I’ve been calling for the US to promote manufacturing for decades. When American started getting excited about reindustrialization,  , I cheered. I was a strong supporter of Joe Biden’s business plan, and I actually praised Donald Trump for breaking the free-trade discussion in his first word.

Trump’s levies haven’t changed my mind about any of that. Indeed, the taxes are a disaster. But they’re not a catastrophe because they promote manufacturing, however,  , they are  , deindustrializing , America , as we speak, by destroying American companies ‘ ability to leverage supply stores and trade areas.

Given the harm that Trump will have caused, it will be time for America to turn once more to the task of reindustrialization when America ultimately realizes the futility of his strategy. In fact, the task will be even more serious.

And yet at the same day, I think there’s a mistaken tale about globalization, production, and the American middle class that has taken hold across much of society. The narrative is roughly this:

In the 1950s and 1960s, America was a chimney business. We created everything we needed for ourselves using union stock jobs, which created a broad-based middle course. Next we opened up our nation to business and modernization, and things started going downhill.

Pay decreased as a result of international competition, and skilled manufacturing jobs were exported elsewhere. British cities hollowed out, and we became a state of winners and losers. While the upper middle class, which had received their degrees from colleges, was forced to accept lower-wage company function, the upper middle class, who had been educated, did well in their professional careers. Finally, the fury of the oppressed working group boiled over, resulting in the election of Donald Trump.

This narrative is at work in Joe Nocera ‘s , a recent, extensively discussed post , and in the Free Press:

No one again, on the left or the right, denies that modernization has fractured the US, both economically and socially. Formerly prosperous places like North Carolina’s furniture-producing parts and the Midwest’s auto-producing regions have been hollowed out. It has been a vehicle of money inequality…Trump owes much of his social success to the indignation that these experiences aroused in working-class Americans.

According to Financial Times journalist Rana Foroohar,” My grandfather ran companies in the Detroit supply-chain orbit.” ” In the 1990s, the companies started shutting over. And third of my high school classmates were taking drugs when I returned home in the 2000s. She added,” The economic theories didn’t connect with the real world”.

Which leads me to wonder why so many economists, politicians, and journalists have been avoiding the problems with liberalism for so long. Why were we therefore quick to label anyone who even flirted with the idea that maybe the US should be protecting its business center, just as other states did, as a Pat Buchanan-like stupid?

One of the most fundamental reasons was the one that meant lower rates. Companies could keep their costs low by using China’s ( and Mexico’s ) comparative advantage: cheap labor. At the same time, businesses like Walmart and Costco may purchase products straight from Chinese manufacturers, which were consistently less expensive than equivalent American products.

And you can view the tale at work in , a new set of tweets , by Talmon Joseph Smith:

This one has layers of story wrapped around a core of truth, like all other narratives of this nature. But not all great economic stories are created equal — in this case, the layers of story are heavy and tasty, while the core of reality is thin and brittle.

All is aware of the China Shock paper and the 3 million-percent decline in manufacturing employment in the 2000s. That’s the key of the account, and it’s very true. However, there are many significant, significant economic details that most people who are discussing this topic don’t know about.

Unfortunately, the trade-driven decline in production was just a little part of the economic story of America over the last quarter century.

America is not that advanced in the global world.

Experts and politicians alike talk endlessly about the flood of cheap Taiwanese products into America. However, this accounts for only a small portion of our purchases total. The U. S. is basically an unusually , closed-off , business, as a proportion of GDP, exports are significantly lower than in most wealthy places, and lower even than China:

Trade deficits , are an even smaller proportion of GDP. About 4 % of GDP is produced in the US, less exports, excluding exports. Our trade deficit with China is , about 1 % of GDP.

America manufactures the majority of the aspects it uses in its production, in terms of imported parts. China’s exports to the US are really more likely to be middle goods rather than the customer goods we see on the shelves of Wal-Mart— another issue the usual storyline misses.

However, China only produces about 3.5 % of the intermediate products that American companies require, despite this fact:

But if we eliminated business deficits, did it reindustrialize America? The effect on manufacturing’s share of US GDP may remain relatively small, perhaps assuming that we replaced the goods 1-for-1 with domestically made products. These ‘s , Paul Krugman:

The United States had a manufacturing trade deficit of about 4 % of GDP last year. Suppose we presume that this imbalance subtracted an identical sum from spending on US manufactured products. What may occur if that gap were to be miraculously eliminated?

Also, it may increase the share of manufacturing in GDP — currently , 10 percent , — by , less , than 4 percent positions, because manufacturing companies buy a lot of services. According to a rough estimate, manufacturing value-added would increase by about 60 % of the sales change, or 2.5 percentage points, implying that the developing industry would be roughly a third larger than it is.

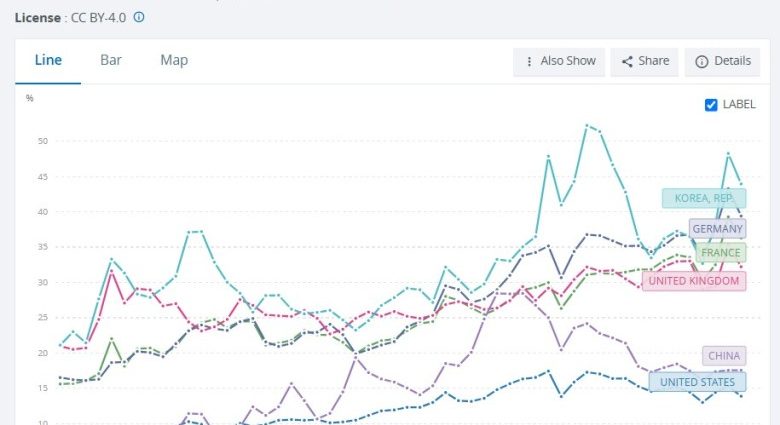

But even under the ideal situation, if we completely eliminated the US business deficit, production would go from 10 % of US GDP to 12.5 % — about the same as its share in 2007, and also far less than Germany, Japan or China:

As Nocera claimed, the production share of GDP is declining outside, as you can see from this graph that different countries haven’t done an amazing job of protecting their business foundations.

