South Korea’s Yoon heads to NATO summit amid North Korea, China tensions

SEOUL: South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol was set to depart on Monday (Jul 10) for a summit with North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) leaders, seeking deeper international security cooperation amid rising North Korean threats and tension over China. Yoon’s attendance at the annual NATO gathering that begins in Lithuania onContinue Reading

Six killed in kindergarten attack in China; suspect detained

A suspect has been arrested after six people were killed and one wounded in a stabbing at a kindergarten in China’s Guangdong province on Monday (Jul 10).

“The victims include one teacher, two parents and three students … and one suspect has been arrested,” said a spokesperson for the city government.

The spokesperson did not offer details about the identities or ages of the victims, nor the weapon used in the attack.

The attack in Lianjiang county happened at about 7.40am and the police arrested a 25-year-old man surnamed Wu at about 8am. The local police called it a case of “intentional assault”.

Authorities are investigating the cause of the attack.

The incident was the top-trending discussion on Weibo, a social media platform, with 130 million views as of 12.20pm.

SPATE OF ATTACKS

While guns are strictly controlled, China has been struggling with a spate of mass stabbings.

Fatal attacks targeting students and schools have occurred nationwide in recent years.

The attacks have forced authorities to step up security and prompted calls for more research into the root causes of such violent acts.

Last August, three people were killed and six others wounded in a knife attack at a kindergarten in southeast China’s Jiangxi province.

In April 2021, two children were killed and 16 others wounded when a knife-wielding man entered a kindergarten in southern China.

In June of the previous year, 37 students and two adults were wounded by a knife-wielding attacker at a primary school in southern China.

And in November 2019, a man climbed a kindergarten wall in southwest Yunnan province and sprayed people with a corrosive liquid, wounding 51 of them, mostly students.

The same year, eight schoolchildren died and two others were wounded in a “school-related criminal case” in the central Hubei province, with a 40-year-old man arrested.

And in April 2018, a 28-year-old man killed nine college students and injured 12 others outside their school in the northern province of Shaanxi.

The attacker later said he acted out of revenge after being harassed by a student at the same school.

Two questioned about German businessman’s disappearance

CHON BURI: Two foreigners were called in for questioning at Nong Prue police station in Bang Lamung district on Sunday night in connection with the disappearance of German property broker Hans Peter Ralter Mack.

The two foreigners, whose nationalities and identities were not disclosed, were accompanied by their lawyers.

Pol Col Tawee Kudthalaeng, Nong Prue police chief, said the two declined to give statements, saying their lawyers would represent them in any legal proceedings.

A woman suspected of involvement in Mr Mack’s disappearance was earlier called in for questioning. She declined to cooperate, saying her lawyer would act on her behalf.

Later on Sunday night, Pol Maj Gen Theerachai Chamnanmor, chief investigator of Provincial Police Region 2, led immigration and tourist police, with a court warrant, to search house 21/302 in Chok Chai Garden 2 housing estate at Moo 10 in tambon Nong Prue. The house belonged to one of the suspects. Police did not find anything suspicious in the house.

Sources said investigators had detected suspicious financial transactions totalling about 2 million baht which might be linked to the man’s disappearance.

Mr Mack, 62, has not been seen since July 4. His Thai wife, Piriya Boonmark, said he left their Swiss Paradise housing estate home in Pattaya in his Mercedes Benz to meet a foreign property broker he had recently met.

The family filed a missing person complaint with police on July 5 and later offered a reward of 3 million baht for information on Mr Mack’s whereabouts, and 100,000 baht on his car.

The silver Mercedes-Benz E350 coupe was found by police on Sunday morning in the CC Condominium parking lot on Khao Noi road in tambon Nong Prue. The interior surfaces had been wiped clean with a chemical cleanser.

Hans Peter Mack, the missing 62-year-old German businessman. (Photo: Chaiyot Pupattanapong)

Six dead in China kindergarten stabbing

Six people have been killed and one injured in a stabbing in a kindergarten in China’s south-eastern Guangdong province, police tell the BBC.

