Japan has called on China to remove a total ban on its seafood products, imposed after Tokyo began the scientifically-endorsed release of treated water from its Fukushima nuclear plant.

China, the leading buyer of Japan’s fish, announced on Thursday it was making the order due to concerns for consumers’ health.

However, the claim is not backed by science – with the consensus from experts being that the release poses no safety risks to ocean life or seafood consumption.

“The main reason is not really the safety concerns,” international trade law expert Henry Gao told the BBC. “It is mainly due to Japan’s moves against China,” he said, noting Japan’s closer alignment to the US and South Korea in recent years.

Following the waters’ release on Thursday, International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) monitors at the site said their tests showed the discharge had even lower radiation levels than the limits Japan has set – 1,500 becquerels/litre – which is about seven times lower than the global drinking water standard.

And despite Japanese fishermen’s fears, analysts say the trade hit to Japan’s industry will be short-lived and less than expected.

The main market for Japan’s fish remains its domestic one.

Locals consume most of the catch, so top seafood companies Nissui and Maruha Nichiro have both said they expect limited impact from China’s ban. Both companies’ stock prices were slightly up at close of trade on the day of the ban’s announcement, Reuters reported.

Beyond China, no other country has even hinted at a total ban – South Korea still bans seafood imports from Fukushima and some surrounding prefectures.

Experts say even people who scoff down lots of seafood will be exposed to only extremely low doses of radiation – in the range of 0.0062 to 0.032 microSv per year, said Mark Foreman, an associate professor of nuclear chemistry in Sweden.

Humans can safely be exposed to tens of thousands of times more than that – or up to 1,000 microSv of radiation per year, Associate Prof Foreman said.

Price to pay is not so high

Japan’s government has admitted the local fishing industry will likely take a significant hit.

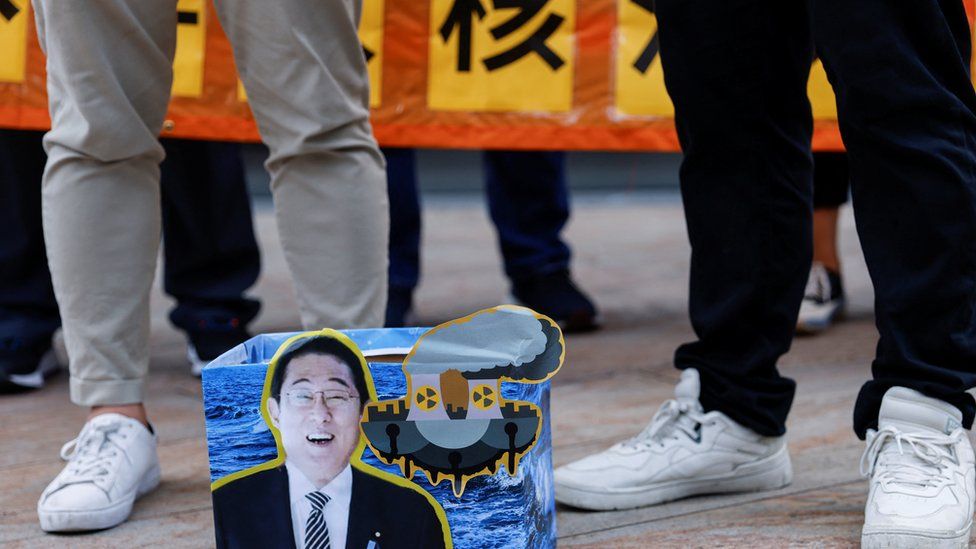

It had previously criticised Beijing for spreading “scientifically unfounded claims”, and on Thursday evening, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida again beseeched Beijing to look at the research.

“We have requested the withdrawal (of China’s ban) through diplomatic channels,” Mr Kishida told reporters on Thursday night. “We strongly encourage discussion among experts based on scientific grounds.”

China and its territories Hong Kong and Macau – had already instated a partial ban on seafood from some Japanese areas- but authorities now expanded that net.

Mainland China and Hong Kong are Japan’s biggest international seafood buyers respectively, buying about $1.1bn (£866m) or 41% of Japan’s seafood exports.

Local media reported that following China’s ban, the head of a Japanese fisheries association called Japan’s Industry Minister, urging him to lobby Beijing to retract the ban.

But industry watchers are calm, knowing the usual vagaries of supply and demand in global trade.

Prof Gao said he expects some short-term disruption but “soon the exporters shall be able to shift to other markets so the long-term effect will be small.”

And on the other side of the trade, restaurants in Chinese cities won’t be lacking in seafood delicacies. Japan supplies just 4% of the seafood China buys from abroad- Beijing buys much more from India, Ecuador and Russia, according to Chinese customs data cited by Reuters.

China’s ban on seafood will also barely scrape Japan’s overall economy.

Marine products make up less than 1% of Japan’s global trade, which is driven by car and machinery exports. Analysts say the impact of a seafood ban is negligible.

“The Fukushima water release is mostly of political and environmental significance,” Stefan Angrick, an economist at Moody’s Analytics, told Reuters.

“Economically, the ramifications of a potential ban on Japanese food shipments are minimal.”

Still, public perception around the industry’s damage and safety persists, not just in China, but South Korea where there have been crowds protesting.

In the months leading up to the water’s release, fishermen in South Korea reported a notable decline in the sale value of their catch – but prices remained stable the day after the release.

At home in Japan, polling also shows a divide. The government has made significant efforts to both reassure citizens and appease the industry. It has promised subsidies and an emergency buy-out if seafood sales dive.

On Friday, Osaka authorities proposed to serve Fukushima seafood at government buildings. Meanwhile, the company running the Fukushima plan, Tepco, said it would also provide compensation to local businesses if they suffered poor sales.

But locals are also hardy. Following China’s announcement on Thursday, many Japanese on Twitter even celebrated the ban – wryly suggesting it could mean cheaper fish at home.

“Good news amid inflation…. Even Hokkaido sea urchin will be super cheap,” one user tweeted.