continue Reading

One dead as Japan warns of ‘heaviest rain ever’ in southwest

TOKYO: One person is dead and three missing in landslides in southwestern Japan, authorities said on Monday (Jul 10), as the country’s weather agency warned of the “heaviest rain ever” in the region. A 77-year-old woman was confirmed dead in a landslide that entered her home overnight in rural Fukuoka,Continue Reading

The rush for nickel: ‘They are destroying our future’

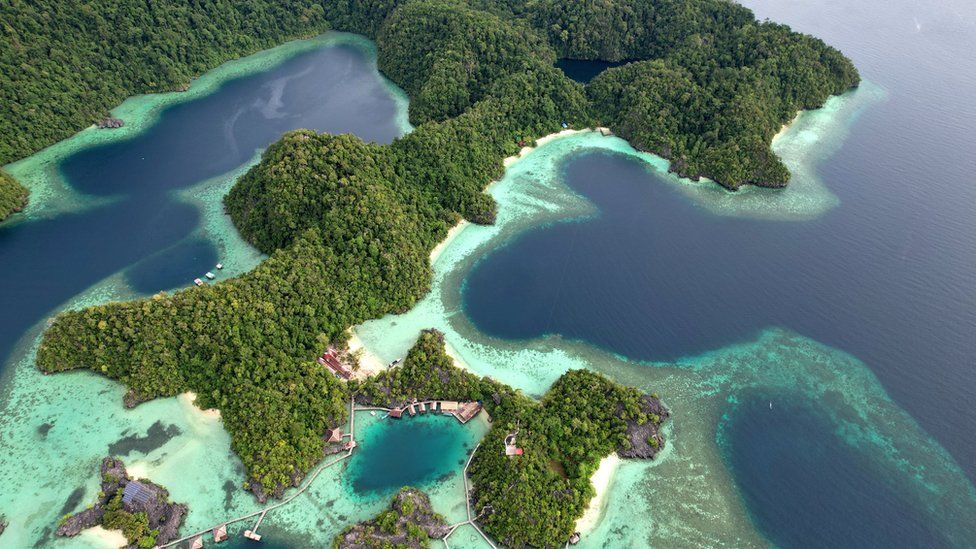

Two men are carrying torches and homemade arrows as they slip into the ocean at night on an Indonesian island.

They are from an indigenous community of Bajau people – renowned freedivers who find it better to hunt in the dark when fish, lobsters and sea cucumbers are less active.

But they fear time is running out for their traditional way of life.

“Right now, the water is still clear,” says Tawing, one of the fishermen. “But it won’t stay that way… nickel waste enters our water during the rainy season and the current carries it here.”

Nickel is an integral part of global life, used in stainless steel, mobile phones and electric car batteries. As the world shifts to greener vehicles and needs more rechargeable batteries, the International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts that demand for nickel will grow by at least 65% by 2030.

The IEA expects Indonesia, the world’s largest nickel producer, to meet two thirds of the world’s needs for the metal. The country has already signed deals worth billions of dollars with international players keen to invest in processing plants as well as mines.

But conservationists warn that mining could have a devastating effect on the environment.

Here on Labengki Island in Southeast Sulawesi, Tawing fears that if the government does not take action, waste from nickel mines will end up in the sea, damaging the island and surrounding marine life.

According to data from the Indonesian government, about 50 nickel mining companies currently operate in North Konawe Regency, across the water from Labengki Island.

The journey to get there takes us about an hour by boat. As we approach, the green hills are replaced by brown, deforested patches. Excavators and barges can be seen digging and carrying the “new gold”. The water beneath us is a reddish-brown colour.