Police said they have arrested a 25-year-old man and are investigating the cause of the attack.

They have not revealed any details about the victims but called it a case of “intentional assault”.

They said the attack happened on Monday at 07:40 local time (23:40 Sunday GMT).

This breaking news story is being updated and more details will be published shortly. Please refresh the page for the fullest version.

You can receive Breaking News on a smartphone or tablet via the BBC News App. You can also follow @BBCBreaking on Twitter to get the latest alerts.

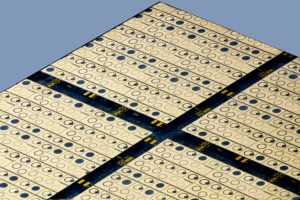

How Chinaâs gallium and germanium bans will play out

From August, China is to restrict exports of gallium and germanium, two critical elements for making semiconductor chips.

With China dominating the supply of both elements, exporters will now need special licenses to get them out of the country. The move has the potential to harm a range of Western tech manufacturers that use these elements to make their products.

The move is reportedly in response to Western restrictions on equipment vital for making semiconductor devices.

Above all, the US CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 curtailed exports of high-end microchips and technology to China, potentially affecting Beijing’s capacity for high-performance computing in areas such as defense. Other nations such as Japan and the Netherlands have also imposed restrictions.

So how important are the new Chinese restrictions and what are the implications likely to be?

Silicon is the most widely used material in semiconductors, and is very abundant. But germanium and gallium have specific properties that are hard to replicate and lend themselves to certain niche applications. These get incorporated into countless devices such as smartphones, laptops, solar panels and medical equipment, as well as defense applications.

Both elements are also crucial to technological advancement over the next few years. Germanium is particularly useful in space technologies such as solar cells because it is more resistant to cosmic radiation than silicon.

With the physical limits of silicon being approached in some technologies, increased use of germanium is mooted as a way of overcoming these limits. It is already used in small quantities in some semiconductors to improve things like electron flow and thermal conductivity.

As for gallium, 95% of it is used in a material called gallium arsenide, which is used in semiconductors with higher performance and lower power-consumption applications than silicon. These are used in things like blue and violet LEDs and microwave devices.

Meanwhile, gallium nitride is used in semiconductors in components for things like electric vehicles, sensors, high-end radio communications, LEDs and Blu-Ray players. Its use is expected to grow significantly.

Both gallium and germanium are on the European Union and US lists of critical elements. The UK considers gallium to be critical to its manufacturing interests, though sees germanium as less important.

China controls about 60% of all germanium supplies. The element is derived in two main ways, as a by-product of zinc production and from coal. These respectively account for about 75% and 25% of the total supply.

China dominates germanium that comes from zinc production. The US is one of the alternative suppliers, with deposits in Alaska and Tennessee and additional refining capacity in Canada. But as it stands, the US is still over 50% reliant on imported germanium.

Germanium from coal has several drawbacks. Two of the main producers are Russia and Ukraine, and the war has affected supplies to the west from both countries. In the years 2017-20, Russia was supplying 9% of the US germanium requirement, for instance, but this is now likely to have stopped.

In response to the Chinese restrictions, Russia plans to increase germanium production for its domestic market. This may at least alleviate global demand, even if it won’t help the West directly.

Germanium from coal is also at the mercy of the power industry, since certain coals rich in the element are burned as an energy source. In addition, germanium from coal will become more difficult as much of the world seeks to phase out coal power, which again could tighten supplies.

With gallium, China accounts for around 80% of the world supply, deriving it mainly from aluminum production. There’s actually no shortage of gallium, but even before the new controls, the supply was restricted by a lack of production capacity.

Gallium is also obtained by recycling semiconductor wafers, which are thin slices of semiconductor used in electronic circuits. But once the circuits are integrated into products, the quantities of gallium in each one are so small that it becomes challenging to recycle.

A Nature Communications paper in 2022 noted that gallium is “almost never functionally recycled” once it reaches final products.

