When Muralikrishnan Chinnadurai observed something strange while watching a video of a Tamil-language function in the UK in November of last year.

A person introduced as Duwaraka, child of Velupillai Prabhakaran, the Tamil Tiger violent chief, was giving a speech.

Duwaraka had passed away in an attack in 2009, in the Sri Lankan legal war’s final days, more than a decade before. The next- 23- yr- old’s body was not found.

And now she was, a evidently middle-aged woman, exhorting Tamil people from all over the world to continue their political fight for their freedom.

Mr. Chinnadurai, a fact-checker in Tamil Nadu’s southern Indian state, closely observed the video, noticed flaws in it, and quickly determined that the figure was a result of artificial intelligence ( AI ).

The potential difficulties were immediately apparent to Mr Chinnadurai:” This is an emotive problem in the state] Tamil Nadu] and with votes around the corner, the propaganda was immediately spread”.

As India prepares to conduct elections, it is impossible to avoid the abundance of AI-generated information being produced, from campaign video to personalized sound messages in various Indian language, and even automated calling made to voters in a candidate’s words.

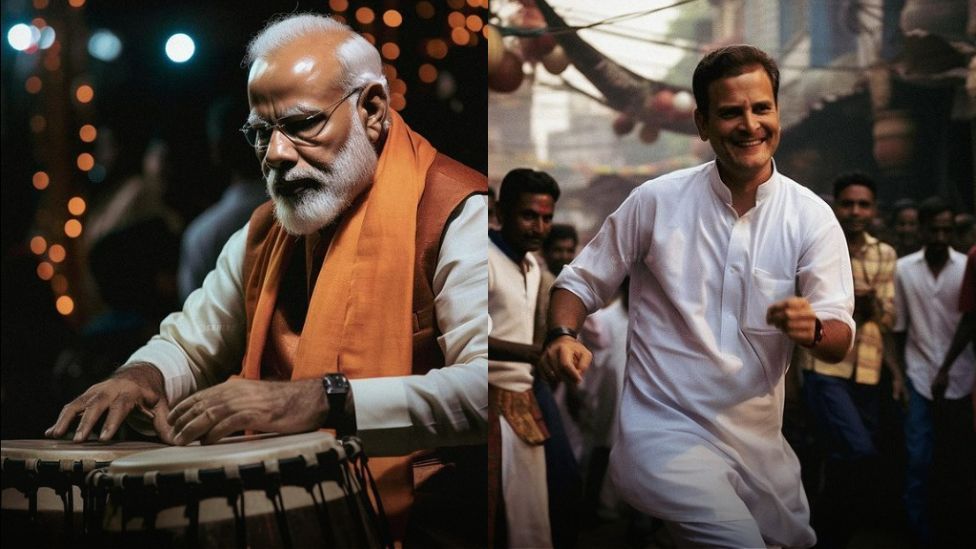

Content developers like Shahid Sheikh have also enjoyed using AI to depict American officials in new characters, including those who dance, play music, and dance.

However, as the tools become more complex, experts are concerned about how it might affect how false information is made to seem real.

” Speculations have always been a part of campaigning. ] But ] in the age of social media, it can spread like wildfire”, says SY Qureshi, the country’s former chief election commissioner.

It” is really ignite the nation.”

The social events of India are not the first to profit from new advances in AI. Imran Khan, a imprisoned politician, was able to speak at a protest just over the border in Pakistan.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has now made the most of the recently developed technologies when speaking to an audience in Hindi, which was done by using the government-created AI application Bhashini, to real-time translate Tamil into Tamil.

However, it can also be used to change terms and information.

Ranveer Singh and Aamir Khan ran for the opposition’s Congress party in two popular videos next month. Both filed authorities problems saying these were deepfakes, made without their acceptance.

Then, on April 29, Prime Minister Modi expressed concern that some of his party’s senior officials, including him, might be using AI to obstruct remarks.

In connection with a doctored video of Home Minister Amit Shah, police made two arrests the following day, one each from the Aam Aadmi Party ( AAP ) and the Congress party.

Similar allegations have also been made by Mr. Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party ( BJP) members in the nation.

The issue is that, despite the detention, there is n’t a comprehensive legislation in place, experts claim.

Which means “if you’re caught doing anything wrong, then there might be a hit on your wrist at best”, according to Srinivas Kodali, a data and surveillance scholar.

Creators told the BBC they have to depend on private ethics to determine the kind of job they choose to do or not do in the lack of regulation.

The BBC learned that officials had requested pornographic images and the morphing of their adversaries ‘ films and audios to harm their standing in the process.

According to Divyendra Singh Jadoun,” I again asked to make an initial look like a deepfake because the initial video, if shared frequently, would make the politician look bad.”

So his team wanted to pass off as the original with a deep fake.

Mr. Jadoun, the founder of The Indian Deepfaker ( TID), a platform that helped people use open-source AI to produce campaign materials for Indian politicians, insists on including disclaimers on any claims he makes to make it clear that they are not authentic.

But it is still hard to control.

In the eastern state of West Bengal, Mr. Sheikh’s work has been shared on social media by politicians or political parties without their permission or credit.

One politician claims that he used an image of Mr. Modi that I had created without any context and without mentioning that it was created using AI.

And anyone can now create a deepfake so quickly.

What used to take us seven or eight days to create can now be completed in three minutes, says Mr. Jadoun. ” You just need to have a computer”.

Indeed, the BBC had first-hand experience with how simple it is to make a fake phone call between me and the former US president.

This video can not be played

JavaScript must be enabled in your browser to play this video.

India had initially stated it was n’t considering a law for AI despite the risks. This March, however, it sprung into action after a furore over Google’s Gemini chatbot response to a query asking:” Is Modi a fascist”?

Rajeev Chandrasekhar, the country’s junior information technology minister, said it had violated the country’s IT laws.

Since then, the Indian government has asked tech companies to get its explicit permission before publicly launching “unreliable” or” under- tested” generative AI models or tools. Additionally, it has cautioned against responses by these tools that “violate the integrity of the electoral process.”

However, it is n’t enough: fact-checkers claim keeping up with debunking such content is difficult, especially during the elections when misinformation is at its highest.

” Information travels at the speed of 100km per hour”, says Mr Chinnadurai, who runs a media watchdog in Tamil Nadu. The debunked information that we distribute travels at 20 kilometers per hour.

And these fakes are even getting their way into the news, according to Mr. Kodali. Despite this,” the election commission is publicly silent on AI.”

” There are no rules at large”, Mr Kodali says. ” They’re letting the tech industry self- regulate instead of coming up with actual regulations”.

There is n’t a foolproof solution in sight, experts say.

” But]for now ] if action is taken against people forwarding fakes, it might scare others against sharing unverified information”, says Mr Qureshi.