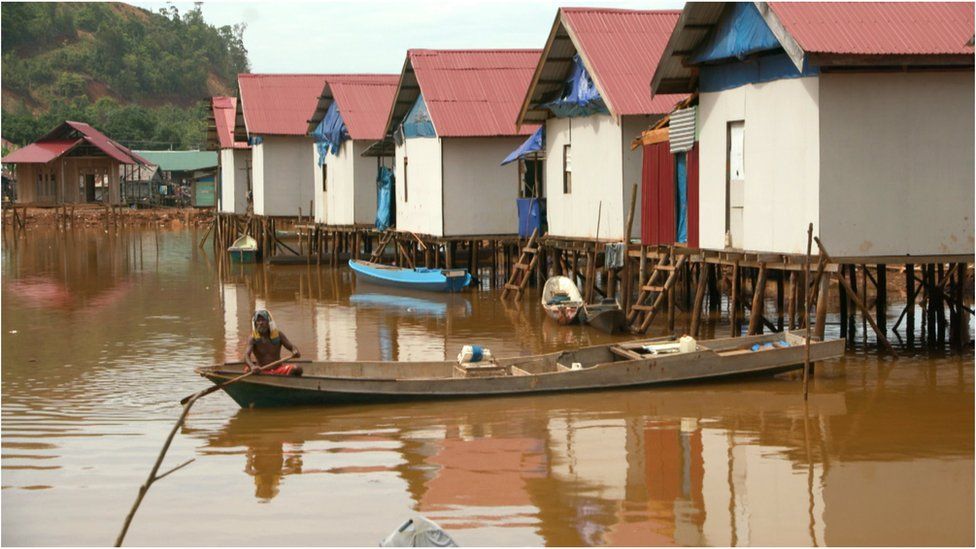

In the coastal village of Boenaga we meet Lukman, another Bajau fisherman, who says he can no longer fish near his home.

“We couldn’t see anything underwater when we dived,” he says, pointing at brown water at the back of his house. “We could hit a rock.” The cost of fuel makes it impractical for him to travel further afield to fish and he says if they make a fuss the police end up getting involved.

In order to mine nickel, large areas of trees are cut down and the land is excavated to create open pits. With the roots of the trees no longer present to stabilise the ground, when it rains earth is more easily swept away.

Government data shows that in 2022 there were at least 21 floods and mudslides in Southeast Sulawesi. Between 2005 and 2008, before the proliferation of mines, there were two to three per year, according to the National Agency for Disaster Countermeasure.

Chemicals such as sodium cyanide and diesel can be also used in the mining process. That worries local conservationist Habib Nadjar Buduha, who says that when waste material and water are not properly managed, sediment ends up in the sea.

He showed me a video he shot about 10 miles along the coast, off Bahubulu Island, of a coral reef “suffocated” by sediment.

He is afraid that the same thing will happen in Labengki and in 2009 he founded a conservation group to protect giant clams. “They would never win against nickel pollution,” he says.

“The sediment will bury and destroy them.”

Individual nickel mining companies near Boenaga did not to respond to our requests for comment, but we did speak to the Indonesian Nickel Miners’ Association – about half of the mining companies in North Konawe are members.

The secretary general, Meidy Katrin, says that in order to get a licence companies must agree to carry out reforestation or reclamation of the land when they have finished mining an area.

“The question is, are the companies doing it?” she says, admitting there are patches of bare land that have not been reforested. But she says this may not be the fault of companies with permits: “This area also has a lot of illegal mining activities.”

She puts the onus on the government to check up on miners to make sure they are complying with the rules and ensure that what they put in their reports matches the reality.

The head of Boenaga village, Jufri Asri, sees things differently to Lukman and Habib. He believes the mines have brought benefits to his community. “Take the price of fish,” he says. “I don’t take fish to the city to sell because the price is higher here. These companies need fish too.”

His 21-year-old son has a job at a nearby nickel mining company and, like other families in Boenaga, they receive a monthly compensation fee of at least $70 a month from the mines.

Financial agreements are common and are designed to offset any inconvenience caused by mining activity and heavy vehicles travelling past homes as they go to and from the pits. Jufri notes that if nickel production increases, the amount of compensation they get also goes up.

In the capital, Jakarta, we meet Novita Indri, a campaigner for Trend Asia, an NGO that promotes sustainable development. She blames the authorities for being “too weak” – she wants to see higher environmental standards and tougher regulation.

“We don’t have a track record of sustainable mining yet,” Indri says. “Indonesia has a lot of homework to do, strengthening law enforcement, increasing emission standards, and implementing environmental regulations.”

When we put this to the adviser to the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (ESDM), Professor Irwandy Arif, he tells us the government is concerned “about the impact of mining activities on coastal sedimentation”, not just in this region but across Indonesia.

However he believes pollution is caused by illegal nickel mines, not licensed companies.

He insists regulations mean that legitimate operators have water management systems in place to ensure nothing dangerous ends up in the sea and he does not believe they would ignore the rules and risk losing their permits.

But Prof Arif acknowledges that at illegal mines without treatment systems “the soil will just be eroded”.

He tells us that anyone who doesn’t comply with the regulations is prevented from selling nickel and that two illegal miners have been taken to court in the North Konawe Regency – the area where Boenaga is located.

But Prof Arif admits supervision needs to improve: “Illegal mining exists everywhere in Indonesia,” he says. “So far we have not managed to regulate it properly… we need to map which ones are legal and which ones are illegal so that we can minimise this environmental damage.”