The full impact of China’s new export regime depends on a number of factors, including the severity of the controls in practice, and the response of Western governments and companies. As it stands, the controls look likely to lead to higher prices for gallium and germanium, as well as longer delivery times.

This could make it more expensive and difficult for Western companies to produce electronic devices, which could in turn lead to higher prices for consumers. It could also make it more difficult for Western companies to compete with Chinese companies.

In an echo of how the global microchip shortage during the Covid pandemic considerably affected tech manufacturing, this points to a significant impact on the global economy.

The long-term effects of the controls are difficult to predict because so many factors are involved. Stockpiles of the elements should help to some extent: the US has said it holds inventory of germanium, though not gallium.

Western manufacturers may be forced to diversify their supply chains by obtaining components containing the elements from countries to which China is willing to export. This could lead to increased costs and complexity.

Another avenue is to increase production from alternative sources. In the past, germanium has been derived from minerals mined in Germany, Latin America and Africa, so these options may come back on the table. There is also the potential to invest in researching devices that are less reliant on these critical materials, but that would take time to bear fruit.

Clearly, the move is a significant escalation in the tech war between China and the West. The concern is that it could go further: China dominates the supply of a whole range of vital materials known as rare earth metals, as well as other materials which are required for the clean energy transition. Even before the escalation in hostilities over the past couple of years, China had used its dominance over certain materials as leverage in trade disputes.

So this latest development is concerning to say the least. At a time when the international challenges faced by humanity are greater than ever, the emergence of a new resource nationalism is the last thing anyone needed.

Gavin D J Harper, Research Fellow, Birmingham Centre for Strategic Elements & Critical Materials, University of Birmingham

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Singapore’s cultures can grow stronger by evolving, learning from each other: Tharman

SINGAPORE: “Xiang hu jing zhong”. As he uttered these words, which mean “respect for all”, former Senior Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam received cheers and applause on Sunday (Jul 9) at his first public event since he left his government posts. Clad in a signature batik shirt alongside his wife who donnedContinue Reading

Japan sea sludge tells story of human impact on Earth

That perfect preservation is the result of several unique characteristics, explained Yusuke Yokoyama, a professor at the University of Tokyo’s Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute, who has analysed core samples from the site. The bay floor dips down quickly from the shoreline, creating a basin that traps material in theContinue Reading

Is there an opportunity for Malaysia in carbon capture?

46 trillion cubic feet of potential carbon storage capacity identified

Tax incentives were announced in Budget 2023 to spur activity

Malaysia has pledged to cut carbon intensity against GDP by 45% by 2030 compared to 2005 levels, in line with its commitment to achieving carbon neutrality by 2050. As previously reported by…Continue Reading

One dead as Japan warns of ‘heaviest rain ever’ in southwest

TOKYO: One person is dead and three missing in landslides in southwestern Japan, authorities said on Monday (Jul 10), as the country’s weather agency warned of the “heaviest rain ever” in the region. A 77-year-old woman was confirmed dead in a landslide that entered her home overnight in rural Fukuoka,Continue Reading

The rush for nickel: ‘They are destroying our future’

