Risk gauges in Germany’s government debt market rose last week to levels higher than recorded in the 2008 world financial crash, as margin calls forced the liquidation of derivatives positions held by banks, insurers and pension funds.

Big institutional investors that spent the past ten years insuring their portfolios against falling interest rates now face massive losses as hedges blow up. A key measure of market risk, the spread between German government bonds (Bunds) and interest rate swap agreements jumped above the previous record set in 2008. The cost of hedging German government debt with interest-rate options, or option-implied volatility, meanwhile rose to the highest level on record.

The blowout in the euro derivatives market follows a near-collapse of the British government debt, or gilts, market, averted at the last minute by a £50 billion bond-buying spree by the Bank of England.

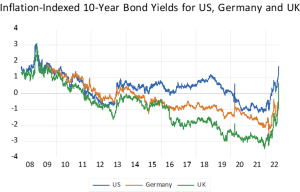

The world’s central banks responded to the 2008 world financial crash and the European financial crisis of 2011 by pushing bond yields down.

“Real” yields, namely the yield on inflation-indexed government bonds, went deeply into negative numbers in Germany and the UK, followed by the US market. That pulled the rug from under insurance companies and pension funds, which invest pension payments and insurance premiums to provide for future income.

To compensate, European and UK institutions locked in long interest rates with derivative contracts, or interest-rate swaps, that receive a long-term interest rate while paying a short-term interest rate. Swaps are a leveraged position that requires collateral worth a fraction of the notional amount of the contract.

When the Fed jacked up interest rates in late 2021, the value of interest rate swaps that pay fixed and receive floating imploded. Pension funds and insurers were stuck with the equivalent of a ten-to-one margin position in long government bonds. The price of long government bonds fell by nearly 20% across the Group of Seven countries, and the value of derivatives contracts evaporated.

That left the institutions with margin calls that they could meet only by liquidating assets. That in turn led to a run on the UK government bond market, followed closely by the rest of European bond markets. The Bank of England’s emergency bond-buying delayed a market crash, but the UK gilts market remains on a knife edge, with option hedging costs at an all-time high.

A portfolio manager at one of Germany’s largest insurance companies said, “It’s a global margin call. I hope we survive.”

Weaker European banks may have trouble finding short-term funding. The cost of credit default swaps that insure 5-year bonds of Credit Suisse is now higher than it was in 2008, at nearly 400 basis points (4 percentage points) above the cost of interbank funding. The venerable Swiss institution is a special case, with a series of losses due to poor risk controls. Credit Suisse probably will survive – bank regulators will force it to sell assets and shrink – but it will also call in collateral from customers.

American pension funds and insurers haven’t faced the same kind of margin calls, but they stand to suffer painful losses. As interest rates fell, they shifted to real income-earning assets like commercial real estate. The value of commercial real estate investment companies on the US stock market has fallen by 35%, about the same amount as the tech-heavy NASDAQ Index. If that’s any indication, the $20 trillion value of the commercial real estate market has lost about $7 trillion this year, in addition to losses of nearly 20% on corporate bond and stock portfolios.

Stocks and bonds, the largest components of pension portfolios, are down about 20% during 2022.

European stocks are down 30% in dollar terms, and Japanese stocks are down by 25%. The publicly traded stock of private equity firms like Blackstone and KKR has lost 35% during 2022 to date.

All in – depending on which survey of pension fund asset allocation you believe – the average US pension has probably lost more than 20% of its asset value this year.

The Fed-driven asset bubble of the past ten years brought US pension funds up to minimum funding requirements to meet liabilities as of 2021. Now the Fed may take it all away again, and the biggest problem for major US corporations may be unfunded pension fund liabilities.