He points out that in order to try to improve the situation, the government recently established a national illegal mining taskforce.

But many of the Bajau people we spoke to say change is not happening quickly enough. If things continue as they are, conservationist Habib warns that the damage could be irreversible.

“What they are destroying is our future,” he says.

Related Topics

Byju’s: The unravelling of India’s most valued start-up

Getty Images

Getty ImagesByju’s, once among the most valued edtech start-ups in the world and a darling of investors during the Covid-19 pandemic, has seen a dramatic downturn in its fortunes after operational and financial setbacks in recent months. Experts say it marks a necessary correction in the bull run of Indian start-ups.

“Byju’s is a company that has grown too fast too soon,” says Shriram Subramanian, who heads an independent corporate governance research and advisory firm.

Founded in 2011, Byju’s launched its learning app in 2015. With 15 million subscribers by 2018, the edtech firm became a unicorn (valued at $1bn) amid much fanfare.

It expanded substantially during the Covid-19 pandemic as students turned to online classes during lockdowns. But in 2021, it posted a loss of $327m, which was 17 times more than the previous year.

Since then, the edtech giant has witnessed an extraordinary unravelling. Valued at $22bn (£17.28bn) last year, Byju’s has seen its valuation slashed to $5.1bn this year by Prosus NV, the company’s biggest investor and shareholder.

The company did not respond to the BBC’s queries.

“After the pandemic, when children returned to schools there was going to be a downturn,” Mr Subramanian said. “But Byju’s kept on growing and investors kept on putting money into it. They did not see the signs that there could be a downturn.”

Aniruddha Malpani, an angel investor and vocal critic of Byju’s business model, says the company had “paper fortunes”.

“There’s a big gap between value and valuation,” he said.

With exponential growth during the pandemic, Byju’s went on an acquisition spree in 2021, spending $2bn to acquire edtech start-ups and firms like WhiteHat Jr, Aakash, Toppr, Epic, and Great Learning.

It soon surpassed digital payments platform Paytm to become India’s most-valued start-up.

Byju’s channelled hundreds of millions into its marketing, roping in Bollywood superstar Shah Rukh Khan and football star Lionel Messi as its brand ambassadors. It became the main sponsor of the Indian cricket team and an official sponsor of 2022 FIFA World Cup.

But in recent months, the company has been dogged by complaints as parents accused it of not fulfilling its promises – coercing them into buying courses they couldn’t afford and then not providing the promised services. Some also said that the firm used predatory practices to exploit customers.

Former employees complained of high-pressure sales culture and unrealistic targets. The firm has laid off thousand of employees in the past year in a bid to cut costs.

Byju’s has denied the allegations made by parents and its former staff. It has also been facing investigations from the government.

In April, the firm’s office in Bengaluru was raided by Indian authorities over suspected violations of foreign exchange laws. The company denied any wrongdoing and assured its workers that it had fully complied with the laws.

In May, lenders to the company filed a suit in a US court, accusing it of defaulting on payments and breaching terms of the loan agreement, including months-long delays in releasing financial statements. The lenders also accused the company of diverting funds through its US-based subsidiary Alpha, a claim Byju’s denied.

In June, after reportedly missing an interest payment of nearly $40m, Byju’s sued the lenders over alleged harassment.

It also began another round of layoffs, firing nearly a thousand employees. There was more trouble waiting for the firm from its own auditors.

Deloitte Haskins and Sells Llp quit as the company’s auditors citing the delay in Byju’s submitting its financial statements. The auditors said it impacted their ability to assess the company’s books.

This was soon followed by news that three of its board members had resigned, leaving just CEO Byju Raveendran, his wife Divya Gokulnath and brother Riju Raveendran on the board.

The start-up is reportedly now in talks to restructure its debt load.

Reports also said that there were calls for the CEO’s resignation at a shareholders’ meeting this week, but two investors at the company denied these claims.

“Byju’s failed at holding itself to the standard expected of a company its size,” said K Ganesh, a serial entrepreneur and angel investor who founded one of India’s largest online grocers, BigBasket.

The delay in filing financial statements was “unacceptable and unconscionable”, he says.

“Most sectors that benefited from the pandemic and expanded rapidly are now facing headwinds because the return to normal has been more drastic than they expected,” Mr Ganesh said. “This is true for all companies in the edtech sector.”

Experts say the sector’s potential was overestimated during the pandemic.