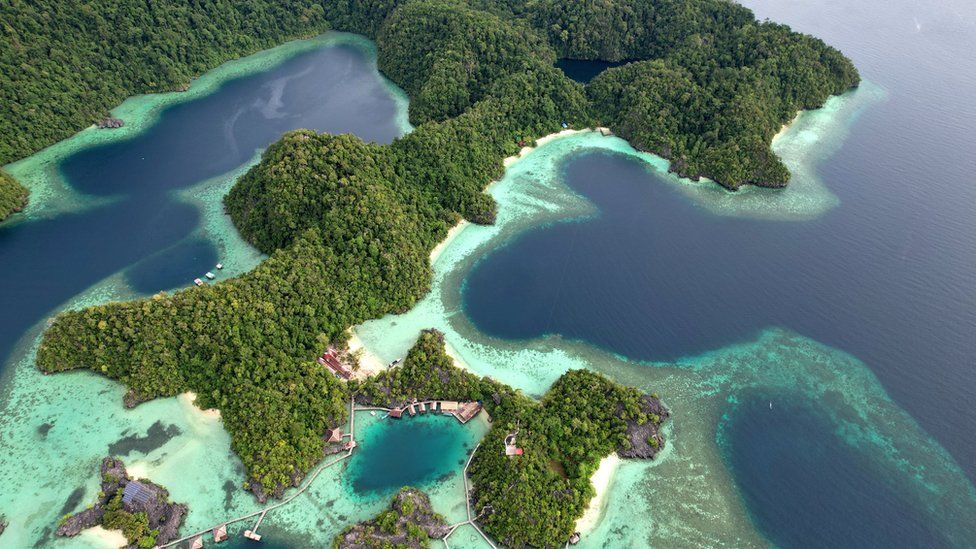

Two men are carrying torches and homemade arrows as they slip into the ocean at night on an Indonesian island.

They are from an indigenous community of Bajau people – renowned freedivers who find it better to hunt in the dark when fish, lobsters and sea cucumbers are less active.

But they fear time is running out for their traditional way of life.

“Right now, the water is still clear,” says Tawing, one of the fishermen. “But it won’t stay that way… nickel waste enters our water during the rainy season and the current carries it here.”

Nickel is an integral part of global life, used in stainless steel, mobile phones and electric car batteries. As the world shifts to greener vehicles and needs more rechargeable batteries, the International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts that demand for nickel will grow by at least 65% by 2030.

The IEA expects Indonesia, the world’s largest nickel producer, to meet two thirds of the world’s needs for the metal. The country has already signed deals worth billions of dollars with international players keen to invest in processing plants as well as mines.

But conservationists warn that mining could have a devastating effect on the environment.

Here on Labengki Island in Southeast Sulawesi, Tawing fears that if the government does not take action, waste from nickel mines will end up in the sea, damaging the island and surrounding marine life.

According to data from the Indonesian government, about 50 nickel mining companies currently operate in North Konawe Regency, across the water from Labengki Island.

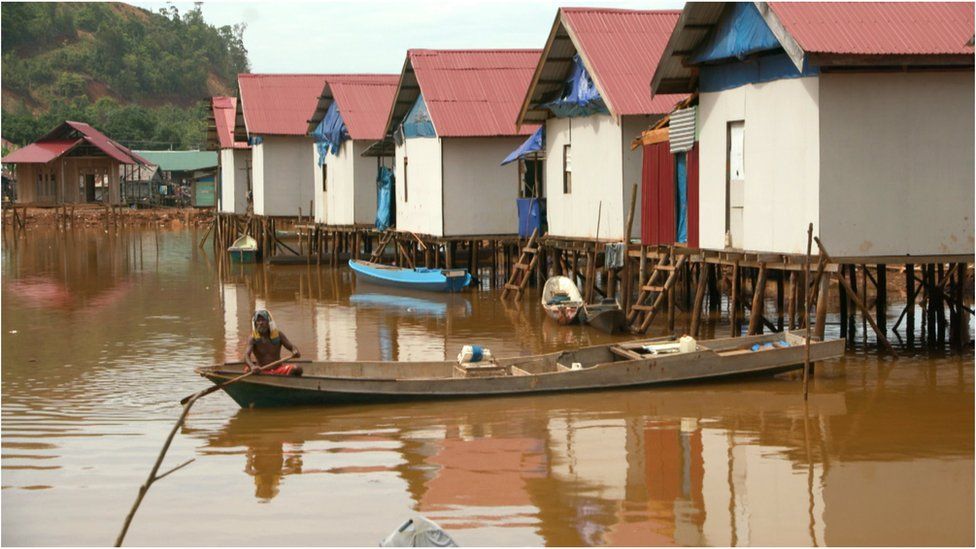

The journey to get there takes us about an hour by boat. As we approach, the green hills are replaced by brown, deforested patches. Excavators and barges can be seen digging and carrying the “new gold”. The water beneath us is a reddish-brown colour.

