Back in 2015, there was immense optimism surrounding the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), with expectations that it would elevate Pakistan’s global standing and position it as a leading force in South Asia. However, what was initially hailed as a well-intentioned effort to strengthen the bilateral relationship has become one of the primary factors contributing to Pakistan’s economic decline.

While there were a few significant Chinese-backed infrastructure projects in Pakistan prior to CPEC, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) ushered in a new era for Pakistan’s struggling public-sector projects and its chronically weak power and transportation industries. These sectors had long relied on government subsidies, leading to budget deficits.

After China announced its intention to support Pakistan and promote its ambitious Silk Road Economic Belt initiative, CPEC quickly emerged as the flagship project of the BRI.

Introduced in May 2013 during Chinese premier Li Keqiang’s visit to Pakistan, the economic corridor was lauded for its design, addressing Pakistan’s infrastructure gaps, establishing industrial zones, and creating trade routes to China through the strategically located Gwadar Port on the Arabian Sea.

The project initially required a substantial investment of US$46 billion, which quickly escalated to $62 billion in pledges, accounting for around 20% of Pakistan’s GDP. It encompassed several significant Early Harvest Projects (EHPs) in a country in dire need of international investment.

From a geopolitical standpoint, India has been a vocal opponent of the BRI since its inception in 2013. India viewed one of the key components of CPEC as a violation of its territorial integrity and sovereignty, particularly in relation to its claims on Pakistan-controlled Kashmir.

The initiative was seen as part of China’s broader strategy to encircle India and gain influence in the region. Concerns also arose regarding China’s easy access to Pakistani ports and the potential establishment of a naval base, raising significant security apprehensions for India.

India opted to oppose the BRI and focused on its own connectivity initiatives, such as the International North-South Transport Corridor and the Chabahar port in Iran, although it lacked a comprehensive strategy to enhance regional connectivity.

Initially, the introduction of the CPEC project brought hope and relief to the people of Pakistan, who had been grappling with persistent power and energy issues. Widespread blackouts caused by severe power shortages had paralyzed economic activities and cast bustling market areas into darkness.

The energy crisis stemmed from exorbitant energy rates charged by independent power producers (IPPs), neglected power plants, deteriorating transmission lines, and years of populist government policies.

For more than three decades, citizens endured daily electricity outages of about 10 hours in urban areas and up to 22 hours in rural regions. These power cuts disrupted revenue-generating markets, industries, educational institutions, health-care facilities, and social activities.

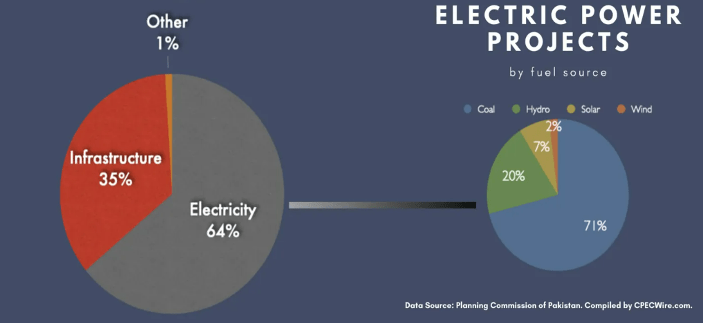

Figure 1: Division of CPEC Projects

China’s initial focus on constructing new coal-fired power plants within the framework of CPEC was initially seen as a positive step. However, in late 2021, China shifted its stance to align with the objectives of the UN Climate Change Conference (COP26), committing to avoid developing coal-fired power plants overseas and striving for carbon neutrality.

This change had dire consequences for Pakistan’s coal-dependent power sector, as ongoing CPEC projects aimed at expanding the country’s power-generation capacity by 20 gigawatts were halted or shelved.

The economic viability of CPEC projects, along with Pakistan’s ongoing financial distress and its involvement in the “war on terror,” further complicated the situation. Rumors of impropriety on the Chinese side added to the challenges, leading to project delays and an increasing burden of unproductive debt.

While Pakistan’s unsustainable external debt and economic difficulties predated the CPEC agreement, the initiative exacerbated the country’s widening current account deficits and depleted foreign-exchange reserves. Despite recommendations from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Pakistan imported significant volumes of materials for the projects before seeking a $6.3 billion bailout from the intergovernmental body.

The foundation of CPEC, heavily reliant on Chinese equity holdings in Pakistan’s infrastructure projects, has made Pakistan liable for 80% of the investments related to the corridor. This has raised concerns that the former flagship initiative of the BRI is flawed and a costly misstep for China.

China has consistently refused to defer or restructure pending debt repayments, fearing that it would set a precedent for other debtor nations and result in a collapse of bad loans. However, it is in China’s interest to assist Pakistan in maintaining its image as a reliable ally to the developing world.

Given these circumstances, it is crucial for economies in the region, particularly BRI countries like Pakistan, to monitor closely and manage the share of China’s debt in their total external debt.

Pakistan’s involvement in CPEC has led to impractical projects heavily reliant on foreign loans, exacerbating the country’s economic difficulties. Soaring trade deficits and low levels of foreign direct investment have been caused by excessive reliance on external borrowing without addressing underlying macroeconomic challenges.

Therefore, Pakistan needs to prioritize credit diversification and debt restructuring to regain control of its external sector and tackle the pressing macroeconomic issues at hand.

A more detailed article by this author can be found here: Debt ad Infinitum: Pakistan’s Macroeconomic Catastrophe.