BRICS Summit host Russian President Vladimir Putin disappointed both anti-colonial enthusiasts and Western alarmists last week by conceding that the bloc’s members “have not built and are not” building a payment system to challenge the US dollar-based global banking system.

The leaders of the two economic giants present at the summit, China’s Xi Jinping and India’s Narendra Modi, did not mention alternative payment arrangements in their respective remarks.

The technical requirements for alternative payment systems aren’t the problem. The SWIFT system that controls interbank payments in dollars and other major Western currencies merely transmits secure messages.

The challenge, rather, is economic: US demand for imports fuels an outsized portion of economic growth in the Global South. China’s exports to the US amount to just 2.3% of its GDP, but about half of its surge in exports to the Global South since 2020 depends on re-exports to the United States.

While China’s exports to the Global South more than doubled from about US$60 billion a month to $140 billion a month, US imports from the Global South rose from about $60 billion a month to $100 billion a month during the past four years.

Dependence on the US market varies widely across the universe of developing countries. Vietnam and Mexico, the two favorite venues for so-called “friend-shoring,” that is, transferring production away from China to putatively friendlier countries, registered big increases in exports to the US as a share of GDP.

Vietnam’s exports to the US in 2023 amounted to about 27% of the country’s GDP, compared to just 10% in 2020, while Mexico’s US exports rose to 27% of GDP in 2023 from 20% in 2010.

Singapore and Malaysia, by contrast, showed little increase in US exports as a share of GDP. Indonesia and Brazil export comparatively little to the United States.

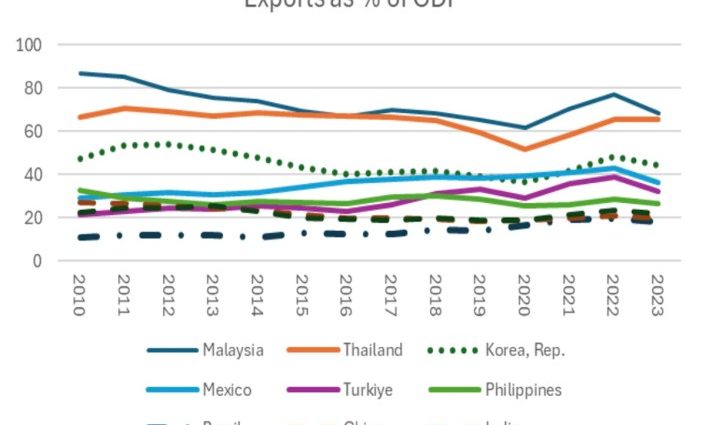

Some Asian countries, notably Malaysia and Thailand, export more than 60% of their GDP, mainly to other Asian countries. Brazil, Indonesia and China are far less export-dependent.

Today, China exports just 19% of its GDP compared to 27% in 2010, which means that an increasing share of GDP growth depends on domestic consumption and investment.

What makes the United States such an important factor in the economies of the Global South is its enormous current account deficit. The table below ranks the current account surpluses and deficits of the 20 largest economies from the largest deficit to the largest surplus.

With a current account deficit of $80 billion a month, or $1 trillion a year, the US appetite for an excess of imports over exports dwarfs the rest of the world.

China is the largest or second-largest economy in the world, depending on whether we count GDP in US dollars or adjust for purchasing power parity, but China’s imports from the Global South have been stagnant for three years.

China won’t replace much of American import demand for the time being, given Beijing’s focus on high-tech investment rather than consumer demand. At the margin, that leaves the Global South all the more dependent on the US.

Projecting current trends into the future suggests a steady rise in consumer spending in the Global South, especially in East Asia, and the emergence of robust domestic markets and less dependence on exports.

Below is a chart published by the Brookings Institution think tank last year, projecting that the total consumer market in East Asia will overtake the US consumer market by 2028.

Developing countries, though, don’t pay their bills on projections. Arranging payments for goods in international trade is a trivial issue. More challenging is financing long-term deficits.

India, for example, used to run an annual trade deficit with Russia of less than $3 billion. Discounted Russian oil sales to India after the start of the Ukraine war boosted this to more than $60 billion.

What will Russia do with the Indian rupee equivalent of $60 billion? It would far prefer to have another currency, for example, the UAE dirham, that can be used to buy goods in third markets.

The Global South doesn’t yet have the capital markets or the currency stability to convince a surplus trading country to simply hold assets of the deficit country in exchange for goods.

That is what the United States does so well: Its $18 trillion negative net foreign asset position corresponds to the last 30 years’ cumulative current account deficits.

America sells assets to foreigners in return for their goods. The Global South doesn’t have the assets to sell, or at least not in the form that the rest of the world would like to own.

That helps explain why the BRICS Summit’s final declaration relegated the issue of payment systems to feasibility studies:

We reiterate our commitment to enhancing financial cooperation within BRICS. We recognize the widespread benefits of faster, low-cost, more efficient, transparent, safe and inclusive cross-border payment instruments built upon the principle of minimizing trade barriers and non-discriminatory access.

We welcome the use of local currencies in financial transactions between BRICS countries and their trading partners. We encourage strengthening of correspondent banking networks within BRICS and enabling settlements in local currencies in line with BRICS Cross-Border Payments Initiative (BCBPI), which is voluntary and nonbinding, and look forward to further discussions in this area, including in the BRICS Payment Task Force.

BRICS central banks don’t hold each other’s currencies as reserve assets, with limited exceptions. Just 2.3% of world central bank reserves are held in China’s RMB, up from 1.1% in 2016 but down from a peak of 2.8% in 2022. Most of them are buying gold. If the legend on US currency states, “In God We Trust,” gold says, “Trust nobody.”

Sweeping changes across the Global South would be required to make their currencies attractive reserve instruments—transparency and risk management of capital markets, the development of a local middle class, infrastructure, and education.

A great deal of this is happening in stages in many developing countries but progress is gradual and uneven. We now can foresee circumstances under which the Global South might declare independence from the dollar system. But we aren’t there yet and won’t be for years under any foreseeable circumstances.

Follow David P Goldman on X at @davidpgoldman