“Technology by itself will never work,” Dr Malpani explains. “You need it along with safe space for children where there is adult supervision, peer to peer learning.”

“Byju’s was essentially selling hardware, like its tablets, with study material that could be found online for free,” he says.

These start-ups were valued at a “stratospheric, unrealistic level” during the pandemic and are being valued at “realistic levels now,” Mr Ganesh said.

He added that one of the reasons Byju’s is at its current crossroads is the “detrimental” board structure of venture capitalist-funded companies.

“With just managers, founders and investors on board – each of whom is bound to protect their own interests – there is nobody to protect the interests of the company. This is unlike a public listed company where regulatory rules ensure a set of independent directors on board and insist on an audit committee headed by an independent director,” Mr Ganesh explained.

Several experts, including Mr Ganesh, have been advocating that start-ups that reach a certain level should be told to work like public listed firms.

At the shareholders’ meeting, the company is said to have agreed to form an advisory committee consisting of independent directors to advise and guide the CEO on the composition of the board and the governance structure

Mr Ganesh and Mr Shriram said the company could still course correct if it acknowledges its missteps and commits to immediate action on all fronts.

But Dr Malpani believes Byju’s has not shown the intent to do this.

“They need to conserve as much cash as possible which will give them a long runway and cut down on costs aggressively, more than just through layoffs,” says Mr Shriram. “Also, sell off some businesses to raise capital.”

Byju’s has set a timeline of September end for the completion of its 2022 audit and December end for its 2023 audit.

Analysts believe Byju’s current situation will only have a positive short-term impact on India’s start-up ecosystem.

“Due diligence, founders’ rights, the need for an internal auditor, independent board members and terms and conditions of corporate governance, which were earlier glossed over, will become stricter,” Mr Ganesh said.

“India has good corporate governance laws,” Mr Shriram said. “It is for the investors and other stakeholders to demand more from Byju’s.”

Analysts say investors are used to handling bull and bear runs and have short memories when it comes to these dips.

“There’ll be another [like this] in two years,” Dr Malpani says.

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC:

City Hall will prop up Bus Rapid Transit

The Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA) will continue the city’s Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) service when the concession granted to Bangkok Mass Transit System Plc (BTSC), a private operator of the service, ends on Aug 31.

BMA has a plan to improve the service, according to Bangkok Governor Chadchart Sittipunt. He told Isara News Agency the BMA plans to increase the number of BRT bus stops and the number of buses to improve convenience for passengers.

Currently, only 10 out of all 25 BRT busses are functioning which is why passengers have to wait for at least 15 minutes to board at present, he said.

In addition, many private cars drive in lanes reserved for the BRT service, especially during rush hour on Rama III Road, leading to delays in the BRT service.

He said BMA plans to increase the frequency of the service and will add more BRT stops near pedestrian crossings, which has proved effective in improving convenience for feeder-service passengers in South Korea. The BMA intends to adopt the same technique.

It also plans to use smaller-size buses with electric power, he said.

“We will not stop the BRT service. We will improve it,” he said.

A BMA source said a 13-million-baht budget has been set aside for hiring a company to operate the BRT and provide maintenance, and will hire other staff such as maids and security guards.

The BMA expects to have a new operator within the next month, or before the concession ends, he said. Under the present concession, BRT collects a 15 baht fare from 9,000-10,000 passengers a day, while BTSC gets its revenue from advertising fees, said the source. The operator, however, has expressed no interest in seeking to renew the concession as the service is unprofitable, he said.

At present, the BRT route stretches 16km from Narathiwat Ratchanakharin Road to the Ratchada-Ratchaphruek intersection, allowing passengers to connect to the BTS at Chong Nonsi and Talat Phlu stations.

China-led EV boom in Thailand threatens Japan’s grip on key market

CHINA VS JAPAN Bangkok resident Pasit Chantharojwong drove a Toyota Corolla for a decade and a half before switching to Great Wall’s Ora Good Cat this year. “I’ll never go back to a combustion-engine car again,” said the 55-year-old teacher, who also drives part-time for a ride-hailing service. Of theContinue Reading

No mere dress code protest

Teen activist Thanalop “Yok” Phalanchai was the centre of public attention when her anti-uniform activism kicked off in June.

Attending classes in casual outfits and with her hair bleached bright pink, many saw her resistance to Thailand’s mandated school uniform rules as heralding a hopeful shift in society while others have deemed it untimely activism.

Not long after her act of defiance made headlines, Triam Udom Suksa Pattanakarn School in Suan Luang district of Bangkok declined to enroll her to finish her high school education, citing her parents’ failure to complete the registration process.

