According to calculations by 132 domestically listed developers by Chinese data provider Wind, combined sales revenue fell by 8.3 per cent last year – the first since 2005 – while their debt ratio was 78.99 per cent in 2022, only slightly lower than 79.03 per cent in 2019.

The data, though, did not include Evergrande and other Hong Kong-listed firms.

Their return on equities registered the first decline on record of 3.78 per cent, and the domestically listed developers reported a combined loss of 66 billion yuan – also the first loss since the data became available.

They also had a new cash outflow of 285.6 billion yuan from their fundraising activities – a sign that the sector is struggling to seek external funding from banks, investments or bonds.

But the problems have not significantly spilled over into the financial system.

The non-performing loan ratio in the property sector was 1.4 per cent when it was last released in 2020, the highest since 2010 but lower than 9.2 per cent in 2005 and 3.35 per cent in 2008, according to data provided by the National Financial Regulatory Administration.

China, though, has not updated the non-performing loan ratio for the property sector since 2020.

But the overall non-performing loan ratio for commercial banks was just 1.62 per cent by the end of June, lower than 1.81 per cent four years ago.

“State ownership provides Chinese banks with a degree of protection against problems elsewhere in the financial system and there are currently few signs of any strains in the interbank market,” said Julian Evans-Pritchard, chief China economist at Capital Economics.

“But even if a wider financial crisis is avoided, shadow bank failures are likely to result in tighter credit conditions for subprime borrowers.”

Zhongzhi Enterprise Group, one of the country’s largest private wealth managers, have reportedly failed to repay some maturing products under more than 1 trillion yuan of assets that the company manages.

In late July, Zhongzhi reportedly hired professional services firm KPMG to conduct an audit of its balance sheet.

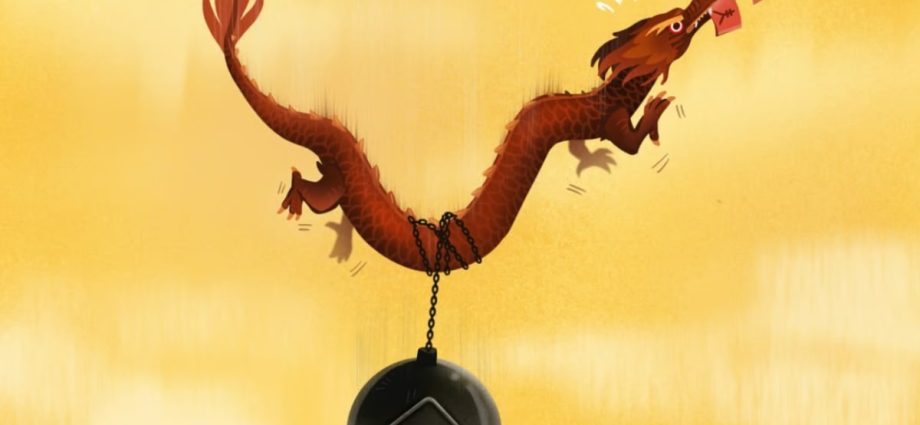

“The next few weeks are crucial, as the clock is ticking for some of the major developers,” said Larry Hu, chief China economist at Macquarie Capital, who attributed the ongoing property woes to a downward spiral between confidence and sales.

“Now the game changer is a package of policy measures, which is strong enough to turn around the market expectation and pull the housing market out of the current downward spiral.”

The one-way bet on property is now waning as the myth that China’s property prices will keep rising has been broken.

The value of property sales in the first seven months of the year fell by 1.5 per cent to 7.05 trillion yuan, while the floor space sold dropped by 6.5 per cent from a year earlier to 665.6 million square metres, government data showed.

After China’s Politburo, headed by President Xi, removed the sentence that “houses are for living in, not for speculation” in July, markets have been expecting further policy relaxation.

In June, the central bank extended 200 billion yuan of relending quotas to ensure completion of unfinished property units and allow commercial banks to roll over maturing loans after the Evergrande crisis, extending the policies until the end of next year.

Different from Western bailouts, Beijing tends to allow state-owned players and banks to help absorb troubled companies.

In the case of Evergrande, authorities dispatched special teams to the company to ensure the delivery of property units, the management of debt repayment and to ensure overall social stability.

In a de-risking conference on Friday, China’s central bank, as well as its banking and securities regulators, pledged to optimise credit policies and enrich tools to defuse local debt risk.

“We must firmly defend the bottom line of preventing systemic risk,” they said.

Bridgewater founder Ray Dalio said that China is better positioned than many other countries because debts are largely in yuan and they are largely owed to domestic citizens and institutions.

“There is an obvious need for a big debt restructuring of the sort that Zhu Rongji engineered in the late 1990s, just much bigger,” he said on Friday, referring to Zhu’s move to set up four national asset management companies to split bad loans from state banks.

The legendary fund manager’s “beautiful deleveraging” theory, which balances deflationary defaults and restructurings with debt monetisation to spread out the burden, has attracted significant attention from high-ranking Chinese officials in the past five years.

“If the government has tools to change the dire economic situation then they either aren’t using them or they are not working,” added Howie.

“The best scenario is muddling through where the government manages a slew of chronic economic problems and hopes they don’t become acute ones which could have significant shocks or cause panic, i.e. allowing localised bank failures but ensuring the state banks in big cities don’t see [bank] runs.”

A likely outcome, according to Magnus, is that the real estate waves are likely to last a long time and the only viable solution is by allocating the costs of the crisis to someone – government, banks or homebuyers.

“In China’s case, this might mean the resocialisation of much of the housing sector,” he said.

“I don’t think anyone should think there’s a free lunch out there or that this won’t be a painful experience.”

This article was first published on SCMP.