When Yuna turned up for her first day at work, as a clerk at a major bank, she was not expecting the tasks she would be assigned. First was to make lunch for her team. Later, she was ordered to take the hand towels from the men’s toilet home and wash them. These jobs fell to her, she was told, as the newest female member of staff.

At first she politely refused. Could the men not take their own towels home to wash, she asked her boss, but he replied incredulously: “How can you expect men to wash towels?”

“He got very angry, and I realised that if I continued to fight this, the harassment would get worse, so I started washing the towels,” Yuna says. But because she had complained, she was marked.

As she wanders through the dark alleys of her local food market, dressed in a black baseball cap, oversized jeans, and a T-shirt, she tries to disguise herself as she recounts her experience. This is a small town, and she has done something she could have been fired for. She filmed everything and reported the bank to the government, to be investigated.

What tipped her over the edge was not just the abuse, which grew steadily worse, but the lack of support from her female colleagues – those in their 20s, like her.

“It’s like this everywhere, don’t make a fuss,” they had pleaded.

South Korea may have blossomed into a cultural and technological powerhouse, but in its rapid transformation into one of the richest countries in the world, women have been left trailing. They are paid on average a third less than men, giving South Korea the worst gender pay gap of any rich country in the world. Men dominate politics and boardrooms. Currently, women hold just 5.8% of the executive positions in South Korea’s publicly listed companies. They are still expected to take on most of the housework and childcare.

To this can be added a pervasive culture of sexual harassment. The booming tech industry has contributed to an explosion of digital sex crimes, where women are filmed by tiny hidden cameras as they use the toilet or undress in changing rooms.

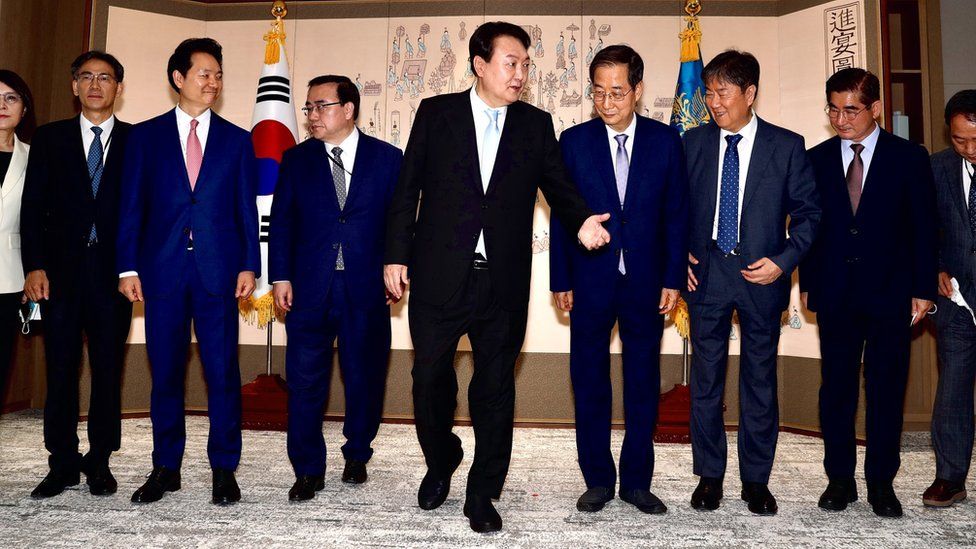

But instead of promising to fix these problems, South Korea’s new President Yoon Suk-yeol has said structural sexism is “a thing of the past”. He was propelled to power by young men who claim that attempts to reduce inequality mean they have become victims of reverse discrimination.

Upon entering office, President Yoon scrapped government gender quotas, declaring people would be hired on merit, not sex. He appointed just three women to his 19-member cabinet. He is now trying to abolish the government’s Gender Equality Ministry, which supports women and victims of sexual assault, claiming it is obsolete. More than 800 organisations have come together to protest against the closure, arguing it could have a damaging impact on women’s lives.

