India should dismantle its large conglomerates to increase competition and reduce their ability to charge higher prices, former Reserve Bank of India deputy governor Viral Acharya has argued in a new paper for Brookings Institution, an American research group.

According to Mr Acharya, who is now a professor of economics at NYU Stern, “industrial concentration” – which refers to the extent to which a smaller number of firms account for total production in a country – fell sharply in India after 1991 when the country opened up its economy and state-owned monopolies began giving away their market share to private enterprises. But after 2015, it began rising again.

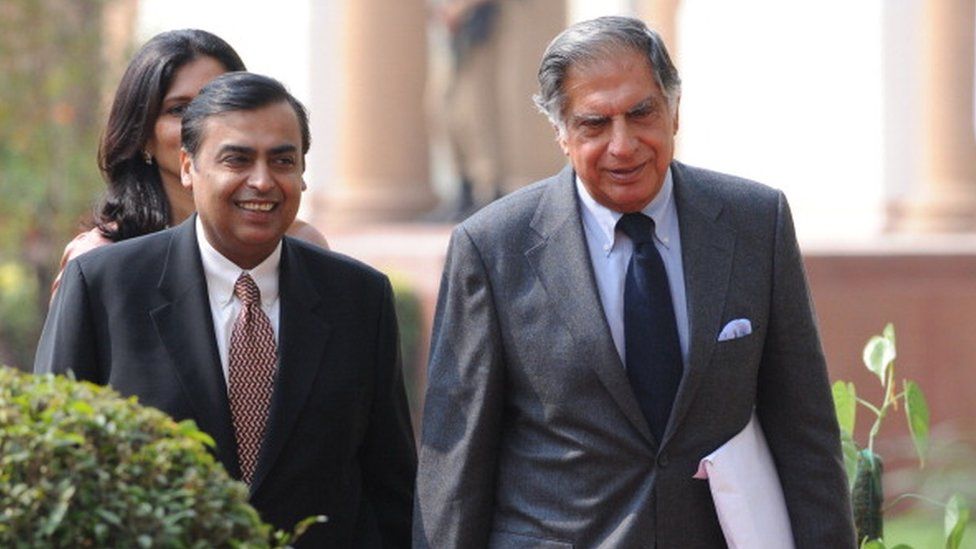

The share of India’s “big five” conglomerates – the Reliance Group, Adani Group, Tata Group, Aditya Birla Group and Bharti Airtel – in total assets of non-financial sectors rose from 10% in 1991 to nearly 18% in 2021.

They “grew not just at the expense of the smallest firms, but also of the next largest firms”, says Mr Acharya, because the share in total assets of the next five business groups halved from 18% to 9% during this period.

There could have been many drivers of this, according to Mr Acharya – their ability to acquire large distressed companies, a growing appetite for mergers and acquisitions, and India’s conscious industrial policy of creating “national champions via preferential allocation of projects and in some cases regulatory agencies turning a blind eye to predatory pricing”.

The trend raises several concerns, according to the former deputy governor. These include “the risk of crony capitalism, i.e., political connections and inefficient project allocations, related party transactions within their byzantine corporate organisation charts”, taking on excess debt to fund their expansion and preventing competitors from entering the market.

Excess leverage was, in fact, one of the many red flags that US-based short seller Hindenburg Research had also raised against the Adani Group recently. The report led to billions of dollars being wiped from the stock market.

In other countries this has had far graver spillover effects in the past.

“National champions can easily become overleveraged and collapse, severely damaging the overall economy, as has occurred in other Asian countries, most spectacularly Indonesia in 1998,” Josh Felman, former India head of the International Monetary Fund, told the BBC.

In a February column for Project Syndicate, the economist Nouriel Roubini had also expressed concerns about India’s economic model of giving a few “national champions” or “large private oligopolistic conglomerates” control over significant parts of the economy.

“These conglomerates have been able to capture policymaking to benefit themselves,” wrote Mr Roubini. The phenomenon was stifling innovation and disallowing entry of start-ups and other domestic entrants in key industries, he said.

India’s policy of creating “national champions” is similar to those adopted by China, Indonesia and particularly South Korea in the 1990s, where a group of mostly family-run business conglomerates – called chaebols, of which smartphone giant Samsung is the most prominent example – dominated its economy.

But unlike India, these countries “did not protect their conglomerates with sky-high tariffs”, says Mr Acharya. India, however, has been becoming more protectionist in order to “insulate domestic industries and conglomerates from global competition”, Mr Roubini wrote.

All of this has major implications on India’s attempts to become the next factory of the world.

According to both Mr Acharya and Mr Roubini, India needs to reduce tariffs to become more globally competitive and take advantage of the “China plus one” trend where supply chains are moving away from mainland China into geographies like India and Vietnam.

India’s industrial concentration could also have domestic consequences – the rising market power of the “big five” may be one of the contributors to persistently high core inflation, or the rise in the price of goods and services barring food and energy.

“While a deeper and fuller inquiry is warranted, we find that there is a potentially causal link from market power to markups,” writes Mr Acharya, adding that these companies are able to “exert extraordinary pricing power and capture economic rents relative to other firms in the industry”.

But other economists told the BBC that they are sceptical of this correlation.

“If a ‘big five’ firm enters a new sector, the group may become bigger, but competition in that specific sector may increase and prices might actually fall. A most spectacular example of this dynamic occurred when Reliance decided to start [telecom company] Jio: telecoms prices crashed,” says Mr Felman.

Madan Sabnavis, chief economist at Bank of Baroda, says there isn’t “enough evidence” to support this thesis.

According to him, even in markets dominated by a small number of firms, such as airlines – where most of these conglomerates do not have a presence – prices have consistently been high.

He adds that the sectors that feed into core inflation at the consumer level – recreation, education, health, household goods, consumer care – don’t have the presence of the big five either.

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC:

Related Topics

-

-

6 October 2022

-