This was despite the fact the Ministerial Regulations on Student Registration 1992 say authorised guardians are legitimate stand-ins to complete the registration process.

The public reception of Yok might have been influenced by the fact she was arrested and charged with violating Section 112 of the Criminal Code, or the royal defamation law.

Yok was arrested on March 28, the same day a 24-year-old man was caught spray-painting a “No 112” message on the wall of the Temple of the Emerald Buddha.

Police said they had a warrant to arrest the girl, accused of insulting the monarchy during a rally in October 2022 in front of Bangkok City Hall. She was 14 at the time.

Last year, she spent 51 days at the Ban Pranee Juvenile Vocational Training Centre for Girls in Nakhon Pathom before being released on May 18.

“My activism did not kill anyone. It was a symbolic act. My casual clothes did not bar me from education, it was school staff who did. This is proof that education institutions and some of my compatriots are willing to bury whoever calls for changes in society.”

Yok published these remarks on her Facebook page on June 17 in response to the overwhelming criticism she received from netizens about her anti-uniform stance.

School authoritarianism

Fellow activist Netiwit Chotiphatphaisal, 26, who challenged various social norms since he was himself at high school more than 10 years ago, told the Bangkok Post that society is looking at Yok’s activism through a different lens than it used to scrutinise his actions.

“I think society is supporting Yok more. Back [in my day], it was rare to have supporters being vocal about my activism. My activities were only reported by independent news outlets like Prachatai. Yok has been on national broadcasts and covered by big media outlets,” said Mr Netiwit.

Mr Netiwit himself called for an end to strict enforcement of rules on students’ uniforms and hairstyles.

He said schools or universities should be an open space where students can experiment with new things. Even though Yok’s anti-uniform stance may fail practically and ideologically, it should not be such a big deal if the school functions as an experimental ground.

But above the uniform and hairstyle controversies, Mr Netiwit said the real issue is authoritarianism in the school system.

“We need to dig deep into the roots of such authoritarian rules. They were initiated by an authoritarian government who opposed socialism or democracy. School uniform and hairstyle rules are only the surface of a deep-rooted authoritarianism,” he said.

The hairstyle codes were first implemented in 1972 by the military government led by Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn.

The rules were published in the first Education Ministerial Regulation, which said male students must not grow their hair longer than five centimetres while female students must not grow their hair below the earlobes. Students are not allowed to wear makeup to school either.

Fast forward 51 years, most public schools have compromised on the strict hairstyle codes. Female students can grow their hair longer but they are not allowed to let their hair down while in school. Male students can grow bangs but their sides must be cut short.

However, dyed hair, permed hair and moustaches or beards are strictly prohibited. Any students who violate such rules will face punishment such as forced hair-cuts by teachers or score deductions.

More student engagement

Yok’s case has been reviewed by the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security and Triam Udom Suksa Pattanakarn School, as a clash between a 15-year-old student and much more experienced and authoritative figures.

Ticha Na Nakorn, adviser to the Children, Youth and Family Foundation, said many saw Yok as a threat to school establishment. However, she did not reject the regulations outright.

“Some rules have been enforced for a long time. If we want an improvement, why don’t we try asking the students for their ideas?” said Ms Ticha.

She suggested public schools hold talks among teachers, students and parents on hairstyle and uniform rules. The sense of engagement will allow participants to feel like they are a part of the institution and should temper disputes over the rules.

Speaking about being an active citizen, a concept widely celebrated in schools, Ms Ticha said the public education system encourages students to be active citizens but simultaneously forces them to be docile.

“These Gen-Z students are not comfortable with adult instruction. It is a different period of time and their demands are changing as well,” she said.

However, Yok’s case is unique since she was charged with royal defamation, an allegation which arouses public sentiment. “If Yok had been just a teenage girl who wants a makeover like most girls her age do, teachers would have simply warned her not to break the rules,” Ms Ticha said.

Once facing the lese majeste charge, Yok was seen as a threat to national security. This may have led to her being rejected from admission to school, which Ms Ticha believes was undeserved.

On June 29, Sunai Phasuk, Thailand’s representative for Human Rights Watch, said Yok has been allowed to attend school in casual clothes and dyed hair.

However, some teachers have reportedly refused to grade her homework and the school cannot issue her a graduation certificate as she failed to complete the registration process.

A committee comprising the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security, the Department of Children and Youth, Triam Udom Suksa Pattanakarn School and its Parent-Teacher Association has yet to give any updates on Yok’s student status, said Mr Sunai.