In the coastal village of Boenaga we meet Lukman, another Bajau fisherman, who says he can no longer fish near his home.

“We couldn’t see anything underwater when we dived,” he says, pointing at brown water at the back of his house. “We could hit a rock.” The cost of fuel makes it impractical for him to travel further afield to fish and he says if they make a fuss the police end up getting involved.

In order to mine nickel, large areas of trees are cut down and the land is excavated to create open pits. With the roots of the trees no longer present to stabilise the ground, when it rains earth is more easily swept away.

Government data shows that in 2022 there were at least 21 floods and mudslides in Southeast Sulawesi. Between 2005 and 2008, before the proliferation of mines, there were two to three per year, according to the National Agency for Disaster Countermeasure.

Chemicals such as sodium cyanide and diesel can be also used in the mining process. That worries local conservationist Habib Nadjar Buduha, who says that when waste material and water are not properly managed, sediment ends up in the sea.

He showed me a video he shot about 10 miles along the coast, off Bahubulu Island, of a coral reef “suffocated” by sediment.

He is afraid that the same thing will happen in Labengki and in 2009 he founded a conservation group to protect giant clams. “They would never win against nickel pollution,” he says.

“The sediment will bury and destroy them.”

Individual nickel mining companies near Boenaga did not to respond to our requests for comment, but we did speak to the Indonesian Nickel Miners’ Association – about half of the mining companies in North Konawe are members.

The secretary general, Meidy Katrin, says that in order to get a licence companies must agree to carry out reforestation or reclamation of the land when they have finished mining an area.

“The question is, are the companies doing it?” she says, admitting there are patches of bare land that have not been reforested. But she says this may not be the fault of companies with permits: “This area also has a lot of illegal mining activities.”

She puts the onus on the government to check up on miners to make sure they are complying with the rules and ensure that what they put in their reports matches the reality.

The head of Boenaga village, Jufri Asri, sees things differently to Lukman and Habib. He believes the mines have brought benefits to his community. “Take the price of fish,” he says. “I don’t take fish to the city to sell because the price is higher here. These companies need fish too.”

His 21-year-old son has a job at a nearby nickel mining company and, like other families in Boenaga, they receive a monthly compensation fee of at least $70 a month from the mines.

Financial agreements are common and are designed to offset any inconvenience caused by mining activity and heavy vehicles travelling past homes as they go to and from the pits. Jufri notes that if nickel production increases, the amount of compensation they get also goes up.

In the capital, Jakarta, we meet Novita Indri, a campaigner for Trend Asia, an NGO that promotes sustainable development. She blames the authorities for being “too weak” – she wants to see higher environmental standards and tougher regulation.

“We don’t have a track record of sustainable mining yet,” Indri says. “Indonesia has a lot of homework to do, strengthening law enforcement, increasing emission standards, and implementing environmental regulations.”

When we put this to the adviser to the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (ESDM), Professor Irwandy Arif, he tells us the government is concerned “about the impact of mining activities on coastal sedimentation”, not just in this region but across Indonesia.

However he believes pollution is caused by illegal nickel mines, not licensed companies.

He insists regulations mean that legitimate operators have water management systems in place to ensure nothing dangerous ends up in the sea and he does not believe they would ignore the rules and risk losing their permits.

But Prof Arif acknowledges that at illegal mines without treatment systems “the soil will just be eroded”.

He tells us that anyone who doesn’t comply with the regulations is prevented from selling nickel and that two illegal miners have been taken to court in the North Konawe Regency – the area where Boenaga is located.

But Prof Arif admits supervision needs to improve: “Illegal mining exists everywhere in Indonesia,” he says. “So far we have not managed to regulate it properly… we need to map which ones are legal and which ones are illegal so that we can minimise this environmental damage.”

He points out that in order to try to improve the situation, the government recently established a national illegal mining taskforce.

But many of the Bajau people we spoke to say change is not happening quickly enough. If things continue as they are, conservationist Habib warns that the damage could be irreversible.

“What they are destroying is our future,” he says.