And this map is also a glimpse that trade deficits and developing aren’t as tightly linked as most people seem to think. France has gradually lost its manufacturing industry since 1960 despite the fact that it previously had quite balanced trade and even ran significant trade surpluses in the 1990s and 2000s.

However, out of all the countries on the table, Japan has done the best job of preserving its production promote since 2010, despite , running a business deficit , over that time period.

There are much bigger forces at work there than we usually do trade, which is why we tend to concentrate so much on the impact of trade on US manufacturing. Most of what the US consumes is made here, and most of what the US produces is consumed here, and eliminating trade deficits wouldn’t change either of those basic facts.

The middle class in America was never created.

Americans, as a people, are startlingly rich. This is not just because a select few very wealthy people make the average. If you take median disposable household income, the US comes out way ahead of the pack:

Note that this includes taxes and transfers, including in-kind transfers like government-provided health care.

Although middle-class Americans are wealthier than middle-class Americans are in other nations, their manufacturing industries may have been protected by other countries.

And middle-class Americans ‘ income has  , not , been stagnant over the years. Real median personal income is shown here, which is unaffected by the switch to two-earner families:

This is an increase of 50 % since the early 70s. Of course, there are ups and downs to it, but 50 % is nothing to be sniffed at.

As for middle-class wages, they’ve grown less than incomes, since some of the increased income has been in the form of corporate benefits ( health care, retirement accounts ), investment income, and government benefits. But they continue to grow:

Wage growth has resumed since the mid-1990s,  , despite , increasing trade deficits. Take note that the China Shock, which forced millions of factory workers from their jobs, completely failed to stop wages from rising again.

Wage stagnation and hyperglobalization just don’t line up, timing-wise. Another excellent chart by Jason Furman, which clearly demonstrates this:

A lot of commentators have gotten so used to the idea that incomes are stagnant that they , have trouble believing this data is correct.

However, as Adam Ozimek points out, the Economic Policy Institute, a pro-union think tank that frequently criticizes wages as being too low, chooses , a very comparable measure , for median wages. EPI writes that wages “have not been stagnant”, but “have…been suppressed”.

And when we examine the working class and the poor, where the wage distribution is at its lowest percentile, we see that they have increased even more, by over 40 % since 1996:

A$ 4/hour raise ( adjusted for inflation ) might not sound like a big deal, but for a poor person, it’s pretty huge.

Of course, as Autor and al. show in , their famous” China Shock” paper, the harms from Chinese import competition were concentrated among a few workers in a few regions. 2 million workers made up only 1.5 % of the US workforce at the time, but for that 1.5 %, being fired from good manufacturing jobs was a severe blow.

But even in those unlucky regions, the negative effects don’t look to have been permanent. Nocera claims that the poor in Flint, Michigan and Greensboro, North Carolina are “hollowed out,” but Jeremy Horpedahl points out that middle-class wages have increased while wages for the poor have increased in the latter:

And when we consider median income, the two regions appear to have recovered from their economic health over the past ten years:

( Nor is this a composition effect from people moving out, Flint’s population has  , held roughly steady, while Greensboro’s population has  , continued to increase smoothly. )

If the good manufacturing jobs of the past are all gone, how are the middle class and working class in America prospering? Talmon Joseph Smith scoffs at” service economy jobs”, and Autor et al. find that manufacturing workers who have been displaced by Chinese imports frequently choose less lucrative, crappier jobs in the service sector.

But that describes the 2000s. The 2010s and 2020s have been very different. Deming et al. According to the data from ( 2024 ), the boom in low-skilled service-sector jobs has reversed over the past 15 years, and Americans are now rushing into higher-skilled professional service jobs:

” Go to college” turns out to have been good advice. In industries like management, STEM, education, and health care, there are the boom jobs of the new era:

It took a couple of decades, but we’re finding that Bill Clinton was right — the average American is smart and competent enough to do knowledge work. And wages and incomes are showing it.

Now, none of this is to say that manufacturing is unimportant. It’s obviously, and it’s important for national defense. I also think it’s important for building a balanced, well-rounded economy — adding high-tech manufacturing on top of America’s knowledge industries would make us , even richer, and would help us pump up exports and take advantage of , multiplier effects. After decades of stagnation, manufacturing is also ripe for a productivity boom.

But the master narrative of protectionism is simply much more myth than fact. Yes, the 2000s saw some negative effects from Chinese import competition. But overall, globalization and trade deficits are not the main reason that manufacturing’s role in the US economy has shrunk. The middle class has not been hollowed out by globalization, which is contrary to what the term suggests.

Once we accept that this common protectionist narrative is deeply flawed, we can begin to think more clearly about trade policy, industrial policy, and a bunch of other things.

This article was originally published on Noah Smith’s Noahpinion , Substack, and is republished with kind permission. Become a Noahopinion , subscriber , here.