Hoping to fight this was 28-year-old Park Ji-hyun, a women’s rights campaigner, who, following the divisive election, was asked to lead the liberal opposition party. The party told her they needed her help to reform politics and represent young women. And so, despite having never been a politician, she agreed.

But just six months later, when we meet at a café on the outskirts of Seoul, she is no longer in post. She has had to leave her home because her address was leaked, and she was receiving so many death threats. The ones that stick with her, she says, are from the people who threaten to feed her acid or pour it in her face. It has been the hardest six months of her life, she admits, after experiencing first-hand the sexism and misogyny that pervades politics.

Park talks of her despair that she would be the only woman in meetings, and that when she spoke, nobody would respond. “They just ignored me, and I ended up shouting into a void,” she says. “When I wanted to discuss the economy or the environment, they would say: ‘You just focus on what you know – women’s issues and sex-crimes’. I realised I was a puppet in this position, being used to gather women’s votes.”

Park made her name as a student journalist, when she uncovered an online sex ring, where young teenagers were being blackmailed into filming themselves performing sexual and degrading acts. The ringleaders were sent to prison as a result of her investigation.

Online sexual assault and harassment is increasingly widespread. Last year, 11,568 cases of digital sex crimes were reported, up 82% from the year before. Many involved the use of hidden spy-cameras. Women in South Korea speak of being too scared to go to the toilet, in case they are secretly filmed and then blackmailed – or worse, the footage is released, and their lives destroyed. One compared the fear to what women in other countries must feel when walking home late at night.

But when Park pushed to investigate allegations of sexual assault within her party, she was labelled a troublemaker, and after poor local election results she was pushed aside.

As we are talking, a waitress brings over a large plate of cakes, on the house. “Thank you for fighting for us,” she says. Embarrassed, Park laughs: “This has never happened before.” During her short time in politics, she became an icon for young women who felt they’d had no-one to represent them.

In 2018, South Korea spawned Asia’s first and most successful #MeToo movement. But in its wake, a wave of anti-feminism coursed through the country, fuelled by young men who were concerned that, in their hyper-competitive society, women were gaining the upper hand. They take issue with having to complete compulsory military service, which stops them from working for up to two years. They have succeeded in turning feminism into a dirty word, with some women now embarrassed, or even afraid, to use it. But more significantly they got the president to respond to their rallying cries.

“Women have been deprived of their rights in the past, but a lot has been resolved,” says 37-year-old Lee Jun-seok, whose idea it was to close the gender equality ministry. He led the winning party into the election, helping it attract young, male votes. “Gender equality has entered a new phase. We need a new system that looks beyond feminism and focuses on the rights of all minorities.”

The ministry currently accounts for just 0.2% of the government’s budget but women say it has made a concrete difference to their lives. Since it was established more than 20 years ago it has supported the victims of hidden spy-cams and women who have been fired after getting pregnant, and secured more generous child support payments for single mothers.

Ana hasn’t been able to sleep properly since she heard about the ministry’s abolition. She credits it with saving her life. From a safe house, she recounts – in a voice so quiet it is almost inaudible – how she was failed by everyone in her life she trusted to protect her. Six years ago, she was raped by her college professor. When she called her father to tell him, he hung up the phone. She had brought the family shame, he told her.

Only after the #MeToo movement did Ana find the strength to seek help. She went to a support centre for victims of crime, but they wanted evidence before agreeing to help her. She made her case to the doctor, who told her she was delusional and denied the support.

“It was heartbreaking. I couldn’t understand how a doctor running a support centre wouldn’t help me,” she says. “I felt like I was trapped in a dark room with no exit.” A few months later she tried to kill herself.

Then the gender equality ministry stepped in. They found her a place in the safe house, provided counselling and helped Ana to pursue a successful prosecution. Her professor was sent to jail. This hasn’t stopped the flashbacks and nightmares, but – as she describes it – she has been resuscitated.

“I have received more help from this ministry than my own family, which shares my blood,” she says, holding out her hand to touch her counsellor Nam sitting beside her. “Closing it is a dangerous idea.”

The government says the ministry’s current services will continue, but be absorbed by other departments. In October the president said this would “protect women more”, though his reasoning is unclear. The plans could still be thwarted by the liberal opposition party, which holds a majority in parliament. It has voiced concern about the impact the closure will have on the progress yet to be made for women – in the workplace and at home.

South Korea’s society and job market are structured in a way that perpetuates its gender pay gap. Women struggle to re-enter the competitive workforce after leaving to have children. They often end up taking on unstable, poorly paid contract work, which can be juggled around childcare.

This was the case for 50-year-old Shin Hyung-jung, who used to work as an administrator at a school. The school expected her to work on Saturdays, but didn’t open their kindergarten then, meaning she had nowhere to leave her daughter. Her husband wouldn’t look after the baby, so she had to quit.

“He’s a typical patriarchal man, he does nothing to help,” she laughs. I ask why she is laughing. “Because it’s ridiculous, I’m dumbfounded.” For the past 20 years she has instead worked maintaining electrical items, such as water purifiers and clothes steamers, in people’s homes.

“It’s difficult lugging this around,” she says loading her equipment into a fancy elevator to service her third apartment of the morning. “I can be fired tomorrow morning and I’ll get nothing, and I have no pension. But at least I have been able to pick my daughter up from school.”

According to the latest government data, 46% of female workers are in non-permanent contract work, compared to just 30% of men. All but two of the employees on Shin’s team are women, who all started working for the company after having children. Two in their 30s joined this year, citing almost identical circumstances to the ones Shin experienced two decades ago.

Women who do not want to sacrifice their careers are now simply choosing not to have children. South Korea’s fertility rate (the average number of children a woman will have in her lifetime) has fallen to 0.81, the lowest in the world. Its population is predicted to halve by the end of the century, meaning it may not have enough people to sustain its economy and conscript into its army.

“Without solving its gender equality problem, South Korea cannot solve its birth-rate problem,” says Jeong Hyun-baek, the gender equality minister between 2017 and 2018. “The #MeToo movement did improve the culture of sexual harassment and discrimination in workplaces, but now we need structural reform to address the pay gap and the lack of opportunities for women.” She questions how the government can fix a problem it won’t acknowledge exists.

For months I asked to interview the current Gender Equality Minister, Kim Hyun-suk, but the government declined. I later approached her at an event and asked whether she agreed with the president that structural sexism in Korea no longer existed. “There needs to be more women in politics, particularly in leadership and we must work to close the pay gap, particularly between fulltime and contract workers,” she replied, without directly answering the question.

There are some signs equality in South Korea is improving. Earlier this year, long-time contract worker Shin successfully negotiated a wage increase through her union, after a 10-year pay freeze. It was the first time a group of part-time contract workers in her industry had won such a battle.

“I do feel like society is slowly changing, and my daughter will have a better future,” she says. “I’ve given up on my husband, but I haven’t given up on my country.”

Then last month, Yuna, the bank clerk, got a call from the government. Their investigation concluded the bank had broken the law, by committing sexual harassment and discrimination. It has been ordered to pay a fine and she is being transferred to a different branch.

The thought of returning to work is making her ill, she said when we caught up over the phone, but she is happy she reported the bank. Since doing so, other female employees have reached out with similar stories.

“I do think over the past ten years equality has improved, but this is a small city, and things are not changing here, the president is not looking deep enough”, she said, worried the recent gains could be undone.

“If this ministry disappears, what we have built could collapse”.

*Yuna’s name has been changed to protect her

Additional reporting by Won-jung Bae and Hosu Lee

BBC 100 Women names 100 inspiring and influential women around the world every year. Follow BBC 100 Women on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter. Join the conversation using #BBC100Women.

-

-

23 September

-

-

-

16 June 2021

-

-

-

10 August 2021

-